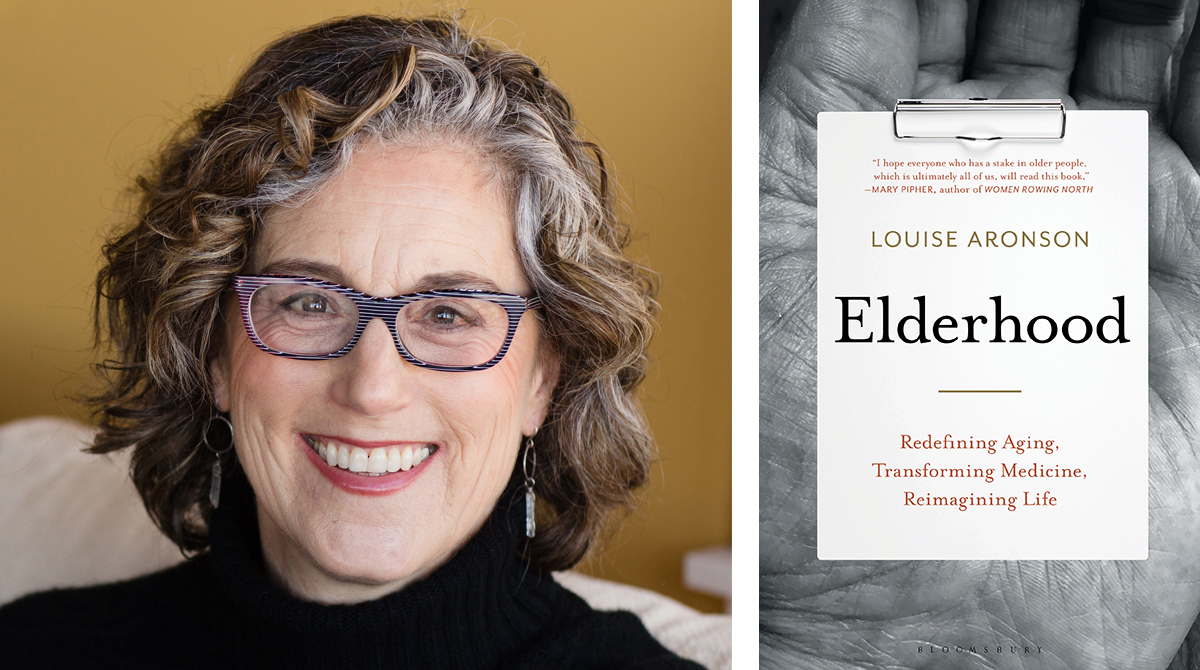

With improvements to health care and quality of life in the 20th century, the American life expectancy lengthened. Now most people can expect to spend decades in life’s final stage. But society hasn’t adapted to this new reality, and neither has medicine, argues Louise Aronson, an award-winning author and physician, in her new book, “Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life.”

Aronson will be at Powell’s City of Books in the Pearl District at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, June 19, for a reading and book signing.

Interwoven with stories from her career as a geriatrician and personal experiences as she confronted her parents’ aging, Aronson reveals a reality in which doctors receive little training in the complexities of treating the elderly. She also explores other issues that can complicate a person’s senior years, such as how the design of physical spaces often exclude those less agile and how a landscape of growing inequality is leaving many older adults with little savings to rely on in their retirement. She shows that while the elderly are a burgeoning segment of the population, in many ways, they remain invisible.

Aronson recently spoke from her home in San Francisco with Street Roots about some of the issues she outlines in her book.

Emily Green: How have perceptions of the elderly systemically impacted their medical care?

Louise Aronson: In the same way it’s impacted everything else; people think it’s a waste of time and resources. Generally, and this goes back a long time and across cultures, old age is considered beginning somewhere between the ages of 60 and 70. If you’re homeless, if you’ve been incarcerated a long time, if you’ve had a really rough life, it can start even sooner, but we’ve basically acted like it’s this one thing and older adults are not worth anything.

There are two problems with that. One is you start writing off one category of person and we’re all in trouble pretty quickly – it’s another “ism.”

FURTHER READING: A toolkit for pushing back against ageism

The second is that it has created a self-fulfilling situation where we don’t do things or design things with older people in mind, and then we say, “They don’t come here anyway.”

In medicine, we’ve done both those things. Sometimes older people are considered not as worthy of care as younger people, and consequently, they don’t get very good care. They don’t get timely attention, and they get what we call undertreated. Other times, clinicians treat somebody who’s 80 in the exact same way they would treat somebody who is 40 – treating the disease as opposed to treating the illness, which is the disease in a specific person. And that does huge amounts of harm to older people, which is well documented.

