Outrage over the recent police killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd has sparked ever larger street protests with participants demanding an end to police brutality against Black people and a radical transformation of our criminal justice system. Changes achieved benefit us all.

Hopefully this growing popular determination to confront racism and white supremacy will lead to action on other fronts, including for climate justice.

As a 2020 study in the journal Climate makes clear, climate change — for reasons of racism and private profit-making — also disproportionately punishes communities of color and the poor. The study explored the relationship between redlining, the historical practice of refusing home loans and insurance based on a neighborhood’s racial composition, and urban heat islands.

Q&A: The impact of the Fair Housing Act — and why it didn’t end redlining

The authors of the study, Jeremy S. Hoffman, Vivek Shandas and Nicholas Pendleton, examined temperature patterns in 108 U.S. cities or urban areas and found that 94% saw consistently higher land surface temperatures — as much as 13 degrees Fahrenheit — in formerly redlined areas compared to their non-redlined neighbors.

“We found that those urban neighborhoods that were denied municipal services and support for homeownership during the mid-20th century now contain the hottest areas in almost every one of the 108 cities we studied,” Shandas told The Oregonian in an interview published Jan. 20. “Our concern is that this systemic pattern suggests a woefully negligent planning system that hyper-privileged richer and whiter communities. As climate change brings hotter, more frequent and longer heat waves, the same historically underserved neighborhoods — often where lower-income households and communities of color still live — will, as a result, face the greatest impact.”

Urban heat islands

Temperatures can greatly vary in a single urban area. Climate scientists refer to localized areas of excessive heat as urban heat islands. Studies have identified two main causes for these heat islands. One is the density of impervious surface area: The greater the density, the hotter the land surface temperature. The other is the tree canopy: The greater the canopy, the cooler the land surface temperature.

STREET ROOTS REPORT: Portland's urban heat islands pose threat to lower-income residents

Not surprisingly, research shows that communities of color and the poor are the most common residents of urban heat islands. Hoffman, Shandas and Pendleton’s contribution is to show that the process by which communities of color and the poor came to live in these areas with more impervious surface area and fewer green spaces was to a large degree the “result of racism and market forces.”

Racism and redlining

Racism in housing has a long history in Portland. One example: in 1919, the Portland Realty Board adopted a rule declaring it unethical to sell a home in a white neighborhood to an African American or Chinese person. The rule remained in place until 1956.

Portland was no isolated case; racism shaped national housing policy as well. In 1933, Congress, as part of the New Deal, passed the Home Owners’ Loan Act, which established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The purpose of the HOLC was to help homeowners refinance mortgages currently in default to prevent foreclosure and, of course, reduce stress on the financial system. It did that by issuing bonds, using the funds to purchase housing loans from lenders, and then refinancing the original mortgages, offering homeowners easier terms.

BOOK REVIEW: How the real estate industry conspired against Black homeownership

Between 1935 and 1940, the HOLC drew residential “security” maps for 239 cities across the United States. These maps were made to assess the long-term value of real estate now owned by the federal government and the health of the banking industry. They were based on input from local appraisers and neighborhood surveys, and neighborhood demographics.

