Damon Faust and business partner Ross Fielder have a vision: putting veterans’ skill sets to work in Haiti. It’s an experience Faust knows about this firsthand.

Faust, co-founder of the nonprofit Remote Emergency Training Solutions, put his skills as a combat veteran to use as a wildland firefighter. He has also worked with Team Rubicon, which gives veterans an opportunity to apply their military experience to disaster response, and Hero Client Rescue, which provides emergency medical services throughout Haiti.

The best version of himself, he will tell you, is when he is serving his community.

Veterans and victims of huge natural catastrophes have something in common: trauma. Helping others, Faust said, is a way to process the grief and confusion and guilt and pain that one may have experienced as an agent of war or otherwise.

Faust was born in Portland, then raised in a suburb of Sacramento. He joined the military, like many young people, to get out of where he was and to make his mom proud. He landed in combat arms and quickly realized he wanted to get out. He learned that if he did a National Guard stint, he might be able to get out of active duty. He did, and he went back to Sacramento for a year of service.

After he left, Faust’s unit received orders to go to Iraq. Faust felt an obligation to some of the younger guys still there. He had taught some of them to drive a stick shift and had built a solid bond in the year they trained together. He re-enlisted in active duty and spent all of 2005 in Iraq with the Army.

Suzanne Zalokar: Tell me what impression your time in Iraq left on you?

Damon Faust: While in Iraq, I lost a good friend, and lots of my friends were injured pretty bad. Somewhere there, I realized that I wanted more. My military service kind of fucks me to this day. On the other hand, if I hadn’t gone to Iraq, I wouldn’t have found the motivation to want to do something different. It was love-hate and a catalyst for change in my life.

One of the lingering things that always sticks with me: Underneath all of that chaos and violence and ugly and hatred, I saw benevolence and compassion – and not just between guys in my unit, but between guys in my unit and Iraqi civilians and between others. It was very interesting to me that in all of that chaos, there was still love.

S.Z.: Where are you now, with Remote Emergency Training Solutions?

D.F.: I have a friend who is the CEO of Hero Client Rescue, (a service that works to build a strong emergency response capacity in underserved communities worldwide). She’s been in Haiti since the earthquake (in 2010).

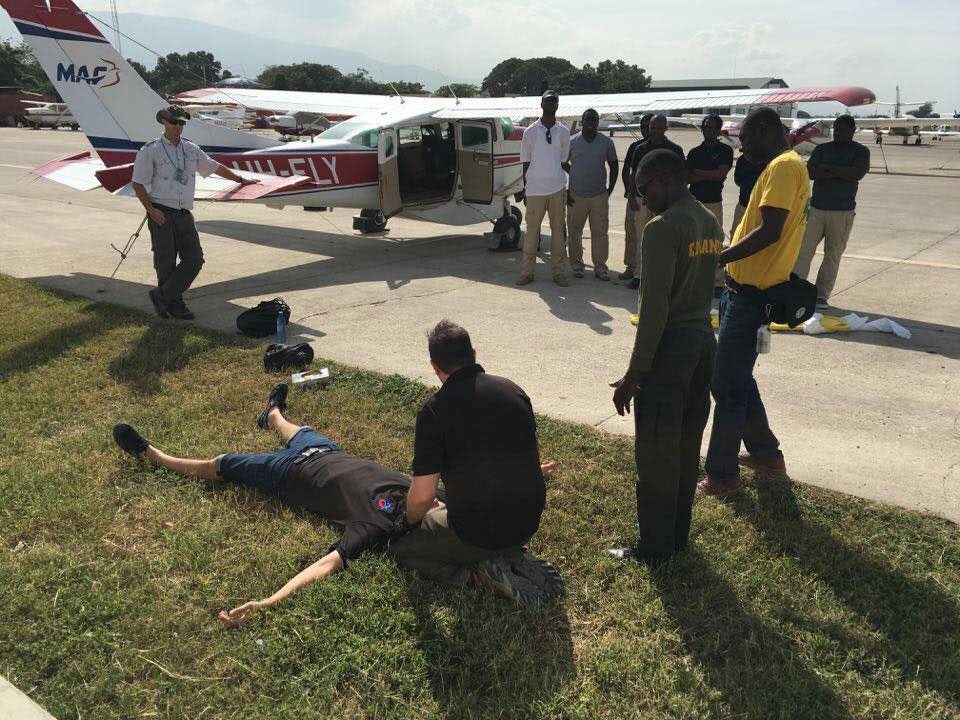

I told her I wanted to put my skills to use, and that evolved into me coming down there and helping her do some really cool training with the Haitian Coast Guard. None of them had any sort of first-aid training. It was really great to give them some of those skills. One of the things I kept reiterating was whether or not you use this in your day-to-day helping your community, these are skills that you can use for your family and your friends.

S.Z.: You have this freedom to go to Haiti in part because of the compensation you receive from the military, meaning you don’t have to get time off from work to go. Some poeple might think you are living the dream. What is that like?

D.F.: I am dependent on the system, and that terrifies me.

My girls have changed my perspective. I have a 5- and a 3-year-old. That is one of the reasons that I do a lot of volunteer work. I have a deep fear that they will describe their dad as an isolated, shut-in vet who drinks too much in the garage. I haven’t done that in a long time. I was working through some things in my head. I still struggle with depression and things like that, but I’m finding other ways to use my time, ways to use those hours.

You know that compensation from the VA? It can make you feel that your power has been stripped. My ex-wife participated in the caregiver program, which the VA created for modern war fighters. For us, a spouse could become a caregiver, and they would get compensation too. That changed our whole family dynamic.

