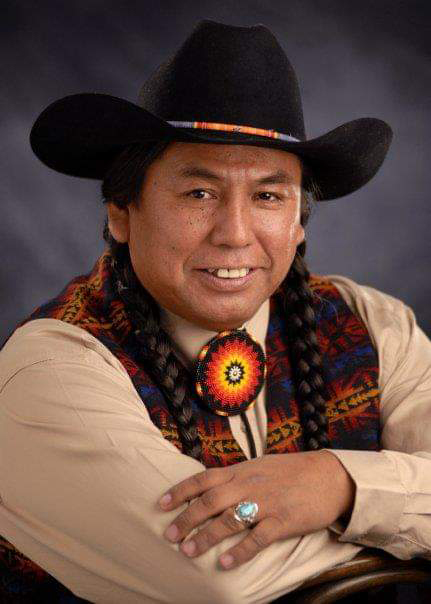

“We don’t say they died. We say that they returned home,” said Jermayne Tuckta of his tribe’s elders lost to COVID-19. “And now that they’re returning home,” he added, “some of our next generation may not know the extent of how important that language connection is.” Tuckta, an archivist at the Museum at Warm Springs, also works part time with the Culture and Heritage Department teaching the Ichishkíin language to adult learners.

When Native communities lose an elder, they lose a library. And COVID 19’s cultural toll on some communities has been high.

Despite being among the hardest hit by COVID-19, Native communities in Oregon were leaders in the vaccine rollout, some offering vaccines to the general public before they were available elsewhere.

Tuckta estimates that before 2020, there were 10 or 12 fluent speakers of the Warm Springs dialect of Ichishkíin. Now there are only four.

Why language matters

Language touches every facet of Warm Springs culture, Tuckta explained. Some elders lost during the pandemic were teaching not just vocabulary and grammar, but comprehensive spiritual walks, or ways of living, with cultural protocols rooted in Ichishkíin.

While plenty of people today are memorizing these protocols, Tuckta explained, fewer and fewer really understand them, because of language loss.

Tuckta compared the situation to singing the national anthem as a child, without really understanding the words. “We learn (protocols) as kids because we’re told to do it that way. We’re told that we have to do this before we bury somebody, we’re told we have to do this before someone got their Indian name.” He said it’s usually not until later in life that people ask why it’s done that way. And elders are the ones with that knowledge.

“They were our connection to our ancestors; they were our connection to our Creator.”

Tuckta said people not knowing the meaning behind cultural protocols is one of his biggest concerns with so many elders being called home.

“All of them believed that language was our connection to those walks of life,” he said. “They were our connection to our ancestors; they were our connection to our Creator.”

During everyday life, language is vital for interacting with sacred foods and the natural world.

Tuckta said that according to traditional stories, plants and animals were the first people in this land, before humans arrived. “When our ancestors arrived here, or were placed here by our Creator,” he said, “then they had made all of these promises in Ichishkíin to the land and to the sacred foods, and to our Creator.” Upholding and understanding those promises, and continuing their teachings, requires language retention in the community.

For example, there’s one word for Salmon, the legendary creature who was the first of the animal people to sacrifice herself for the benefit of human people, and another word for salmon, the physical fish living in the ocean or river. When the physical salmon sacrifices herself for the feast, she becomes Salmon, the legendary creature. Tuckta said you have to know your language when you say “pass the salmon” or you might end up offending an elder.

One fluent elder claimed by COVID-19 was Tuckta’s mentor, Don So-Happy, who taught him that the consequences of language loss can even extend beyond the grave. “If we don’t know our language, if we don’t have our Indian name and we can’t speak about ourselves when we leave this land,” Tuckta said, relaying his late mentor’s teaching, “this land won’t even recognize our body. Because English is not the language of this land. Ichishkíin is the language of this land.”

Another concern is how Anglo-centric culture alters Ichishkíin.

“Ichishkíin culture in general is a very direct culture, so we don’t talk about things that we have no control over, like weather,” Tuckta said. But, he said, Ichishkíin speakers have felt pressure to create ways to mimic this small talk. There’s no good translation for “how’s the weather today,” he said. “The literal translation in Ichishkíin is more like ‘what is it doing to me outside?’”

Tuckta said young people often don’t realize the importance of language and culture until they go to college or move out of state. “When we move away from the reservation we feel the absence,” he said.

In addition to the four remaining fluent speakers, Tuckta is working with “a small handful of remembered speakers,” who understand Ichishkíin when they hear it, and might speak some memorized phrases, but can’t use it to express their thoughts and feelings. Some of these remembered speakers are able to teach basic Ichishkíin, said Tuckta. “These would be elders that spoke it as children, in their childhood, and they stopped using it after the boarding school era.”

