Many transgender people face a difficult choice.

The choice is not about which gender to identify with, as any transgender person will tell you.

The choice is whether to end their life or to live it.

The rate of suicide attempts among trans people is nine times higher than the national average. And too often in America, when a trans person chooses to live as their true self, someone else takes that life from them. More than 200 trans and gender nonconforming people have been killed since the start of 2013, according to the Human Rights Campaign, which tracks this violence. Last year was the deadliest yet, and in the first 19 weeks of this year, 23 trans and gender non-conforming people have been murdered in the U.S. and Puerto Rico. We are on track to surpass last year’s record of 44 killings, though it’s important to recognize that these numbers are artificially low because some states and reports of death only acknowledge the gender and name on a trans person’s birth certificate.

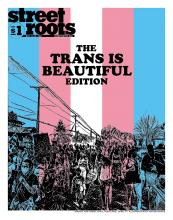

The May 19 issue of Street Roots is not only dedicated to bringing more awareness to anti-trans violence and hate, but also to what visibility truly means to people who are trans. We hope these pages will help foster an understanding among allies and within the community at large of the role Portland must play in healing trauma inflicted on the members of America’s trans community who end up at our door. We must see past the label — past the “trans” — and allow space for their diversity of talents, their passions and their personalities to shine through.

Assisting in the writing of this editorial and the creation of this edition are two trans women — two women — who both moved to Portland after fleeing parts of this country where trans people are often denied their humanity.

For Raven, coming out in Ohio meant losing nearly every friend and all her family. It meant frequent beatings with no accountability. In a state where people could justify their bigotry with laws that allow them to discriminate against and deny employment and housing to LGBTQ+ people on the basis of religion, it meant being treated as a social pariah.

For Tina, coming out in Salt Lake City was not an option. In a predominantly Mormon state, she said trans people were considered monsters. She eventually bottomed out, deciding she could not hide her true self any longer. She contemplated suicide, but decided to head for the West Coast instead.

Raven was also at a low point when she came to Portland. Originally she was just going to pass through; it was on the way to the Pacific Ocean, where she planned to end her life.

Tina’s family has since ostracized her — her father “throwing Scripture” at her when he learned her identity, but she, and Raven, has found a new family in Portland. The community here has offered them both the acceptance that they had yearned for elsewhere most their lives.

Portlanders should be proud that their city serves as a refuge for transgender people who face archaic atrocities elsewhere. Portland is a bubble in this way, but it is not impermeable, and we would be wise to not pretend that it is. On one hand, we have the responsibility as a community to recognize, talk about and confront the violence that many of our trans neighbors have fled. They may be somewhat safer now, but their trauma lives on.

A national survey in 2015 found that at some point in their lifetime, 40% of trans people attempt suicide. Compare that to the national rate of 4.6%.

And while Oregon ranked higher than most states in the Human Rights Campaign’s 2020 State Equality Index, its communities are not immune to the wave of anti-trans hatred the Republican Party is fueling. The party’s efforts were the subject of a recent episode of The New York Times podcast "The Daily." It reported that since January, more than 80 anti-trans bills have been introduced in state legislatures across our country. That’s more bills in the first quarter of 2021 than throughout the entirety of any other year in the nation’s history.

While the Biden administration reverses harmful Trump-era anti-trans policies on the federal level, people are being persecuted at the state level, and most bills are taking aim at trans youths. Many of those youths may end up in Portland after fleeing more hostile areas, and we must be prepared to love and accept them, and to offer them opportunities.

But to do so, we must recognize where we are failing transgender people right now.

Oregon has the highest statewide rate of LGBTQ+ people in the nation, with 5.6% of the population, but it also has one of the highest rates of hate crimes motivated by gender identity or sexual orientation, with 31 incidents in 2018 alone, according to a report last year from USA Today. Locally, nine specifically anti-trans incidents were reported to the Portland Police Bureau from 2017 to 2020, according to the bureau’s tracking.

While both Raven and Tina found acceptance in Oregon, they also both experienced homelessness. Even in Portland, jobs and housing don’t come as easily to transgender people as they do to cisgender people. You have to have a job to get housing; you have to have an address to get a job. We see this every day at Street Roots; at least eight (4%) of our 183 active vendors self-identify as transgender.

Raven and Tina hope the formation of a permanent, sanctioned camp or tiny-house village for trans people will offer the first step toward stability that so many trans refugees — and native Portlanders who are trans — need to survive. This camp would be different from the C3PO camp, which prioritizes all LGBTQ+ people, in that it would prioritize transgender and nonbinary people, specifically.

“When we’re together, we thrive,” explained Raven.

She is in the process of working with the nonprofit Greater Good Northwest to make this camp a reality. They have applied for grant money through Portland's alternative shelter program. As a finalist, they are now waiting to see if their plan, based on the C3PO model, is approved. Raven said it would be a place where trans and nonbinary people will be safer physically and healthier emotionally.

Previous efforts to open this camp hit a snag, however. Because the camp seeks to prioritize one group of people, a location it had originally secured fell through. Organizers are now searching for another home.

“With the last few years of violence, the trans and nonbinary communities have come closer together, and many desire to see a community where everyone there will be someone who they can talk to and support,” Raven said.

Fortunately, Tina and Raven have both found stability and housing. They first joined Street Roots as vendors but demonstrated their merit in the early days of the pandemic, helping us to organize and launch our ambassador program. Today, they are both staff at Street Roots and are dedicated to helping others find the stability they achieved.

Of the four vendors our organization was able to hire as staff this past year, three are members of the trans community. Pops, a trans man, has also contributed to this edition of the newspaper.

Street Roots’ former vendor program director, Cole Merkel, prioritized making members of Portland’s LGBTQ+ community feel welcome in our office, and he championed our annual involvement in Portland Pride celebrations. His successor, DeVon Pouncey, carries his legacy forward, and we honor it today with this edition of the newspaper.

We urge organizations and businesses across Portland to put equity, acceptance and inclusion at the forefront of their efforts. For those seeking safe haven, it can make all the difference.