Anne Frank and Eva Schloss, both born in 1929, had known each other for a long time before they became stepsisters. In fact, when they did become stepsisters in 1953, Anne was no longer alive. By the age of 15, both young girls had survived Auschwitz. However, just before the end of the war, Anne Frank and her sister Margot were transported to Bergen-Belsen. Anne and Margot died there on an unknown day in March 1945, from typhus, hunger, cold, violence and despair.

Now aged 85, Eva Schloss says she survived Auschwitz through “luck, luck and more luck.” Soviet troops freed her and a few other survivors (including her mother and Anne Frank’s father) on Jan. 27, 1945. Eva found her way back home to Amsterdam through the Ukraine, the Black Sea and the Mediterranean sea.

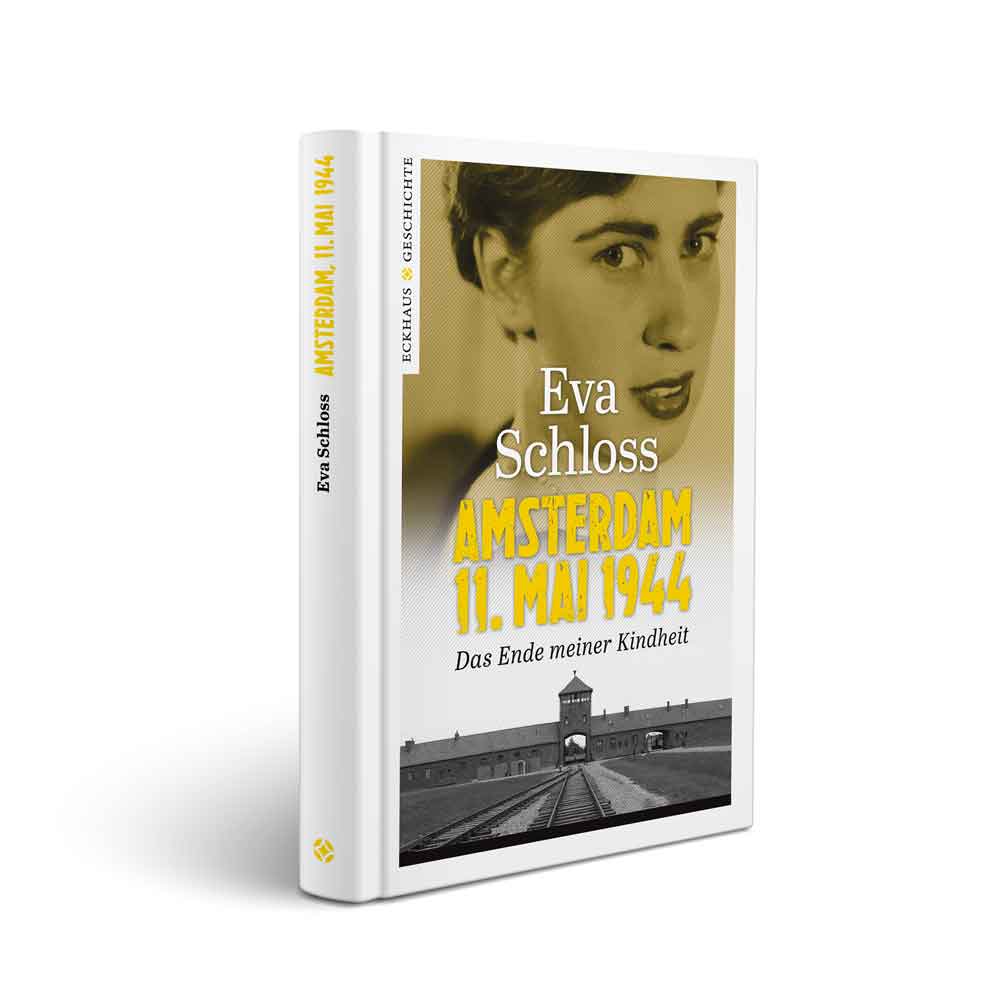

She’s written about her experiences in a new book, “Amsterdam 11. Mai 1944: Das Ende meiner Kindheit” (Amsterdam May 11, 1944: The end of my childhood.) On April 16, the United States marks Holocaust Day of Remembrance, or Yom HaShoah.

In 1953, Otto Frank married Eva’s mother. The story of the two families can serve to represent the deaths of millions of Jews during the Holocaust, and the survival of few. It also highlights a fact that is often supressed: in the last year before British troops liberated the Bergen-Belsen camp on April 15, 1945, conditions there were as atrocious as they were at Auschwitz. From 1943 to 1945, 55,000 Jews, Romany people and prisoners of war were tormented to death there. Another 15,000 people died, exhausted, after being freed.

Anne Frank is known all over the world for her diary, and for the untiring efforts of her father, Otto Frank. He was the only member of the family to survive Auschwitz. His fearless, non-Jewish colleague Miep Gies, who kept the Frank family alive for two years in the Amsterdam secret annex under the toughest circumstances, gave the diary to Otto when he returned. After the family’s arrest, she found it in the back rooms in Prinsengracht and carefully stored it away.