Schools for removing knowledge

In the second half of the 19th century, Indian boarding schools sought to solve the “Indian problem” by destroying Native languages and culture through assimilation. The first such school in Oregon was built by a Christian missionary in 1835, and many others followed, some of them federally funded.

Children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to live at these boarding schools. There, they were often physically and psychologically battered for speaking their languages. Not all Native children survived the boarding school era, which lasted through the 1970s. In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Languages Act, which granted Natives the right to speak their languages. Two years later, Congress updated it to provide financial support. But by some accounts, that support was too little, too late.

Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle calculated that for every dollar the United States spent eradicating Native languages, it spent only 7 cents rebuilding them.

Oregon is currently home to the oldest still-operational Indian school in the United States, Chemawa Indian School, outside of Salem. Fred Táwtalikš Hill Sr., an Umatilla Master Speaker at the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, recalls attending Chemawa in the 1970s.

By then, he said, “all the Natives that could speak their language, they were free to speak it.” There were no disciplinary measures. But by then, much of the damage had been done. “A lot of the tribes and children even then, a lot of them didn’t know their languages,” Hill said.

Those who could speak filled the halls with the sounds of Native Alaskan languages from the North, Diné (Navajo) from the south, and local languages from the Pacific Northwest.

“I was very fortunate that my grandmother, her name was Annie Jo, that she never was educated in the early education schools when they were taken away from their homes and sent out to these boarding schools,” Hill said, adding that his grandmother was born in 1883. He recalled learning how to count pennies, nickels and dimes in both Umatilla and English so he could go with her to the grocery store to interpret.

One of Annie Jo’s sons, Hill’s uncle, would write to Hill at Chemawa. In his letters, he would use the English alphabet to phonetically approximate Umatilla words. “He was instrumental,” Hill said. “He encouraged me.”

Hill would decipher his uncle’s letters and reply as best he could. “And then I’d get another letter back. He’d be telling me that I did real good and all, but at the same time he’d give me a little incentive, like a $25 money order. Yeah, back in the 70s that was some serious money,” Hill laughed.

Hill’s family narrowly escaped the destruction of the boarding school era. And today, Hill is one of only a handful of fluent Umatilla speakers remaining.

According to Chemawa’s website, the school’s mission has changed over time. Their current mission and vision are to “endeavor to preserve a safe and affirmative learning environment” while “honoring our unique tribal cultures.”

Teaching the language today

Hill teaches Umatilla language at Nixya’awii Community School in Pendleton, at Blue Mountain Community College, and at tribal community classes via Zoom. “Half the time we were running out of Zoom time,” he said, until the resource development worker created a Zoom room with unlimited time.

“We’ve been fortunate that the elders that have passed haven’t passed because of COVID,” Hill said. But that doesn’t mean there haven’t been losses, and pandemic challenges to the language program.

Katrina Miller, Program Manager at Umatilla’s Language Program, said COVID 19’s biggest impact on Umatilla language preservation was virtual. “It was a challenge for students to get online, to make sure they paid attention,” she said.

Hill added that if students don’t speak the language at home, with their parents, siblings and friends, progress is limited. “They take the class as a class, but I think once they close their notebooks that’s it,” Hill said of some students. He wants to motivate them to “talk Indian at home.”

“Don’t make it just a classroom language,” he said. “Take it outside and practice with each other.”

What happens when a language dies?

Michael Rondeau, CEO of the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians, said his great-grandparents spoke Chinook Jargon, French and English. Their ancestral language Takelma would soon be extinct, or “asleep” as Rondeau puts it.

Chinook Jargon, or Chinook Wawa, is the trading language that was used among Northwest tribes. “It has a lot of French words in it, and a lot of English words. It’s just a combination of different languages,” Rondeau explained.

“The Takelma language had basically been abandoned due to survival in the Pacific Northwest,” said Rondeau. “I don’t even believe that our ancestors in the early 1930s and 40s really thought that much about the Takelma language, because they had been trying to survive.”

And in the French-American trappers’ communities of early Oregon, that meant looking, acting and speaking as white as possible. “You had to fit in, in order to survive,” Rondeau said.

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde formally adopted Chinook Jargon as their language, seeing as tribal members come from numerous linguistic backgrounds. Cow Creek decided to revive their ancestral language instead.

In 2010, Rondeau and some colleagues took a research trip to the Smithsonian archives and began trying to revive Takelma. Their goal was to establish a dictionary and curriculum for interested tribal members. “There was never a real expectation at that point that this would be a conversational language that we would actually use in our modern day life,” Rondeau said. “We just thought that preserving it was really necessary.”