Most research and studies, even on people who are old, don’t include old people, but then we apply the results to them even though we’ve already said they’re different.

In medical education, people get hours to a week or two of training in geriatrics, although older patients are a huge percentage of out-patient care and nearly half of in-patient care. Meanwhile, clinicians get months of pediatrics and years of adult medicine.

Physiologically, socially and psychologically, people are different over the age span. If you look at pediatrics for example, you have people who specialize in newborns, in toddlers or kids, people who specialize in teens and young adults. In adult medicine, we have relatively few people who think about old people, although the numbers there are growing, but we tend to just treat older people as if they are older and nothing else matters – just an age that’s listed on a chart, so people aren’t trained in the physiologic changes in the older body, in the increases in risk and decreases in benefits of many treatments. Although, sometimes it’s the other way around – the benefit goes way up and the risk goes down.

We have women’s health and children’s hospitals, and others, but we tend not to think of this part of the population that actually uses a disproportionately higher amount of health care.

We also don’t think of them as the diverse population they are. A 70-year-old is not a 70-year-old is not a 70-year-old. In old age, people don’t progress through the stages predictably the way we do in childhood and adulthood. It has as much to do with function and health as it does with chronological age. We don’t acknowledge there are these subcategories, and for an older person, knowing the age is not enough information, you must also know how they are functioning because an 85-year-old who’s working and traveling and going hiking and walking through the city could be a better candidate for a certain procedure than a 68-year-old who’s on oxygen and in a wheelchair.

Green: I have two 70-year-old women in my extended family. One is frail; her health is deteriorating; she’s often talking about her ailments and doctor’s visits. The other one is still working, hiking, really thriving, appears very healthy. Part of this, as you write, is biological, but not all of it. How much of how quickly you progress through those stages is in an individual’s control versus out of their control?

Aronson: There’s a little bit of genetics. We know these people who are called super agers, who tend to look and function as the average person does decades earlier. There’s definitely genetics to that, and people who live into their 90s or 100s tend to have siblings who do, but that’s actually a relatively small contributor.

Other things come into play. Some of it is luck. Were you in a bad car accident? Did something horrible and traumatic happen to you? Those things really age a person. Another part of it is behaviors. And this is one of the great things that people don’t realize, is that yes, we always hear about exercise and diet, and people will say, “I’m 80. What difference could it possibly make?” Or, “I’m already 50, what difference could it possibly make?” And it turns out these things make a difference at all ages, in terms of people’s function, how they feel and decreasing their health risks.

It’s better not to smoke. It’s better to keep your weight at least near the normal range. It’s better to be physically active. People who have at least a couple of strong social relationships also tend to do better, as do people who have a sense of humor, which I think is somewhat of a marker for resilience. The ability to say, “I can’t do this anymore, but it’s not that I’m going to stop doing it; I’m going to do it a different way.” Or, “What else can I do that will give me that same satisfaction?” People who do those various things tend to be happier and more functional for a longer period of time as they age.

Green: I found one story in your book particularly disturbing, and that was about a patient who you call “Dimitri,” who was nearly catatonic and his family was fearing the worst, and it turned out his symptoms were the result of what you call the “prescribing cascade.” Can you describe how this happens, and also, is this a prevalent problem in geriatric medicine?

Aronson: What happened medically to this guy was he had a new symptom; he had a medicine prescribed for it. That helped with the symptom, but no one stopped him from continuing to take the medication, and it caused another symptom, and then he went to another doctor for the other symptom, and this is the cascade, and so on. Each one caused a side effect, which was then treated by someone else with another medicine, and eventually he ended up looking like he had end-stage Parkinson’s disease. The clue for me in that story was that it happened much too quickly for Parkinson’s disease. And so I took a risk, and I stopped them all, and he just became one of the most highly functional people in the nursing home.

He got a girlfriend and was a leader in the community, and it was great. But most geriatricians will have stories like this. You don’t always bring the person back to be the community leader, but you can make people feel much better.

It happens, generally, because these days we have such a fractured health care system and often people have different doctors for different organ systems. Even doctors who are supposed to be managing the whole thing will have something like 15 minutes with their patient, which if you have a person with complicated health problems, or a person who, as Dimitri, as he was drugged was moving more slowly, you still get 15 minutes. You get the same amount of time as you get for the 17-year-old who twisted his ankle, so it’s really prohibitive for doctors doing as well as they might.