One of the things it did was strip my role in the household, or I felt it did. I no longer felt like a partner. I felt like someone who was in need of care. And my ex-wife no longer felt like my partner either. She felt like a caregiver.

I’m conflicted though. Without the VA’s help, I would be on the streets.

I’ve spent seven to eight years seeing a mental health therapist, and I have used the system through the VA or the Returning Veterans Project.

Given the resources to heal at their own pace – heal isn’t the right word – but to make sense of it all and to find their passion again? It might take some guys or gals a year or two, or like me it might take a decade. But once you find that passion, you continue to support it and then organically you find the capacity to live again.

S.Z.: Tell me about your trip to Haiti in January.

D.F.: I was there for about two weeks. I’ve been on international and domestic disaster relief missions, and I have stepped on the rubble of communities in the aftermath. I had strong feelings in my heart seeing how rough folks have it there.

I know we have issues with hunger and homelessness and access to health care in vulnerable populations in the states, in Portland. The thing about Haiti is it is so much more rampant and in your face. In the states, we’ve pushed our vulnerable populations to the corners. In Haiti, you are walking hand-in-hand with those populations.

S.Z.: What did you do there?

D.F.: I did a lot of training. The level of first-aid knowledge in Haiti is subpar. There is no other way to describe it; it is pretty much nonexistent. For someone who is having a seizure, a portion of the Haitian people believe that you should throw water on them and slap them. I saw that firsthand. Just the very base level of first aid is nonexistent.

There is some curriculum, and they are certifying folks, but you don’t see police stations and firehouses. You don’t see your public service agents out there in Haiti. It felt very lonely in that regard.

It’s a very lonely feeling to be in a country or situation, and this would be similar to Iraq too, to be in a developing country or a place where if you get hurt and you need care, it is going to be hard to come by.

Here in Portland, if I twisted my knee and fell down and hit my head, there are countless medical options to get me to care. It’s just not that way in (other places).

S.Z.: You were kind of scouting too, right?

D.F.: The mission that we did in January was to identify a role for our veterans from Post 134 in Portland. And bring a group of them over to Haiti to do similar training.

(Remote Emergency Training Solutions) has had someone in Haiti since March 15. He has been training Haitian EMTs in basic first aid and working in an ambulance.

Haiti is definitely full of missionaries and NGOs and clean-water groups. I kept hearing that (Haiti) is the NGOs’ paradise – you can’t toss a stone without hitting a missionary group in Haiti.

S.Z.: How is it possible that there are all of these people there giving aid and it doesn’t get any better?

D.F.: I only have the 15 days there or so, but there are some theories that I’ve heard. One, in Port-Au-Prince you have a whole culture, a whole society that has PTSD from experiencing that earthquake, right? There are folks still walking around shell-shocked.

Also, the Haitian people are very much for the present and living today. I met some groups in the orphanages over there. If a mother has a family of three, not all of those kiddos are going to eat every day. They will rotate.

There is this cultural norm of “if we are breathing right now, then things are good.” There is no expectation of breathing tomorrow. It’s hard.

S.Z.: For a person who is experiencing PTSD, how does surrounding yourself with people in crisis help?

D.F.: I think that is what it’s about. The long and short of it. Why would I put myself in an environment where I would be exposed to more trauma when I am struggling with my own trauma?

I am one of the better versions of myself when I am immersed in a community or a situation where there is a need for me. I’m able to snap back to this higher functioning to where I’m very aware of everything that is going on around me – situational awareness. I’m very empathetic to other folks’ needs, and I read people a lot faster than most people can.

I’m good in a crisis. I know a lot of veterans who will tell you the same thing. We function better in those stressful situations where there is trauma or danger or threats around us. The USA did a really good job of training us to do that.

S.Z.: And where do you find that when you are at home?

D.F.: When I’m back in the states – when I am not doing fires or disasters or hanging with my girls – every second seems long or distorted. I’m not even connected to all of them. I’m sweeping through most of them. You know? I’m disengaged, watching television, and I look up and four hours have gone by compared to when I am in Haiti or Iraq, where I am living every second.

There is this draw to connect to the present moment because I believe I have lived in such a state of mindfulness. In Iraq, I was mindful of every single moment of every day. You had to be. The same thing happens when I go to a place like Haiti. I become very in tune into the world around me and into my own self. My body. My mind.

Same thing happens when I go on wildland fires. That version of me – he’s pretty cool. I really like that guy. He does a lot of good work.

Now I am reidentifying or connecting with this version of myself. It is putting others in front of me and serving something that is bigger than me: my community, the less fortunate. It makes me feel alive. I struggle with, when I’m not (serving others), being present and feeling connected to anything.

The crew this June, they want to “be in it” again, if you will. They want to experience that part of themselves.

S.Z.: A lot of people don’t do well in traumatic situations. Thank you for doing it.

D.F.: That’s it right there. These skills we learned while in the service can be utilized. Our situational awareness is heightened. Our ability to defuse situations is heightened. All those skills that don’t transfer unless you become a cop. If you are working at Hewlett-Packard, they don’t really care what your situational awareness is. If you work at Nike, they don’t really care that you can defuse a crowd of 30 people by your posture and your voice. So this is trying to find places where veterans can use those skills.

A lot of us veterans, we were put in situations where we had to dial in really quickly and figure out how to (survive). Now it is with us. It’s not going anywhere. I think our goal, at the post (Post 134 in Portland) is to find local mission here in Portland and to spots like Haiti to where these veterans can use those skills again. And do it through peaceful mechanisms.