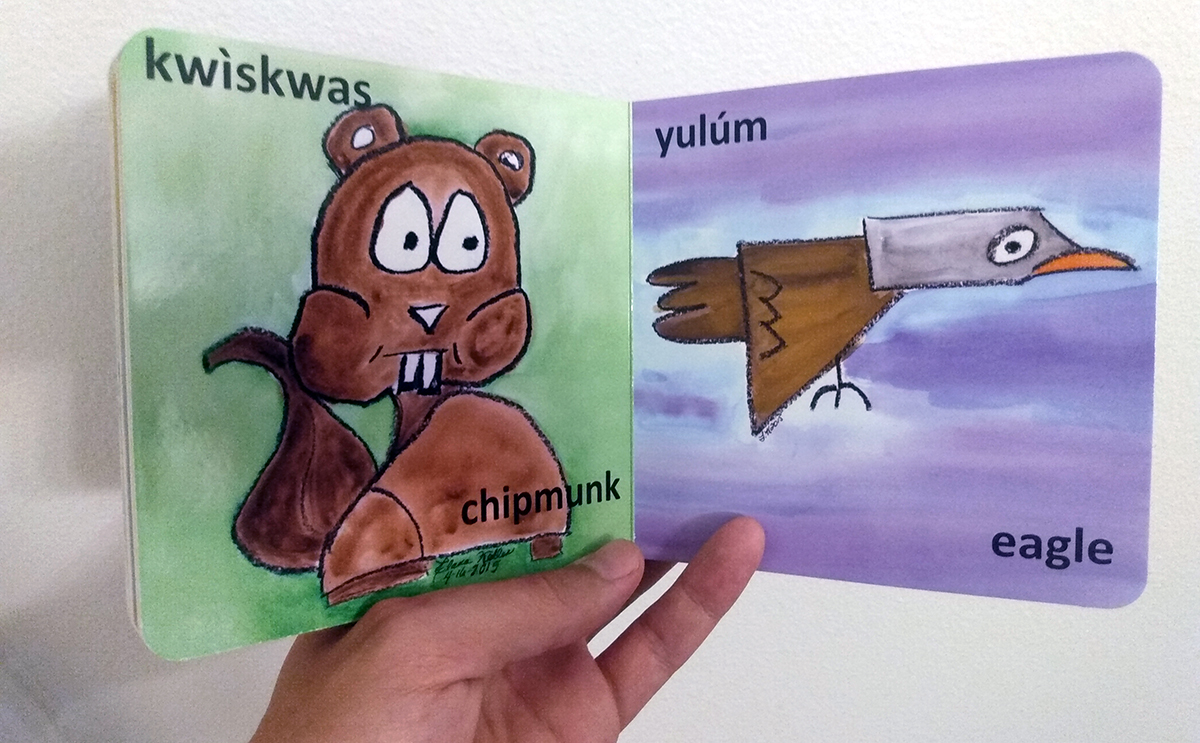

The program has been gaining momentum, and they do now have a few conversational speakers. “We are currently wrapping up our second year,” said Karissa Bent, Cow Creek’s Education Program Manager, “and there’s one more year left in our revitalization of the Takelma language.” But she added that COVID-19 had a logistical impact on their efforts, and the disruption has shown the need for more on-demand learning resources outside the classroom.

On a conference call with Rondeau and Bent, Cow Creek’s Tribal Member Liaison Rhonda Malone Richardson told Street Roots that through language research, they’ve unexpectedly recovered other knowledge as well.

“We did learn different ceremonies through our language,” she said. “We learned seasonal things, gathering, hunting, fishing,” all through language research. “Even the kids were interested. But we have lost elders, and even some of our young people,” she added.

“We had elders that were dedicated to this, and they told us how important it was to learn our language,” Richardson said, even if they didn’t become everyday speakers. One of their efforts for future generations is a language immersion program for preschoolers.

Tuckta said he considers the total loss of fluent Ichishkíin speakers to be more or less inevitable. But he’s now working with the University of Oregon on Ichishkíin grammatical examples for a new dictionary. “That way in the future, when we don’t have any fluent speakers left,” he said, “they’ll understand how the grammar works in Ichishkíin.” There’s still a chance that the language will live on, or be revived, as Takelma is at Cow Creek.

Hill noted that the Umatilla language isn’t just another school subject. “It’s who we are,” he said, adding that everything goes back to the elders. “They would get ridiculed sometimes when they spoke it,” he said. “So they endured a lot. And they just complained in the language, and cried in the language.” But they laughed in the language, too. Hill added that another important element of language preservation was “to have the humor still.”