But it happens pretty commonly, so older adults are disproportionately likely to end up in the hospital or dead because of what we call adverse drug reactions. And those can be from over-the-counter medicines, they can be from a prescribing cascade like this, or they can even be from simple common medicines like for diabetes, for some of the heart conditions that are common as people age, and that’s, again, because clinicians don’t think about how the body is different in elderhood from adulthood.

And every geriatrician I know, and a lot of other doctors, have stories like this, but one does wonder if it’s just the tip of the iceberg, because so often a person’s pretty old and they’re getting sick, or they have a few conditions and they get worse, people say, “What do you expect? They’re old.” When sometimes, it really is what happened medically.

This was actually one of the things that got me interested in geriatrics because I saw this happen with a patient when I was in the hospital as a resident, where the cardiologist said, “It’s done. Let’s just get him on to hospice.” And I started taking him off medicines to put the man in hospice, and every medicine I took him off, he got better. And then I started reading about this and talking to other people, so I sent him home, and did he eventually die of heart disease? He did, he died later that year, but he got a lot of nice time at home with his family first.

Actually, a cousin of my mother’s called me just a few weeks ago about her husband, who was doing worse suddenly, and she said, “He’s not doing well, he has a million problems, but he is just so much worse this last couple of days.” And I said, “Has any medicine been changed?” And she said, “The doctor increased his medicine, but he’s been on it for years.” I said, “Stop the increase.” And she called me two days later and she said, “Back to normal.”

Green: Oregon is a Death with Dignity state. Are there some ways that we could be tailoring the way we look at medically assisted suicide to make it more accessible and realistic for senior citizens?

Aronson: So many of my patients are unable to do the steps. Maybe they had strokes, or they have dementia or underlying illnesses. It was really designed with a high-functioning adult person in mind. It doesn’t think about hand arthritis: Can I deal with these medicines? It doesn’t think about vision or how swallowing can become harder once people are in their 80s or 90s. It doesn’t think about how are you going to have the ability to think clearly enough that people can trust that this is really what you want at that moment. Does that put you in an ethical quandary?

New York state passed dementia-related laws, which allow people to stop eating or have their feeding stopped at a certain, pretty advanced, phase, but so much of the assistance in dying really just doesn’t touch the oldest people. Once people are dying in their 80s and 90s, their chances of being frail or having visual problems or hand problems or some dementia really go up, and they’re just excluded from this thing that’s a right for many people these days, in some states anyway, like Oregon.

FURTHER READING: Defending death with dignity: Barbara Roberts, Barbara Coombs Lee reflect on decades-long effort

Green: If I’m an elderly person, how would you suggest I advocate for myself when I come in contact with doctors and nurses? Are there any questions I should be asking when I get a new medication or I’m considering surgery?

Aronson: You should ask, are there geriatricians in the area that might advise, if it’s a big decision. It’s worth asking when you get a new medication, what are the side effects? Do we know how this functions in a person my age? Is there anything else about my health or diseases that are going to increase my risk from this? What should I be looking for?

In terms of surgery, some places have started prehab clinics. We’ve all heard of rehab after surgery, but this is prehab, and this is to get someone healthier before surgery, which decreases the risk of complications and the time in the hospital and increases the chances of a good recovery. So asking for this sort of program, these are things that could really make a difference for an older adult.

I think advocating in people’s communities for elderhood-specific care of various types would really make a difference, and just keep asking for it, because people respond to markets these days.

Green: For those of us with aging parents or grandparents, what would you like us to know about the way that we should be interacting with our older family members and things we could do that might be helpful when it comes to issues concerning their health?

Aronson: Generally, there’s a tension between the older person and the younger members of the family or friend circle, in what their top priorities are. For the older person, it’s often about independence. For the younger people, it’s about safety for the older person. I think that leads the younger people to put restrictions and sort of impoverish the older person’s life. If the older person can say for her- or himself, “This is an OK risk for me, so I might end up on the floor; I get that. But I’d really rather be here, and I don’t want you looking at me through a camera. I deserve privacy.”

I think recognizing that difference in values and thinking about what you would want for yourself. It turns out, we change in some significant ways and we don’t change in other ways, and it’s the rare person that really likes other people telling them what to do or making decisions for them. So don’t infantilize an older person. They’re older, and they may process things a little more slowly, but they’re not a child. This should be a collaborative decision toward something that feels good for everybody.

Other things are to really sit down and help people to start thinking about what they value most and what doesn’t matter so much to them.

