People accused of possessing, dealing or using drugs are being excluded from or prohibited from physically entering Old Town/Chinatown. For the first time in Portland’s history, they are also being excluded from downtown Portland and the Lloyd District.

Since the program began on June 1, Portland’s new drug impact area policy has already excluded 30 people from entering those areas for at least one year, and up to three.

Earlier this year, business owners, residents and other constituencies of Old Town decried the sharp and noticeable uptick of drug use in their neighborhood, and begged the city to take action.

“It’s a notoriously bad place for drugs,” says Bill Prince, the Multnomah County District Attorney prosecuting the crimes.

That was also the hope for the “Drug Free Zones,” which excluded people from the Old Town area until the program ended in 2007. Then Mayor Tom Potter allowed Drug Free Zones to sunset because he had concerns that the program, which largely excluded African Americans, was discriminatory.

A police officer, under the old Drug Free Zone, would stop someone suspected of using, possessing or dealing drugs. If an officer had enough evidence to prove that the person indeed had drugs, individuals were excluded from the area on the spot, for 90 days. It did not go on the individual’s criminal record, and there was little recourse.

The new drug impact areas are starkly different than the old Drug Free Zone. Now the process is a multi-step process involving the district attorney’s office, the court system and parole and probation.

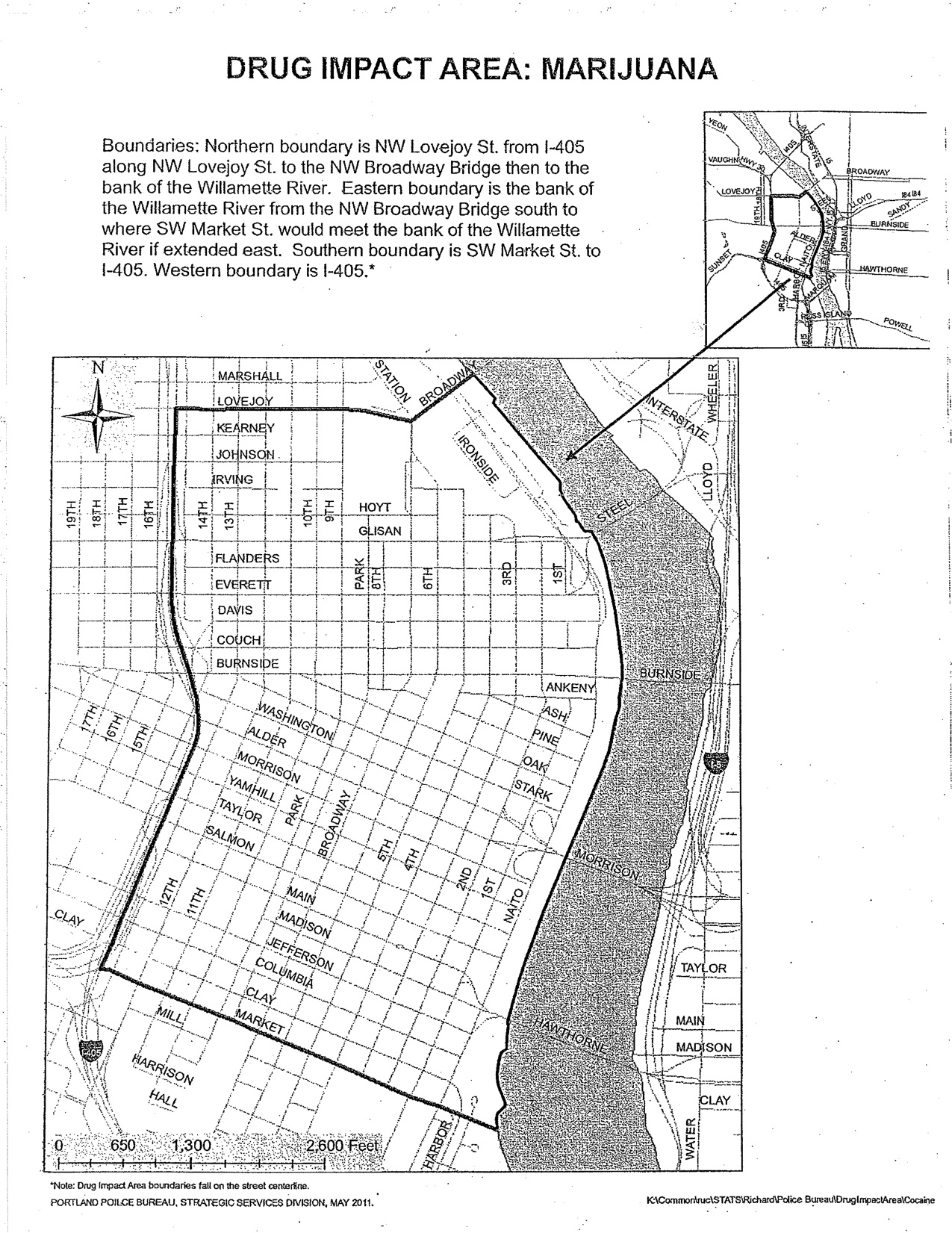

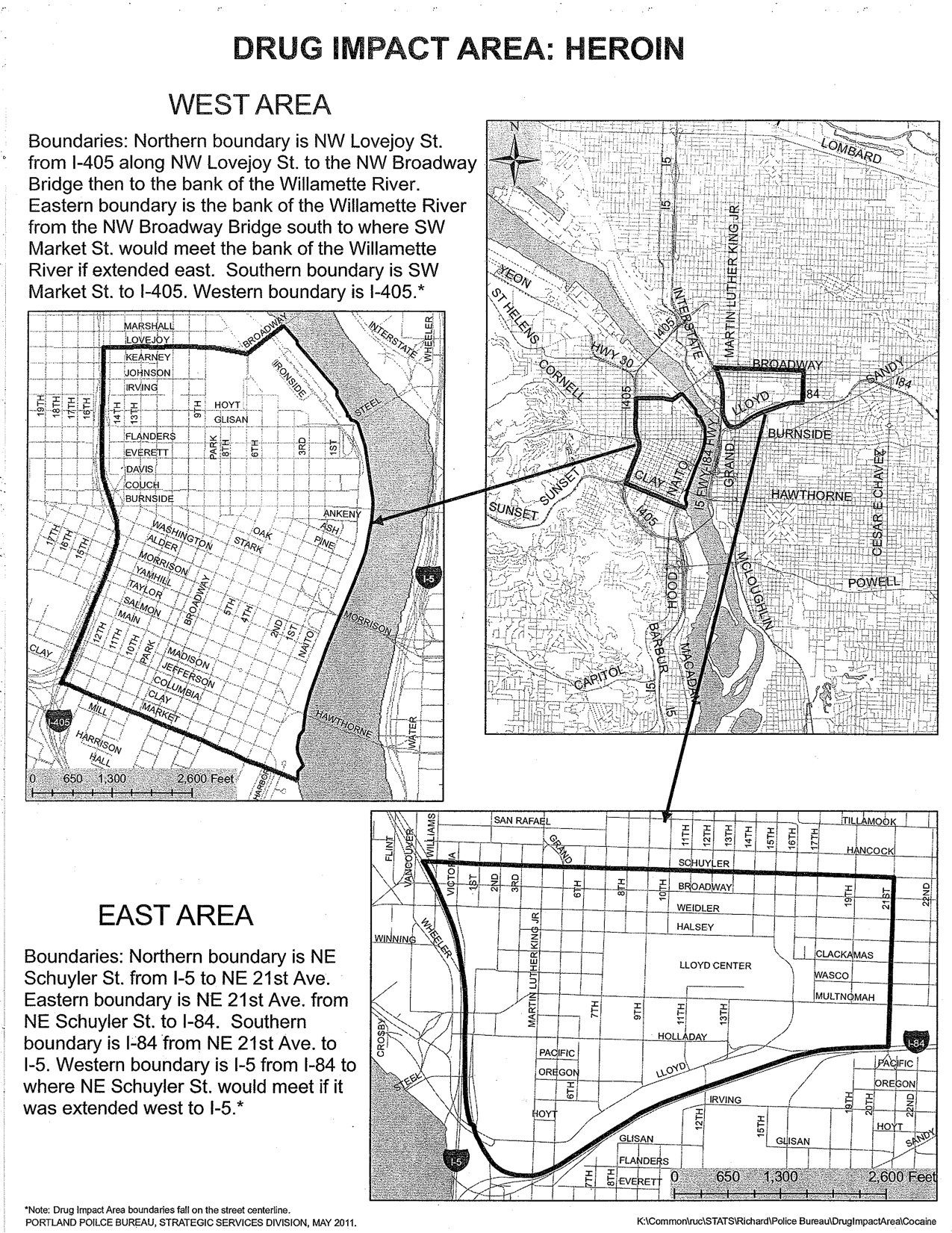

