The sun came out on a recent Thursday in Salem. For many of the attendees at the Timber Unity rally against cap-and-trade legislation, sunshine after record-setting rain in the previous month, was proof that God showed favor to Timber Unity. However, attendance was a far cry from the 10,000 people predicted on the Timber Unity website. Maybe 2,000 people traveled to the capital to protest Senate Bill 1530, the current proposed cap-and-trade legislation and the impetus for the movement.

Calling itself grassroots, Timber Unity began after agitation from the announcement of the closure of Stimson Lumber’s Forest Grove Mill. This agitation was especially felt by people like Jeff Leavy of Clatskanie, and other Oregon log truck drivers who had contracts with the mill.

Leavy contacted his state senator, Betsy Johnson, who informed him about House Bill 2020 and House Bill 2007, the cap-and-trade and diesel emission legislation that was on the table during the 2019 legislative session.

From shared fears about this legislation, Timber Unity was born. Across Oregon, it connected other truckers, loggers and natural-resource workers concerned about higher taxes, increased gas prices, and the threatened departure of corporations like Stimson Lumber.

The group’s early efforts culminated in a rally at the Capitol last June. Trucks and other large rigs formed convoys to Salem in a show of force. Simultaneously, 11 Republican lawmakers walked out on their vote for the legislation, killing the bill in the Senate.

Taken as a win for natural-resource industries and the movement itself, Timber Unity organizers spent the months between June and the Feb. 6 “Let’s Roll” rally fundraising and spreading the word in their communities. The call was to “Stand Up For Working Oregonians.” Gov. Kate Brown had promised to put reducing the state’s greenhouse gas emissions back on the table during the next legislative session, and Timber Unity promised to be there to protest.

A ROLE MODEL? Oregon could lead on cap-and-invest for carbon emissions (from August 2018)

The organization, with infusions of cash, political support and PR, navigated by former House Rep. Julie Parrish (R-West Linn), polished its players and honed in its message.

By the second rally, the faces of the movement and their narratives were well known among supporters. Jeff Leavy maintains the title as Timber Unity founder, a formerly non-political truck driver who was compelled to action over concerns of fuel hikes and costly upgrades.

Timber Unity messaging reaches audiences via board President Mike Pihl’s editorials and interviews. Pihl, owner of Pihl Logging in Vernonia, is also one of the stars of the History Channel’s "Ax Men," a reality TV show following loggers. Leavy and Pihl are the cowboys of their movement. Organizers Angelita Sanchez, a trucking company owner, and Marie Bowers, a multi-generational seed farmer, put a woman’s face on working Oregonians.

These folks, praised as heroes of the movement, are sending a message to people concerned for their industries, to “stand up” and run for office and change the Democratic majority in the state Legislature.

So while some arrived to rally around opposition to the newest version of the cap-and-trade bill, the stronger message of the rally was about changing the face of Oregon government.

SB 1530, an updated version of last year’s HB 2020, still aims to reduce Oregon’s greenhouse gas emissions to 45% below 1990 emission levels by 2035, and to achieve 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. This is achieved through forcing large greenhouse-gas-emitting industries to buy credits for each ton of greenhouse gas they emit.

Several provisions have been added to this current bill since last year to address supporting industries and workers through the transition, with staggered timelines across the state to transition to new fuel emission standards, and a “just transition fund” that would help retrain workers in less carbon-intensive economies.

The bill is expressed in its purpose to “promote the adaptation and resilience of natural and working lands, fish and wildlife resources, communities, the economy and this states infrastructure in the face of climate change and ocean acidification and to provide assistance to households, businesses, and workers impacted by climate change or by climate change policies.”

PHOTO ESSAY: Inside the lives of environmental activists

It is the emergency clause pertaining to climate change that Timber Unity supporters see as an overreaching form of “tyranny,” especially as the group does not have a cohesive message on climate change. The group is also concerned about what they see as a lack of transparency, which would prevent citizens from having access to information about how cap-and-trade funds are being spent.

Their call to the governor: Put cap and trade to a public vote.