There’s a card game called Go Wish, and you can pass out these cards and everybody gets a certain number, and then everybody puts them into three piles: These are my top priorities, these ones I don’t really care about, and these are in the middle. People learn a lot about each other, and it’s a nice way of sorting out values.

There’s also a great online tool; it’s called Prepare for Your Care. It’s reading-level appropriate for a huge range of people, and helpful to get people to think.

The most helpful thing is to say, “This is what we can do to give you the old age that you want. Old age lasts decades, but we don’t know what’s going to happen to anyone, so let’s get ready now, and that way I’ll know what to do to help you, you’ll know what you want, we can be clear with everyone, and then you go about leading your life and if something happens, we are as prepared as we can be to give you the care that you want and the life that you want.”

Green: In Multnomah County and in Clark County, our neighboring county to the north, the greatest increase in homelessness recently has been among seniors. Here at Street Roots, where we create income opportunities for people struggling with extreme poverty, we have quite a few seniors that sell our newspaper, including three women in their 70s. What are your thoughts on this issue of increased homelessness among the elderly?

Aronson: People didn’t always plan to live as long as we now do; things also got much more expensive. When people are asked when they are younger or middle aged, have they saved enough for retirement, they’ll say yes. But if they can actually imagine themselves and think about what they enjoy doing and how they want to live, or even more importantly things like, I’d like to have my own apartment, I’d like to go eat every day, they imagine they have more money than they will.

And then there’s housing inequity, where the prices go up and up, and more people who would have been fine if things had stayed the same, really aren’t. That is so ubiquitous, and it’s crossing all different populations, that it’s one of those things that really needs to come at the policy level.

We need to help people think about their old age.

People in their 70s are the fastest-growing segment of the workforce, but people imagine, “I’m going to retire.” The notion of retirement was isolated to the 20th century, after the industrial revolution. What’s happening now has happened throughout history: The rich elderly were OK, and everyone else got poor. The first hospitals were poorhouses, and they were mostly filled with old people, so we can either go back to that horrible historical precedent, or we can start planning to create communities that allow people to age in place, that allow people to stop the more physically, or hourly intensive labor of adulthood and move into more part time jobs that supplement their income as they get older and enable them to stay out of homelessness and out of hunger.

Frankly, people who are productive, who are engaged, are happier than people who aren’t, in all income groups. So really thinking about what sorts of work can people do, where are they going to be able to live, how are we going to help people save money, and how are communities going to support people across the lifespan, are really important in ways that it wasn’t so much earlier because there were so few people who lived into old age.

Green: You also point out in your book that many people rely on undocumented immigrants to be caretakers for the elderly and their families because they are the only affordable option for in-home care. As we move into an era where the elderly portion of the population is expected to increase drastically, while at the same time the government is cracking down on illegal immigration, do you see a solution in sight for those who need in-home care but whose families are not wealthy?

Aronson: This is a huge issue that lots of us have been addressing. Just as the need is going up, the workforce is going down. Hopefully we won’t have this particular orientation forever, but I think a few things: When people have kids, they rarely question the need to care for those children in the way they feel it’s OK to opt out of caring for their parents. And I wonder if, as a culture, we have to think about our values.

I mean many people do all kinds of wonderful things for their parents, but it’s interesting that it’s considered optional or you’re the good person to do it, when that’s not the case for other care needs throughout the lifespan. Or if someone gets hurt at a younger age. Most caregivers actually already are family caregivers, so that brings me to a second point, which is that a recent study shows that only about 7% of caregivers of older adults get any training. Which is kind of crazy when you consider how much we’re asking people to do. They don’t know how to safely do various things or they just don’t know how to do it and they don’t want to hurt the person, and I think whenever a person feels like they don’t know what they’re doing, and there may be harms, you really don’t like the work as well. Training makes such a huge difference, so I think we need to start training people or making that more common knowledge. For example, most people have some sense of how to change a baby’s diaper, well how should a person use a cane, when they need a cane? Do we all know that? Most people will put the cane in the wrong hand.

Lastly, and this always feels a little utopian to me, but there’s lots of people who need jobs and can’t get them or people working jobs that aren’t really affordable for them, and if we could somehow pay people a living wage doing this work and/or have networks of people as they’re aging doing some of the care for other people. Lots of people are trying things out. There’s the Village Movement; there are other organizations where other volunteers support each other, time-banking; there are lots of innovative models where you try and really match up people who want work with people who need some help.

Email Senior Staff Reporter Emily Green at emily@streetroots.org. Follow her on Twitter @greenwrites.