For eight months, houseless Portlanders made the large curb strip around Laurelhurst Park home, building community and working together to address the challenges of life on the streets. Then, on Nov. 19, amid Oregon’s biggest COVID-19 surge to date, heavy rains and near-freezing nights, the city cleared it out.

“When I got here today, everyone was broken, dismayed, and packing up and leaving,” said Jeff Du Bois. Du Bois was born four blocks to the northeast of the park and lived at the camp on and off. He came to help friends living at the camp as soon as he heard about the 9 a.m. sweep.

Within minutes of the sweep beginning, a scuffle broke out. Campers there said that employees of Rapid Response Bio Clean, a company the city’s Homelessness and Urban Camping Impact Reduction Program, or HUCIRP, contracts to carry out sweeps, had antagonized residents while breaking down the camps.

“He pushed me,” said Timmi, who did not want to give their last name. “He just kept getting in my face, putting himself inches from my face, calling me a ‘bitch’ repeatedly.”

The altercation, which was also described by other residents and observers, marked the start of an emotional day for residents as they watched their homes being torn down and tried to figure out where they would sleep that night.

The next day, Bobby Rush told Street Roots about his camp. “I had plants planted around my spot and everything. I replanted grass. I tried to make it nice,” said Rush.

Only two weeks prior, he had built his home with wood, nails, caulk and enough tarping to ensure it was insulated in hopes it would help him beat pneumonia, a particularly dangerous infection for Rush, who is HIV positive.

After losing his home on the first day of the sweep, Rush slept outside by a fire with friends, but he had trouble breathing. The next day, sitting in the remains of another camp, the floor littered with the parts of a home and rain falling in where a roof once was, he said, “I really do not know where I’m going.”

And he isn’t alone. None of the camp residents Street Roots spoke with knew for sure where they would sleep or believed they had any safe options.

“They keep telling us, ‘You can’t stay here, you can’t stay here, you can’t stay here!’” said Scott Rupp, who had lived at the camp. “There’s nowhere I can stay.”

Mayor Ted Wheeler’s office issued a statement on preparations behind clearing the Laurelhurst camp:

“We created and offered alternative warm, dry indoor spaces for people to go where they have access to hygiene, water, food and services. We posted the site clearly and with ample warning so people were aware that a change was needed.

“Moving forward, we will continue providing compassionate alternatives to street camping while preventing large-scale camps that block sidewalks and rights of way, creating public safety and health risks and obstructing access to shared community spaces.”

However, Rupp knows the devastation that a sweep like this one can cause. His wife, Debby Beaver, died last July in the days after they lost all their belongings and medications in a sweep.

“They wanna take everything you own and keep you moving around,” said Rupp.

OPINION: Camp sweeps have a human toll; just look at Debby Ann Beaver

Christine H., who lived in the Laurelhurst camp and requested that Street Roots not use her last name, said that the fear and confusion leading up to the sweep kept her up at night. “I can’t sleep ’cause every sound I hear I’m like, ‘Is that them? Is that them coming to take all my stuff?’” she said.

Residents noted the timing of this sweep, which came during a weeklong rain and a massive surge in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s inherently violent to displace people. You cannot do it peacefully,” said Timmi. “The timing of this sweep is just really inappropriate.”

While COVID-19 makes the sweep particularly dangerous for camp residents, it is also what enabled the camp to survive as long as it did.

Prior to the pandemic, camps were swept regularly. In a statement to Street Roots, Heather Hafer, spokesperson for the Office of Management and Finance, which oversees HUCIRP, said HUCIRP halted campsite removals following the governor’s stay-home order on March 23. That was when the city shifted its response to primarily trash removal only, Hafer said.

“We continued with cleanups and continued to respond to reports but did not reinstate campsite removals until the last week of July,” she said. “Since the last week of July, we have performed a total of 52 site removals (average is less than three a week). This is in comparison to the 40-60 campsite removals per week we were performing pre-COVID.”

Timmi, explaining the impact of COVID-19 on being houseless, said that before the pandemic, “these kind of camps would have never existed.” Timmi said that they were in a near-constant state of moving around and that they “know for a fact a lot of people weren’t homeless” before the pandemic.