The rally

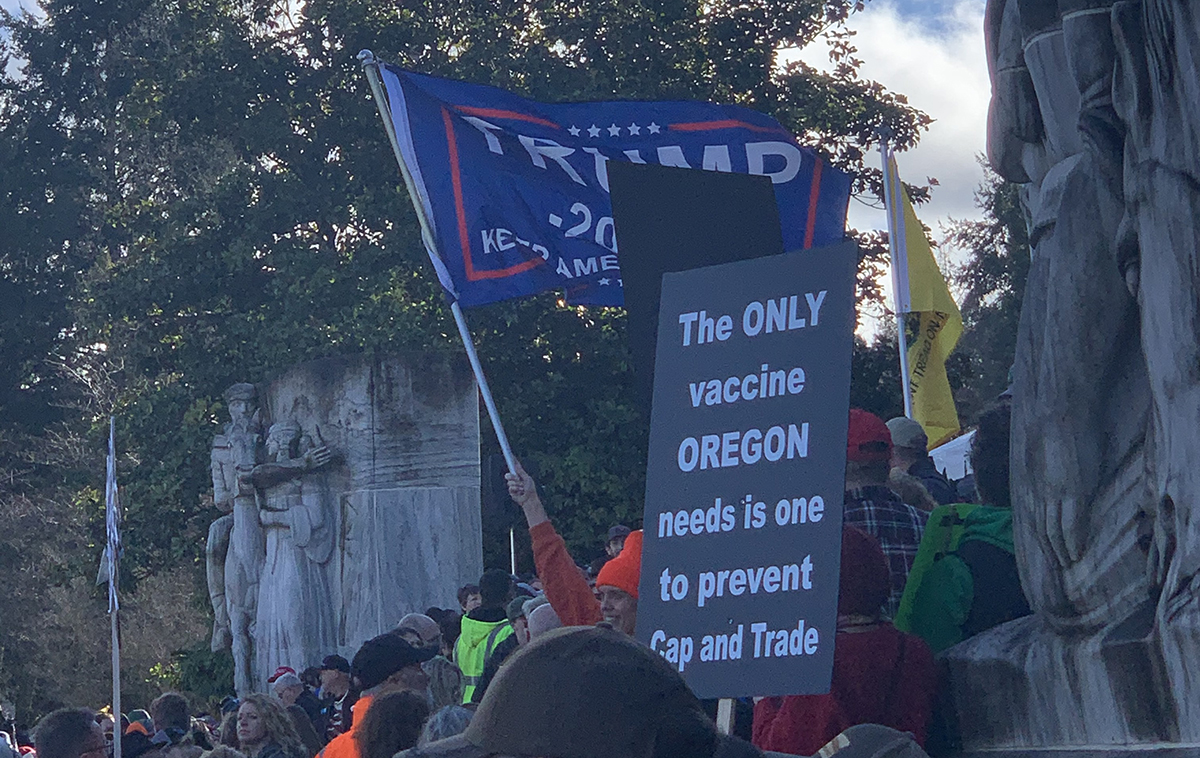

While their numbers weren’t as high as the first rally, and business in Salem went about as usual, horn blasts from circling big rigs could be heard all the way to the fourth floor of the Capitol, where the senators who sponsored SB 1530 have their offices. Semi trucks flew American flags, Oregon state flags with #Timber Unity added to them, and various banners with sentiments against cap and trade and for gun rights.

Former Rep. Parrish handed out Timber Unity “Courage & Conviction” awards to legislators who supported the cause, in between speakers from natural-resource industries, organizers and an environmental scientist from the Heartland Institute, a conservative market-based think tank, who told the crowd climate change isn’t real.

Q&A: Christian climate-change expert is on a mission to change the minds of faith-based deniers

Demonstrators wore work clothes and business logos, sweatshirts and hats hailing their role as workers in logging, truck driving, agriculture, feed store work and mining. If they weren’t wearing the heart of their industry on their sleeves, they donned MAGA hats and waved Trump 2020 flags. On the periphery of the crowd were State of Jefferson advocates, a movement for eastern Oregon and Northern California to form its own 51st state; Mothers For Bodily Autonomy, who opposed last year’s bill to mandate vaccines; Russian Old Believers; Three Percenters; and even a Patriot Prayer vehicle.

RADICAL RURAL RIGHT: How the Patriot movement is organizing throughout Oregon’s rural communities

Tasha Webb, a Timber Unity board member representing miners, spoke to the threat that awaited the state should they not heed this warning of their citizens to ditch cap and trade. She called it “a revenge that would not be served slow.”

Rob Gensorek, owner of Basin Tackle in Charleston, Ore., spoke about rural misrepresentation and demonization by urban liberal voters and Brown.

“They think you are a bunch of cousin-lovin’-missing-teeth-backwood-idiots who can’t make decisions for themselves,” he told the crowd.

He made a joke to the crowd about two things he says aren’t real, “green jobs and unicorns.”

A member of the Three Percenters I talked to implored me to “write the truth.” He entertained a few of my questions on the state Capitol about who Three Percenters are and why they support Timber Unity. He and two others wore Three Percenters sweatshirts and carried walkie-talkies or donned ear pieces. While they didn’t say so, I could see they were working as an informal sort of security, which Three Percenters often do as a paramilitary organization focusing on gun rights and limited government.

