In June 1897, 20 African American infantry men rode their bicycles from Missoula, Mont., to St. Louis, Mo., a 1,900-mile trip that took 41 days.

Those men made up the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, the first military regiment in United States’ history that was equipped with – and traveled by – bicycles. The Bicycle Corps was commissioned in 1892 by the Army at a time when bicycles were highly popular. The corps’ purpose was to travel throughout the country, collecting geographic and topographical information and document road conditions, sources of supplies, and other information that could be useful to the military.

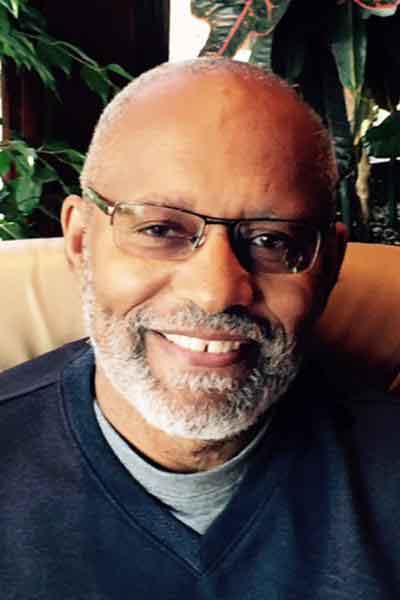

The Bicycle Corps and the men who were a part of it are the subject of “Ole Freedom,” a historical novel written by Portland author Pferron Doss. Doss taught the history of the bicycle corps in the black studies department at the University of Montana and in 1974 led a re-enactment of the bicycle trip from Missoula to St. Louis. Doss self-published the book this year, drawing the title from an old spiritual song.

Doss spoke with Street Roots about the corps, his book and race relations.

Amanda Waldroupe: How did you first learn about the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, and what was it about the corps that captivated you?

Pferron Doss: When I attended the University of Montana from 1969 to 1973, there weren’t that many blacks at the university. As a member of Black Student Union, we used to go across the state talking about the black experience. Oftentimes, we would get comments like, “You don’t understand; we’ve never seen any colored people.” Frankly, it ticked us all off. I started going through the library and doing research about blacks in Montana, all the way from the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the last legal execution of an African-American in 1954. The archivist showed me a picture of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps. I thought it was a fake picture. He said, no, they came here in 1888. I said, “What?!” That started my love affair with the 25th Infantry.

In 1974, I had a chance to interview the sole survivor of the Infantry, Dorsie Willis. Then I had a dream. I dreamt the entire book minus the ending. So I started to write. I was pretty addicted to the book. Wherever I left off in the writing, I had a dream about what would happen next. I got it written and copyrighted. But many rejects. So I put it aside for 25-plus years.

A.W.: When you were a college student talking about the black experience in Montana, what would you talk to people about? What were the experiences like?

P.D.: Well, this will show you how ignorant people can be. People wanted to know what we ate. Why we grew our hair like Afros. People would come up to us and rub our skin and touch our hair. They wanted to know why we were in Montana and what we were doing in school and if we were getting a free ride. They would say, “We’ve never seen any blacks except on TV,” and they thought that we were pretty violent. “Well,” we would say, “wait a minute. Let’s talk about that. The indigenous minority in Montana are Native Americans. Think about how you treat the Native Americans, historically and even currently, and you’ll understand some of the stuff that we have gone through.”

A.W.: That must have been such an alienating experience.

P.D.: Yes, it was. We’d gotten in a couple scuffles over race, and I was even shot at one night.

A.W.: The Bicycle Corps was well-known and respected, right?

P.D.: The 25th went to Montana in 1888. They were garrisoned at Fort Missoula, and they did create an atmosphere where they were appreciated by the local community. When they left in 1898 to go to the Spanish-American War, it was Easter Sunday. Most Sunday churches delayed services so people could go see them off. When the 25th was in its infancy, before World War I, they were pretty respected in the state of Montana. They were at the (site of the) Wounded Knee Massacre the following day; they did the original surveying of the Battle of Little Bighorn, where Custer lost. They were responsible for quelling the mine wars in Idaho. Their involvement in societal as well as military ventures was pretty well known. But that history has died off.

A.W.: Why do you think that is?

P.D.: It’s no different than American history for all minorities. It’s in vogue, but it doesn’t stay in vogue because if you’re trying to deny equal citizen status to everybody or deny it to African-Americans specifically, you don’t talk about the positive stuff. When I went to school, the history books were 350 pages long, and there was one chapter about African-Americans. There was slavery and then there was freedom. There was never any talk about the contributions that were made.

A.W.: The men in the Bicycle Corps also played an important role during the Spanish-American War – even though they weren’t on bikes.

P.D.: There were members of the Bicycle Corps that were part of the 25th Infantry Regiment. They did not have bicycles; they were just regular fighting soldiers. Everybody grew up knowing that Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders are the ones who charged San Juan Hill. If you look at military records, as I did, you see that Buffalo Soldiers (a nickname for the regiments of black soldiers at the time) broke into the blockhouse and captured the flag. They were not credited for it because of the times. The government was not going to give credit for such an event to black soldiers.

A.W.: There is something very radical and unusual – even phenomenal – about the idea of a group of black men riding bikes halfway across the country, especially the Midwest, in the late 1800s. How do you think the Bicycle Corps was able to even exist?

P.D.: Well, towards the end of the 1800s, Asiatic as well as European countries were beginning to use the bicycle in the military. We caught onto that and wanted to test the bicycle for military purposes, to see how a solider could get from point A to point B, because horses and cavalry were beginning to get pushed out. They tried shooting guns from a bicycle and it didn’t work, and so it died away. It was an experiment, and the country never really used the bicycle for combat duties.

A.W.: What made you re-enact the bicycle trip in 1974?

P.D.: I was going to do it alone in 1973, and I was outvoted. What better way to re-enact the 1897 trip than on the very same day they left, and go across the country to the ration stations that are now cities or towns on the same day that they did. We gave little lectures and talked to people. The value of the trip was twofold: It was in their honor and to show that the black students at the University of Montana could re-enact history and put our department on the map. People still talk about it to this day.

A.W.: Why did you choose to write “Ole Freedom” as a historical novel? Why not just research a nonfiction book?

P.D.: I thought that a fictional account of what happened with history was a better way to tell the story. People can relate to stories better than they can a history book. I wanted to create characters and the environment that families and individuals would enjoy and also to show that there was real compassion and hatred in society during that time. The better way to show it is to show the ways that people had to confront their own individual prejudices and to succeed through that.

A.W.: There is one point in the book where a white officer refers to an African-American as “son,” not “boy,” and it is not meant derogatively, but affectionately. Then you write, “Time stood still.”

P.D.: In the historical context of race relations, sometimes the dominant society will have a relationship that goes beyond color and race. In the building of those relationships, sometimes a person will slip into a different form of humanity where they accept the person as a person instead of accepting them as a color or a race. When those phrases are used, it illustrates that the person has achieved a personal behavior that exceeds or extends beyond what society has given. I did that a couple times just to show that there is compassion and that the relationships during that period of time weren’t all negative.

A.W.: From listening to you speak, “Ole Freedom” is the culmination of your thoughts and opinions of how you would like society to be and how different racial groups and ethnicities ought to co-exist. You think that relationships and empathy are key.

P.D.: In practical terms, it’s very hard to do until you get to know the person. Once you get to know somebody and you start to put worth on their relationship, that will open you up to accept and understand the other person. In society, we do have that. That’s what happens when you have relationships and you can break down and peel back the onion layers. You grow. That is what I was wanting to do with “Ole Freedom.” I want a reader to grow.