In summer 1945, Otto Frank read about the thoughts, fears and hopes of his murdered daughter and was shocked. “That’s not how I knew her,” he said.

Anne’s diary, originally in Dutch, has been translated into 70 languages, has sold 30 million copies and was declared part of the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2009. There are Anne Frank memorial sites in Amsterdam, New York, Frankfurt, Berlin and Tokyo. Upon his death, Otto Frank bequeathed all proceeds from the diary’s sensational sales to the Anne Frank Fonds in Basel. He kept the memory of his family’s fate alive to help stop the horror of the Holocaust from ever happening again.

Eva Schloss is not as well known as Anne Frank. However, she can report on what happened after Anne’s diary, which stopped on Aug. 1, 1944. Eva Schloss describes the events in detail today: in remembrance and as a reminder. Like Anne, she was arrested in the secret annex, brought to the Nazi Westerbork transit camp and, from there, transported to Auschwitz in a livestock wagon on one of the notorious Thursday transports. Like Anne, Eva survived the selection on the ramp: She was not sent straight to the gas chambers like almost a million others sent to Auschwitz, but was selected for “extermination through labor.”

Eva Schloss became Anne’s stepsister in 1953, when Anne’s father married Eva’s mother. They knew one another from their time in exile in Amsterdam, and met again on the arduous return journey from the liberated Auschwitz.

They felt bound to one another by the horror they had experienced and survived at the death camp, each having lost most of her family. Eva Schloss emphasizes: “Life was very hard on those who survived. It was extremely hard after the war if you tried to live a normal life again.”

For many years, Europe was on the verge of chaos and sympathy for the suffering the Jews endured was rare, let alone any financial or psychological help. Eva Schloss was severely depressed for years.

She received support from her mother and Otto Frank. Until they went into hiding in 1942, he had been an avid photographer who carried his Leica with him wherever he went. This is why there are so many portraits of Anne and Margot as children and adolescents. When they went into hiding, his series of family portraits came to an abrupt end. Where would Otto Frank have gone to develop these photos of the persecuted? Holland helped the Jews to a certain extent, which formed a significant contrast to the hatred and violence they met with from the German and Austrian populations. Yet even in Holland, the danger of betrayal was always there.

After he returned from Auschwitz and learned that his family and friends had all been killed, Otto Frank gave up his photography: “I no longer have a family. I do not want to take any more photographs.”

Yet he saw the sorrow of his stepdaughter Eva, and gave her his Leica. Very slowly, she learned about photography. Her lessons from Otto gave her the courage to face life again, even if she was never able to overcome the loss of her father and her brother Heinz, who were killed just before the end of the war on a death march from Auschwitz to the Austrian Mauthausen concentration camp.

In later years, Eva often asked herself why she survived. She even escaped the death marches to the concentration camps in the west, which Hitler ordered in the final weeks of the war to clear out the extermination camps and cover up the atrocities carried out there. However, after the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp, Russian soldiers brought Eva to safety far away in the east. These soldiers fed and protected the few survivors.

In late 1944, Anne and Margot were transported again, from Auschwitz to the Bergen-Belsen Nazi camp in Lower Saxony. Together with tens of thousands of Jews, they were detained there in the winter months before the end of the war. There was hardly any food, no clean water, no toilets, no warm clothes, and no medical care.

Very few people survived the “inferno of Bergen-Belsen” but Hannah Pick-Goslar is among them. She describes how, in early March 1945, she tried to slip her friend Anne a small Red Cross package. Anne was sick with typhus, but even that small gift was snatched away from her.

Janny Brandes-Brilleslijper, who died in 2003 at 86, was one of the last people to see Anne alive. She recalled a bitterly cold day in early March 1945 when she saw Anne, emaciated, with her bones protruding, and wearing only thin rags. She had thrown away the camp clothing because it was full of parasites that were eating into her skin.

In the 1950s, the site of the former Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was made a memorial site at the insistence of the survivors. Later, the whole compound fell into decay. It was only in the '80s that Germany began commemorating the events as was worthy. Now, a sleek, distinct memorial relates the history of the compound. Fates are brought to life, detainees are named and their stories told, and the injustice is being termed as such. A research project titled “Book of Remembrance” has so far identified the names of around 55,000 detainees, with the dates of their births and deaths. This is not even half of all those imprisoned or killed at Bergen-Belsen.

The Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education exhibit on Anne Frank runs through April 14, 2015.

On April 16, 2015, The Jewish Federation of Greater Portland and Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education are hosting a program commemorating Yom HaShoah-The Day of Remembrance titled “Unto Every Person There is a Name.” The event begins at 10 a.m. in Pioneer Courthouse Square with prayers, poems and candle lighting. The program ends at 6 p.m. The ceremony includes the reading of approximately 5,000 names of those who perished in the Holocaust.

Translated from German to English by Melanie Vogt. Courtesy of INSP News Service www.street-papers.org / Asphalt magazine