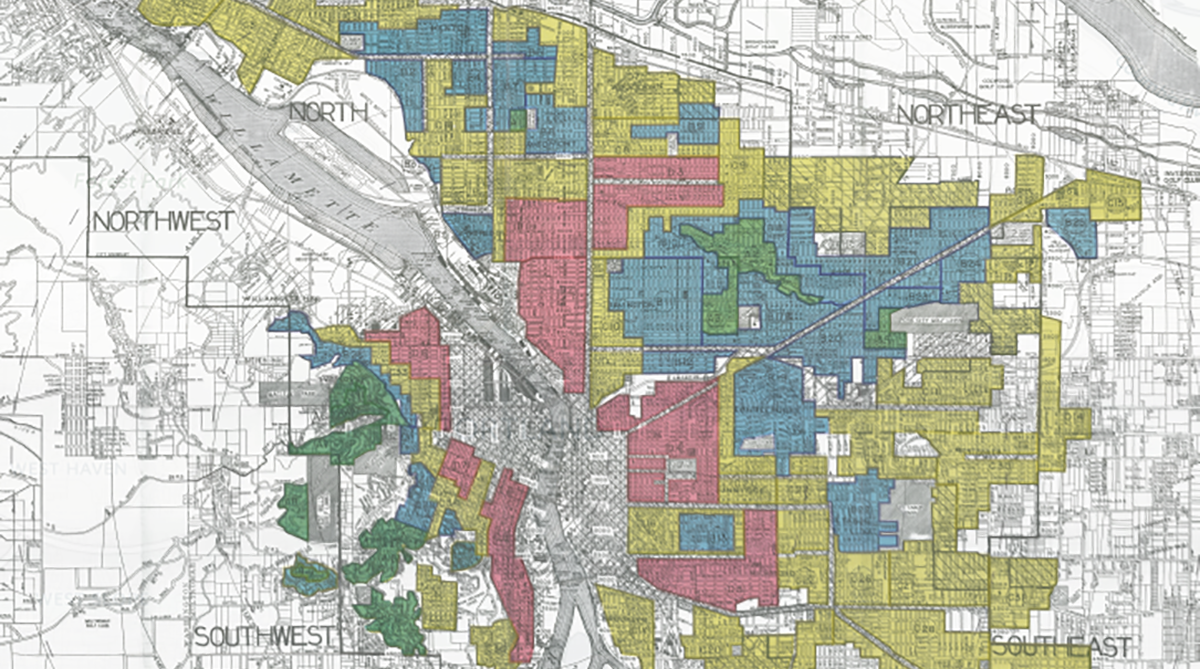

As Hoffman, Shandas and Pendleton describe, the HOLC, “created color-coded residential maps of 239 individual U.S. cities with populations over 40,000. HOLC maps distinguished neighborhoods that were considered ‘best’ and ‘hazardous’ for real estate investments (largely based on racial makeup), the latter of which was outlined in red, leading to the term ‘redlining.’ These ‘Residential Security’ maps reflect one of four categories ranging from ‘Best’ (A, outlined in green), ‘Still Desirable’ (B, outlined in blue), ‘Definitely Declining’ (C, outlined in yellow), to ‘Hazardous’ (D, outlined in red).”

This identification of problem neighborhoods with the racial makeup of the neighborhood was no accident. And because the maps were widely distributed to private financial institutions and other government bodies, they served to guide private mortgage lending as well as government urban planning in the years that followed. Areas outlined in red were almost always majority African American. And as a consequence of the rating system, those who lived in them had more difficulty getting home loans or upgrading their existing homes. Redlined neighborhoods were also targeted as prime locations for development of multi-unit buildings, industrial use and freeway construction.

In other words, urban heat islands are not just randomly distributed through an urban area. They are more often than not located in those previously redlined areas. Or in the words of the authors, “current maps of intra-urban heat echo the legacy of past planning policies.”

Redlining and the need for climate justice

Hoffman, Shandas and Pendleton condensed the 239 HOLC maps into a database of 108 U.S. cities. They excluded cities that were not mapped with all four HOLC security rating categories and in some cases had to remove overlapping security rating boundaries, or merge them because they were drawn in different years.

They then used land surface temperature maps generated in summer months between 2014 and 2017 to estimate land surface temperatures in all four color-coded neighborhoods in each of these 108 cities to determine whether there was a relationship between land surface temperature and the neighborhood ratings in each city.

As noted above, they found that present-day temperatures were noticeably higher in D-rated areas relative to A-rated areas in approximately 94% of the 108 cities. For the nation as a whole, D-rated areas were on average 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than A-rated areas. The greatest temperature ranges were found in urban areas in the South and West. Portland and Denver had the greatest D to A temperature differences, with their D-rated areas approximately 13 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than their A-rated areas.

The more extreme heat experienced by residents of these D-rated areas has real consequences. As Hoffman told The Oregonian, those living in these urban heat islands “are not only experiencing hotter heat waves with their associated health risks but also potentially suffering from higher energy bills, limited access to green spaces that alleviate stress and limited economic mobility at the same time.”

As this study clearly shows, we are not all in the same boat when it comes to climate change. Racial and class dimensions matter. Communities of color and the poor disproportionately suffer the most from global warming largely because of the way racism and profit-making combined to shape urbanization in the United States. As we mobilize to fight for a new climate policy, we must ensure that both our movement and its demands are rooted in a commitment to climate justice.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor emeritus of economics at Lewis & Clark College. Street Smart Economics is a periodic series written for Street Roots by professors emeriti in economics.