This is true for Tyler Hardy. He said he had been a general contractor who owned his own business, but with the pandemic, he took a series of hits and ended up at the park.

“I came here at the beginning of the year. I couldn’t afford my apartment, so I started living out of my truck down this road,” he said. “There were people I could talk to, and so I hung around.”

Marisa Carrara and a group of friends in the northern part of the camp along Southeast Oak Street had a similar experience. Speaking amid the sweep on Nov. 19, Carrara said, “There’s like five, six of us right here in this row who lived indoors together before we were living outside. We lived together in a house, then we got illegally evicted and then wound up outside.”

Carrara, who has experienced chronic houselessness since their mid-teens, said that the camp “is probably the safest camp I’ve ever lived at. … This is the most communal, community-driven camp. This is the friendliest camp I’ve ever lived at for sure,” Carrara said.

“My belongings have been safe here. I feel my personal safety. My wellbeing, me as a person is safe here.”

This environment is no accident. In the more than eight months the camp was there, residents built a community and went to bat for one another. Carrara felt safe “because any time that I’ve gotten in any kind of trouble … I had 10 (other residents) standing behind me.

“It breaks my heart when I see girls out here that are by themselves because all I can think about is what that girl has already gone through or what she’s about to go through,” Carrara said.

Timmi, who has also experienced chronic houselessness since their teens, said they feel safer in a community.

“I feel much better if I can have a place where there are regulars,” Timmi said. “If I’m displaced and on my own, I’m at such a greater risk of so many things that I don’t even want to get into.”

Residents also described the camp protecting them from anti-houseless vigilante attacks.

“I’ve had four people jump out of a minivan and attack my elderly friend, like with masks on,” Hardy told Street Roots. He said that the community chased the attackers off.

While seemingly mundane compared to bodily safety, residents also stressed the value — both materially and psychologically — of their belongings being safe at the camp.

“I don’t have to worry about (theft or other threats) ever, period,” Carrara said, “’cause I have so many people around me all the time that constantly remind me that I’m cared about and that I’m loved and that my presence here is valued. And we all do that for each other.”

Over on Southeast 37th Street, former resident Randal Titus looked at his now-destroyed camp. “I really had it going on here,” he said. “Everyone would walk in and go ‘Whoa!’ and I’m like, ‘I know! We’re inside again!’”

Timmi, who lived at the camp for four months, also felt that the camp was home.

“Personally, the biggest positive is just having a constant spot,” Timmi said. “Constantly being displaced is part of the reason it’s so hard to get off the streets and why it’s so hard to gain any kind of routine or constant.”