They told me about the gun-rights rally in Virginia. “That was us,” one of them had boasted. During the Republican walkout in June, Three Percenters offered “security, transportation and refuge” to the Republican senators.

When I asked what he believesd the “truth” was, he responded that Three Percenters were misrepresented.

“People think we’re white supremacists. We’re not white nationalists or neo-Nazis,” he insisted.

There was conviction when he said this; he was looking me in the eye.

I considered asking if he recognized it doesn’t take claiming white supremacy to be a white supremacist. In many ways, all it takes is being an Oregonian.

When Timber Unity supporters, largely white, multigenerational Oregonians, continue to speak to the threat to “our way of life,” they are invoking the white supremacist history of Oregon.

History

During the 1800s, Oregon was conquered for the United States through the transfer of large swaths of land to European, overland immigrants via the Donation Land Act of 1850. This transfer made official an effort to control and settle the western part of the continent by the U.S. government, at the devastating expense of Native communities. Begun formally with the Jefferson administration commissioning the Corps of Discovery to find navigable routes to explore and claim the West, it continued with the migration of thousands of Missouri farmers and overland immigrants via the Oregon Trail.

The Donation Land Act made official the claims of European settlers under the provisional government of the Oregon Territory, which formed as settlers arrived and began to claim land in the Willamette Valley.

The beneficiaries of the Donation Land Act of 1850 were clear: Claims were open to any person who was a resident of Oregon by December 1850, 18 years of age, and a white male citizen of the U.S. or a white non-citizen who declared intention to naturalize.

The size of the land claim was 320 acres for a single white male, and 640 for a married white male.

Land claims for new immigrants after 1850 were stipulated to be for males who were white and a citizen or non-citizen declaring intention to naturalize. The could claim 160 acres and 160 in the name of a wife.

Portland State University historian David A. Johnson said, “No previous land law in the United States had granted land to this extent for free. No subsequent land law of the U.S. would do so either.”

As Johnson explains in his Oregon Humanities lecture, “How The Donation Land Act Created the State of Oregon,” this transfer of natural-resource wealth to white men, the men who became the makers of the state and the writers of its Constitution, was both an intention and a consequence.

Exclusion laws were subsequently written into the state Constitution against Chinese and black immigrants by these early Oregonians. In the decades that followed, natural-resource industries began to develop and boom — from farming to timber, to fishing, to mining, compounding the prosperity of the largely white population of the state.

More European immigration followed in the late 18th and early 19th century to fulfill the working-class labor needs of those industries. These waves of immigrants formed and re-enforced the archetypal character of Oregon’s “working man” that still resonates today.

EXHIBIT: 2 sides of Oregon's history: Juxtaposing discrimination and resistance

Today, a gold-finished bronze statue stands on top of the Oregon Capitol. The Timber Unity rally drew its gaze to the statue, the “Oregon Pioneer,” more than once — pointing out the statue’s ax in hand and the tree stump he stands in front of. “That’s a logger,” many proclaimed.

This is not just Timber Unity’s birthright. And to focus on the movement as white supremacist would be disingenuous though, because the spoils of this power are not exclusively given to the rural workforce, Republicans or timber workers. All white multi-generational Oregonians inherit this history.

I am a person with white Oregon privilege, as a multi-generational Oregonian on both sides of my family, with ties to agriculture, timber and fishing. My European immigrant families derived wealth from the land, both as landowners and natural-resource workers. Some were working class; my grandparents worked in mills and canneries, but their identities and efforts are reflected in the accepted archetype of who an Oregonian is.

Sen. Cedric Hayden, from Fall Creek, a self-proclaimed “sixth-generation, covered-wagon Oregonian,” accepted a Courage and Conviction award from Parrish.

“They are going to cap and trade away our lifestyles and our livelihoods,” he warned. “I would call it cap and raid — on our ability to live, work and play in the timber, mining and farming industry and to do what we have done for hundreds of years without (government) involvement in a scheme that takes away our family’s traditions.”

When Hayden says “hundreds of years,” he means barely 200. He concludes, “If you pass this bill, you are going to kill my people.”

Identification with the white working class, along with a belief in the right to make a living off of the land and to take up arms to protect it, is in fact, historically, what makes a white Oregonian. In this way, Timber Unity’s resistance, and the factions that make up their supporters, makes complete sense. They are speaking to the core of what it means to be an Oregonian, demanding the government not intrude upon it. They do this from the pulpit of a grave denial — a denial that the threat of destabilization comes from the crisis of climate change.

As Shannon Poe, president of the American Mining Rights Association, suggests in her speech at the Capitol, this battle over entitlement extends far beyond any single environmental legislation. The fight, she said, “is about the soul of Oregon, and it is in your hands.”