Individual’s are now arrested by a police officer if they are found to be in possession of a drug, dealing the drug, or using it. The drug impact areas are targeting two specific drugs: heroin and cocaine, along with marijuana.

The reason why those specific drugs were chosen, Prince says, is that arrest data kept by the Portland Police Bureau shows that the highest number of arrests in the areas of Portland now in the drug impact area come from those drugs. “It’s not arbitrary,” Prince says.

A deputy district attorney reviews the arresting officer’s report and decides if the case is prosecutable. If it is, the defendant gets an attorney and decides if he wants to take the case to trial. If he does not, then he enters into a plea agreement with the district attorney’s office.

The person is then put on probation. Any person convicted of a drug crime is put on probation, meaning that while the person is not in jail, they will continue to be under the supervision of a judge or a probation officer.

There can be numerous conditions of a person’s probation: that he or she attend Alcohol Anonymous (AA) meetings, go to drug treatment, and stay away from certain people or places that may aggravate those circumstances. The purpose of placing conditions on someone’s probation is that he or she does not act in a way that may lead to commit another crime.

When Portland’s City Council passed the ordinance creating the new drug impact areas in April, they also essentially created a new condition of probation: that a person be disallowed from entering Old Town, parts of downtown, and the Lloyd District. And by making it a condition of probation, the judge presiding over the hearing signs an order that the person not to enter those areas.