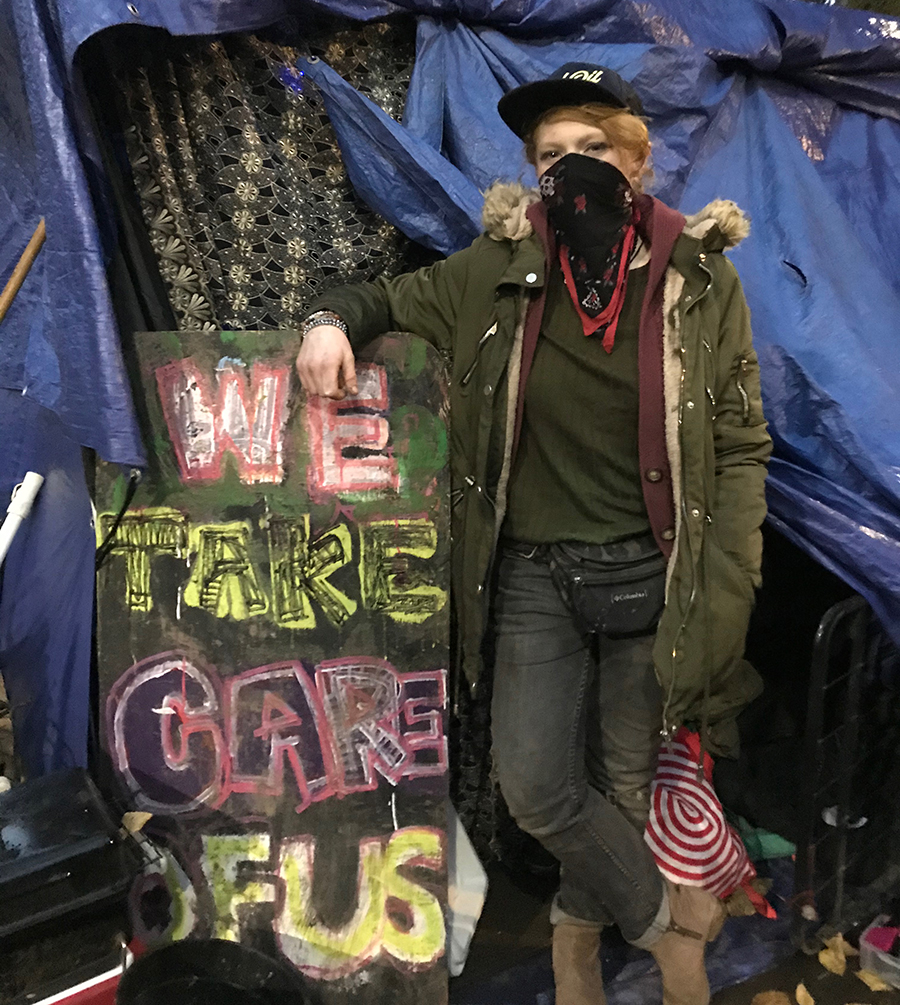

When the sweep was first announced, a network of local mutual-aid groups rallied to stop it, mobilizing, at times, hundreds of people.

And this solidarity didn’t go unnoticed by the camp residents. “The normal people trying to stop us from being swept, they moved me,” Hardy said. “They have given hope to so many people through here. … Whatever they do, little or big … is amazing.”

And for Timmi, the protesters made them feel that “there’s hope for us to be able to have long-term camps.”

When asked about the alternatives that the city provides to residents facing sweeps, all residents Street Roots spoke with said that they preferred the camp. While some cited negative experiences like violence or unsanitary conditions in shelters, many simply preferred the autonomy of camps.

Still, life at Laurelhurst presented frustrations and challenges. No resident Street Roots spoke with expressed exclusively positive sentiments of the camp.

“It’s a really difficult and complex issue happening here right now,” Timmi said, citing trash, as well as worries about addiction and mental health difficulties of fellow residents. “This community is seriously flawed, but it is community, and it feels like family.”

It is exactly because of their pride in their camp and communities that many residents were so frustrated with the trash. For Carrara, trash was the biggest issue, at times even leaving them frustrated enough to not “want to be a part of this camp anymore.”

Indeed, in Hafer’s statement to Street Roots explaining why her office ordered the sweep, she detailed the city’s timeline of events, portraying the camp’s condition with respect to trash as being non-compliant in late September and worsening from there. The statement also noted the sweep was due in part to the camp’s “high impact on neighborhood livability as well as conspicuous drug use.”

While residents acknowledged the role of trash in their eviction, many also feel the city at times uses trash as an excuse to remove them from neighborhoods where wealthy homeowners don’t want them. Carrara noted that as time passed, the camp received a decline in clean-up services from Rapid Response.

All other camp residents Street Roots spoke with said they preferred to live in clean environments.

While residents said they wanted to work with fellow campers to address the trash situation, they also said working on camp upkeep was only one part of a larger hope: Establishing long-term camps where residents can work together to meet their needs — not unlike the Laurelhurst camp, except without the looming threat of sweeps.

“People were trying, and I noticed when one person started doing good, two more people would follow,” Rush said.

Ultimately, residents expressed the desire to be housed.

“Being on the streets is going to fucking kill me in one way or another,” Timmi said. “And it should not be this way.”

The next day, as day two of the sweep drew to a close, Rush wondered where he would go next.

“I don’t know where I’m going tonight,” he said. As he spoke, a stapler could be heard approaching, four clicks at a time. The city was posting new city sweep notices, and now each tree and telephone pole through the camp served as another bright green reminder to former residents that the sweep would be finished after the weekend.

“I might just go get me a tent and, you know, start over somewhere,” Rush said. “But then it’s a revolving door. They’ll just tear that spot down.”