David Slader first laid his hands on a painting signed “B. Pat” inside a decommissioned jail, located in the cellar of Coquille’s old city hall building.

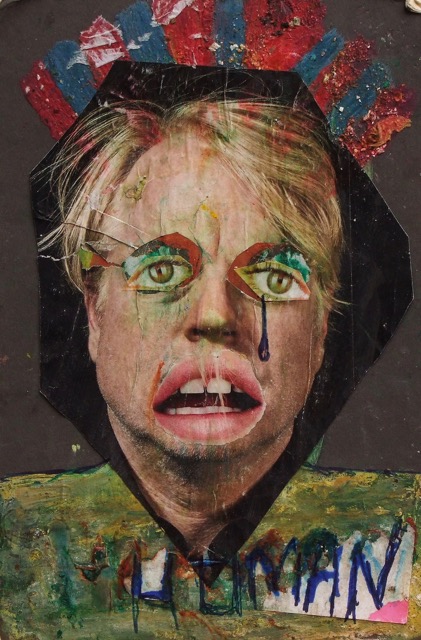

The clown-like face painted with crushed-candy pigment was as raw as it was disturbing.

“It’s a window into a very troubled mind,” Slader said. “And that’s what makes it so powerful.”

Across the self-portrait was scrawled the phrase “Human Being.”

It reminded Slader of an exhibit he’d seen about three years earlier in New York City at a folk art museum. It was a collection created by the French artist Jean Dubuffet, whose style was modeled after the works of mental hospital patients and children.

Dubuffet coined the phrase “art brut” to describe art created outside of cultural norms and untethered by formal training.

“Much of the art brut work is from mental patients,” Slader said. As he pointed to B. Pat’s self-portrait, now lying on his dining room table, he said, “As you can see, this probably fits that criteria in some way.”

Slader had found the piece while rifling through the remains of an inmate art show called “Cries from the Cage,” which toured Oregon in 2011.

He was looking for artists to showcase in July alongside his latest collection of oil paintings at Gallery 114 in the Pearl District, and he thought Oregon’s prisons might hold some promising talent.

An attorney-turned-artist, Slader spent the last decade of his legal career suing the Archdiocese of Portland on behalf of sex abuse victims. But he remembered how in his earlier days as a criminal defense lawyer, an incarcerated client had paid him with paintings of iconic African-Americans.

He Googled “Oregon prison art,” and it led him to a website of the same name.

Bandon resident Victoria Tierney had created the site to showcase and help sell the work of incarcerated artists she’d featured in an exhibit several years earlier. She sent Slader to the old city hall building in Coquille to select some items for the show.

Tierney had suggested that Slader consider artists Jerome Sloan and David Drenth.

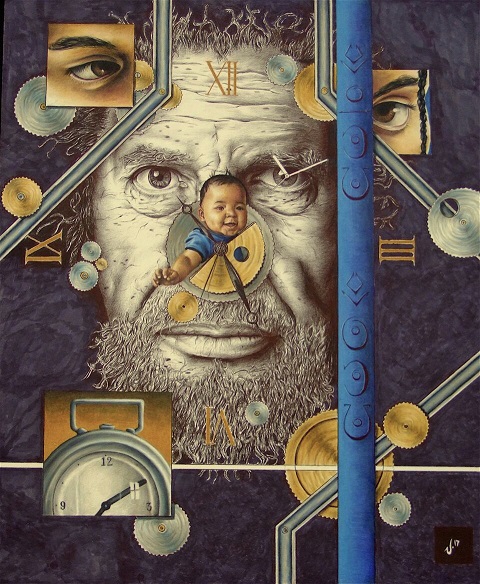

Sloan, an inmate at Snake River Correctional Institution in Eastern Oregon, skillfully draws photo-realistic portraits interwoven with objects, often clock parts, and his own alphabet of symbols. His “Time Series” will be featured at the gallery.

He uses proceeds from his art sales to help support his son, who was born after he was incarcerated. He described his series as: “about how I look at time now. I now see that time is about my family and how the next generation will be better than me.”

Drenth is an Oregon State Penitentiary inmate whose 5-foot long, brightly colored murals incorporate cubism and metaphoric surrealism.

The show, aptly titled “Human Being,” kicks off July 5 with an auction from 6 to 8 p.m. to benefit the Oregon Justice Resource Center, followed by its official opening on First Thursday from 6 to 9 p.m.

Drenth spoke to Street Roots from Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem, where he earned an associate degree in art through Chemeketa Community College.

“Look at the art – look at how much hope it’s given me,” he said. “I wouldn’t even be talking to you if it wasn’t for the art.”

FURTHER READING: A former inmate’s true story of hope, change and inspiration through art

Drenth said he works about 40 hours each week cleaning up the prison yard, for which he earns $40 a month. It’s about the same amount he spends on the art supplies for each piece that he creates within the walls of his 6-foot by 7 1/2-foot cell.