And whereas under the Drug Free Zone someone would have been excluded for 90 days, people are now excluded for between one year and three years.

The length of exclusion depends on a couple of factors, Prince says. One is the crime the individual is convicted of and whether it’s a misdemeanor drug offense or a felony drug offense. The judge also has discretion in determining how long a person should be excluded.

There are exceptions: if a person is going into Old Town, downtown or the Lloyd Center to seek social services, educational opportunities and/or work. If a person is found in the geographic area of the drug impact area and not for one of the excepted reasons, he or she, can be found in violation of their probation. Individuals probation can then be lengthened, and could face jailtime along with other possible consequences.

An individual is also screened by the Service Coordination Team (SCT), a controversial group of police officers and service providers who work in partnership targeting repeat drug offenders.

The program is more structured than the old Drug Free Zones, Prince says. “You wouldn’t have gone to trial,” he says, emphasizing that the process of excluding someone is now more transparent.

“The program is well thought out. It is based on the data,” Prince says.

He also says that the concerns social service providers and advocates had about civil liberties and race discrimination surrounding the Drug Free Zones have been addressed.

But neither the city, the Portland Police Bureau, nor the district attorney’s office are tracking race, gender, or other demographic information.

Prince says data is being compiled on the number of arrests made, how many people are being excluded, and how many people are going to prison versus simply being put on probation. A prison sentence may be likely if the individual is convicted of a felony, or if individuals have warrants out for their arrest. But he says there are no intentions of tracking demographic statistics.

“My feeling is that we have it all available,” in the police reports, he says.

Amy Ruiz, the spokesperson for Mayor Sam Adams, says the district attorney will seek exclusions for every drug case, regardless of race. And the City Council will get reports from the District Attorney’s office every 90 days with information on how the program is working, including the locations of prosecuted offenses, probation violations, the number of people excluded, and their demographic characteristics. She did not say if race was one of those specific characteristics.

Even though the program is less than two months old, advocates already have other, numerous concerns that the program may violate people’s constitutional rights.

Chris O’Connor, a public defender with Metropolitan Public Defender, says that people have a right to travel, associate with others, and similar rights under the 14th amendment. “And how could a person prove that they are in a particular area to, for example, seek social services, if they do not have written documentation of an appointment? That has not yet been tested”.

The person, O’Connor says, could be stopped by a police officer, and the officer could possibly assume that the person has been excluded. “There could be illegal stops and seizures,” O’Connor says.

Also of concern is that anyone in Multnomah County can be excluded from the drug impact areas, regardless of where an individual is arrested. For example, if someone were arrested for heroin possession in east Multnomah County, or arrested for cocaine dealing in far southwest Portland, that person could still be excluded from Old Town and downtown Portland, whether they frequent that area or not.

“The District Attorney will seek stay-away orders as a condition of probation for all people who are convicted of a drug offense in Multnomah County,” says David Woboril, an assistant city attorney. “It will be up to the judges to determine how they want to handle this new type of probation violation.”

O’Connor thinks that makes no sense. “There is no nexus with the crime,” and the area they are being excluded from, he says. “You kick them out of a different part of the county,” he says.

Ruiz says that because the drug impact area program has been folded into the court system, an individual’s Constitutional rights are safeguarded. “Judges are issuing the stay away orders as part of sentencing,” Ruiz told Street Roots via email. “In that context, judges could do much more to impact a person’s ability to travel and associate, by putting someone in jail. Also, keep in mind that the stay away orders contain numerous exceptions that allow a person to enter or pass through an IDIA to meet critical needs.”

And is the drug impact area a program with a paperless policy? Street Roots made public records requests for any written guidelines or protocol for the Drug Impact Areas from the Portland Police Bureau and the City of Portland. We were told none existed to date.

By folding the drug impact areas into Multnomah County’s existing parole program, there would seem to be no need for a policy outlining what the program is, how it works, the process, the standards upon which someone is excluded, etc.

Other policies created by city ordnance that involve the police have such policies. One example is Portland’s camping ordinance, which makes it illegal to camp on public property. The Portland Police Bureau has what are called “standard operating procedures” that detail what the police officer can and cannot do when they find someone camping underneath a bridge.

No such procedures exist for the drug impact policy. “There is no clear guidance in the ordinance. They’ve learned a lesson from the Drug Free Zone,” O’Connor says. “It’s a smart move if you want to avoid outside critics from seeing the data.”

During the city council’s April discussion before creating the drug impact areas, Mayor Sam Adams assured critics that there would be opportunity for concerned parties to reconvene and discuss how the program was working, give input, and make changes.

“The Mayor’s office assured those of us who were concerned that there was going to be opportunity for policy” discussions, input and feedback,” says Chani Geigle-Teller, community organizer with Sisters Of The Road. “That hasn’t happened. The community has had no input.”

Ruiz says that the mayor’s staff will check in with neighborhood and community organizations this fall.

The ACLU of Oregon told Street Roots this week that the organization is starting to monitor the program’s implementation.

Read the SR editorial on Drug Impact Area's here.