“A bag of coffee is $10, and pencils are $1.39 each,” he said. “I have to make a choice between my art supplies and if I want to drink coffee.

“One of the reasons I started doing the art,” he said, “is because I realized that prison jobs don’t pay that much, so I am going to have to somehow make more than I am able to make in here to be able to survive in here.”

FURTHER READING: Inside Oregon’s prison workforce: Exploitation or opportunity?

Both Sloan and Drenth are serving life sentences for their roles in murders that occurred decades ago.

Drenth, 58, was 27 when he was sentenced, and Sloan, 42, was 20. Neither man pulled the trigger himself, but in Oregon, anyone in a group that commits a felony that results in a loss of life is guilty of murder.

Time is a common theme in both their work, whether an hourglass or ticking hands of a clock.

“Sometimes it seems like time gets skewed or distorted,” Drenth said. “I’m in the same place for 34 years, and time isn’t even real to me anymore.”

Tierney has met all three of the inmate artists, and she said while Sloan and Drenth “are more socially conscious,” B. Pat was more inwardly focused.

“He’s a very troubled soul – he knows he’s a very troubled soul. He’s done things that he’s not proud of, and nobody would be,” she said. “He is a man so extremely in touch with his angst, with his suffering – like he’s living in hell. And he expresses that in such a way that it can be very moving.

“Strangely enough, he’s the one that’s out of prison,” she said.

Alongside Sloan’s beautifully intricate pencil portraiture and Drenth’s clean lines and well-composed panoramas, B. Pat’s creations, composed from shampoo, coffee, toothpaste and whatever else he could get his hands on, have a childlike quality.

His pen drawings, on the other hand, are quite explicit.

B. Pat’s actual name is Vernon Bernard Patrick, and he made headlines in 2009 when he lured a homeless woman to a Portland motel room where he brutally beat her.

Tierney first visited him to discuss showing his art when he was at the Justice Center in downtown Portland.

He had sent her a letter that said: “I am 6’, 4” and 300 lbs.; I am crammed into this little 7 x 5 foot cell. It’s awful, hideously synchronized with descended anguish and chaos. I would be interested in giving you some works for show.”

She remembers he was “a sight to behold.”

“He was this huge black guy wearing pink pajamas,” she said. “We had a very interesting afternoon in which he told me he had been brought up illiterate, and only in jail had he learned to read. And he had become quite the intellectual in his own personal way. This guy read Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. He was fascinated by time.”

B. Pat served his sentence, and after his release, Tierney’s contact with him ended. Neither Tierney nor Slader were able to determine his whereabouts to notify him of the show until recently, when he contacted Slader from Washington County Jail. He was arrested on charges of stalking, parole violation and first-degree sex abuse charges following two separate arrests in May.

Through a friend of B. Pat’s, Slader was able to secure a great deal more of his artwork to feature in his show.

“Some of these images are among the most powerful art I have ever seen,” he said.

“In no way is my admiration for his art an admiration for any other part of him,” Slader said. “But even in the soul of someone that has harmed others, there is this inherent urge to create that says, you’re a human being.”

Gallery 114 is a cooperative, owned and operated by 11 artists who all pay dues and take turns designing their own exhibits.

This structure, free of commercial pressures, allows them to show strong, original exciting art that isn’t necessarily marketable, Slader said.

Slader’s style of abstract portraiture began with close-ups of men. He drew on his former clients who were abused by Catholic priests for inspiration. He said many of their siblings didn’t survive the abuse, and killed themselves, “either the fast way or the slow way.” But his clients were tough and tenacious survivors whom he admired, he said.

The collection of abstract female nudes that he’ll showcase in July was almost entirely painted after the November election.

“The traditional female figure in Western art is a passive figure,” he said. He wanted his women to be in control, and he said it was his intention to use eroticism as power.

“If you can have full frontal nudity, and still be self-assured, that’s a real strong statement,” he said.

He said while he knew of more than a dozen talented local artists he could feature alongside his work, he wanted his show to have meaning.

“Few Oregon towns have as many citizens as the 14,000 men and women locked up in our prisons,” Slader said. “Once those doors close, only family and a small population of state employees remain conscious of their existence.”

Drenth said he hopes gallery visitors will understand that there are two sides to his work, which uses the juxtaposition of time and bondage against bright carnival colors.

“There is a lot of pain there, but there is a bright side to it, too,” he said.

“People had no idea how talented some of these guys that are locked behind bars,” Tierney said. “People only know them for the bad things they’ve done, but in fact they are human beings, and they are oftentimes very extremely talented and are very deep and profound in their take on life – they have definitely seen the dark side.”

Email staff writer Emily Green at emily@streetroots.org; follow her on Twitter @GreenWrites