As part of Street Roots’ ongoing solutions-based reporting on the foster care system, Street Roots took a deep dive into the national and local data on placement stability and disruptions for young people in foster care. With funding and collaboration from the Solutions Journalism Network, Street Roots searched for positive deviants, or unique programs, showing evidence of success in reducing the number of moves for kids in foster care.

Chy Nash knows how to pack a bag. The 21-year-old has carted around everything she owns in a garbage bag half her life.

Since the age of 9, Nash experienced 14 foster care placements in 11 years, including stints in foster homes, shelters, hospitals and group homes stretching from Arkansas to Oregon.

“It put me in survival mode,” said Nash, who is now living on her own in Vancouver, Washington. “I was taken away from the only thing I knew.”

Nash’s childhood home was not a happy place; she described it as “toxic, abusive in every way possible...”

But the years of packing up and moving to her next foster care placement only added to the trauma.

“After my second or third placement, I just kind-of figured no one’s going to want me anymore,” Nash said. “I just thought, this is just how it is now.”

Nash’s behavior began to change. She isolated herself and became “standoffish” to those around her.

“I didn’t want to do things that involved family activities like holidays, birthdays and movies, because I didn’t want to get attached,” Nash said.

It was a domino effect: her self-isolation caused depression, which spurred rebellion, which led to an eating disorder at 10.

“One stems from another,” she said.

Placements in family foster homes slowly gave way to longer stretches in hospitals and group homes, including one residential care facility where Nash lived with a gaggle of girls who were constantly fist-fighting over every little thing.

“Definitely a culture shock,” Nash said. “It’s a whole new world in there.”

Nash’s long slog through foster care represents one of the most significant challenges for child welfare departments across the country: how to eliminate so many moves for kids in care and create placement stability.

In Oregon, where Nash experienced multiple placements, nearly 10,000 children spent at least one day in foster care in Federal Fiscal Year 2020, according to the state’s latest Child Welfare Data Book.

The databook shows, on any given day, more than 171 youths were in group care homes, “assessment and stabilization facilities,” treatment foster care and other residential care placements. Another 67 children were receiving treatment in psychiatric care facilities.

The overall number of kids in residential treatment facilities in Oregon is down substantially from years past, but the opposite is true for annual placement stability rates. The number of kids in care with three or more placements grew to 41% in fiscal year 2020.

“When young people go into one of these centers or group homes, they can’t control what’s going to happen,” said Nash, recalling her experience bouncing from one residential care setting to the next. “There needs to be some sort of support in place to create stability in this situation that’s forever changing.”

Iowa gets innovative

Child welfare workers in Iowa were thinking about the same problem when they decided to do something radical.

They noticed that a high number of lateral moves for young people in foster care were tied to the constant shuffling of kids to different group care facilities.

Jane Harvey, division administrator for Adult, Children and Family Services at the Iowa Department of Human Services, asked a data analyst to map the moves of every foster child in the state, but the analyst gave up after just three kids.

“The map had so much kinetic energy, she couldn’t contain the data,” Harvey said. “She said it looked like popcorn kernels flying all over the state.”

Harvey’s team knew each of these moves is traumatic for kids and drives worse outcomes, so they decided they had to stop it.

They threw out the old way of doing business with group care providers and shook up the system with a sweeping new contract agreement.

Before July 2017, the state’s contracted group care providers had a lot more control over where kids were sent because they decided which children they’d serve.

“A social worker would put together an intake packet and email it to all 20 group care providers in the state,” Harvey said. “Whoever said yes first is where the child would go.”

That resulted in kids being sent to group homes all around the state, sometimes hundreds of miles away from their families, communities and schools.

“All these ways you layer on trauma,” Harvey said. “Then those moves tie into really long lengths of time in foster care, and likely, more lateral moves.”

No Eject/No Reject

State administrators decided the priority should be keeping kids close to home, so they added a controversial “No Eject/No Reject” policy to their new contract.

The policy ensures youth who need residential care will be accepted by a provider within 48 hours of a referral. No rejections.

It also restricts group home providers from kicking out kids or referring them to other group care facilities. No ejections.

At first, the changes were overwhelming for providers.

“Kids aren’t being moved around placement to placement; I agree that’s a good thing,” said Chris Koepplin, CEO of Ellipsis, a group care facility in Johnston, Iowa. “But now, without the ability to say no to an admission, it means you have to be good at everything.”

The group care providers were accustomed to specializing in certain types of care and working with other group homes to figure out the best place for kids.

“Now, whether you’re great at serving sex offenders or not, you may have to take a sex offender,” Koepplin explained. “Whether you’re great at dealing with reactive attachment disorder, or not, that’s a kid who’s coming to you no matter what.”

Harvey acknowledged the new contract caused some growing pains for providers, but the state offered them something in return: it agreed to “pre-buy” beds, in bulk, at all state-contracted group homes.

“Essentially, it used to be a fee for service,” Koepplin said. “Your occupancy rate mattered a lot in terms of how you managed your budget.”

“If you had empty beds, you got nothing,” she said.

Koepplin said the pre-purchased beds are helpful because group care providers don’t have to sell themselves as much for referrals.

“It felt very anti-mission to go to social workers and say ‘place your kids with us,’ when what we really want to do is not exist sometime down the road, right?” Koepplin said.

The state currently pays Ellipsis $195 per day for a filled bed, and $145 for an empty bed at its 48-bed suburban campus located north of Des Moines.

The state believes this steady funding stream is an incentive for group care providers to be more innovative, work more closely with families and get kids out of group care as quickly as possible.

Social workers in Iowa are now required to place kids at group homes in their own service areas. Administrators said no more “playing favorites” with group homes in other parts of the state and moving kids far from home. (Iowa has five service areas.)

“We limited the field,” Harvey said. “If we place children 300 or 400 miles away from home, we are already preventing the best predictor of whether they’re going to reunify with their families.”

Family connection proves successful

The new contract stipulates youth in group care or shelters must have a way to communicate with their families, daily.

“Just figuring out the logistics of how to make sure every kid can call their family, basically whenever they want, was an interesting conundrum,” Koepplin said.

The folks at Ellipsis eliminated “phone call days,” and replaced them with “on-request” daily phone times.

The state also set stiffer standards to ensure more in-person and virtual visits between kids and their families — efforts that Koepplin said were already underway before the contract change but weren’t as well-regulated.

“In this push toward family engagement, we’re helping the entire family, rather than just taking a kid out of his home to provide some treatment and putting him back in his home with nothing else changed,” Koepplin said, in support of the new changes.

Iowa’s child welfare leaders said the big push to keep kids close to home and reduce lateral moves between group care facilities is helping.

The Iowa Department of Human Services has reduced the number of youth in group care by nearly 50% in the past five years, and the state has become a leader in placement stability.

The contract changes went into effect in 2017, and data profiles from Iowa’s Adult, Children and Family Services show a drop in the number of moves for kids — from 3.1 moves to 2.57 moves per 1000 days in care — from 2016 to 2020.

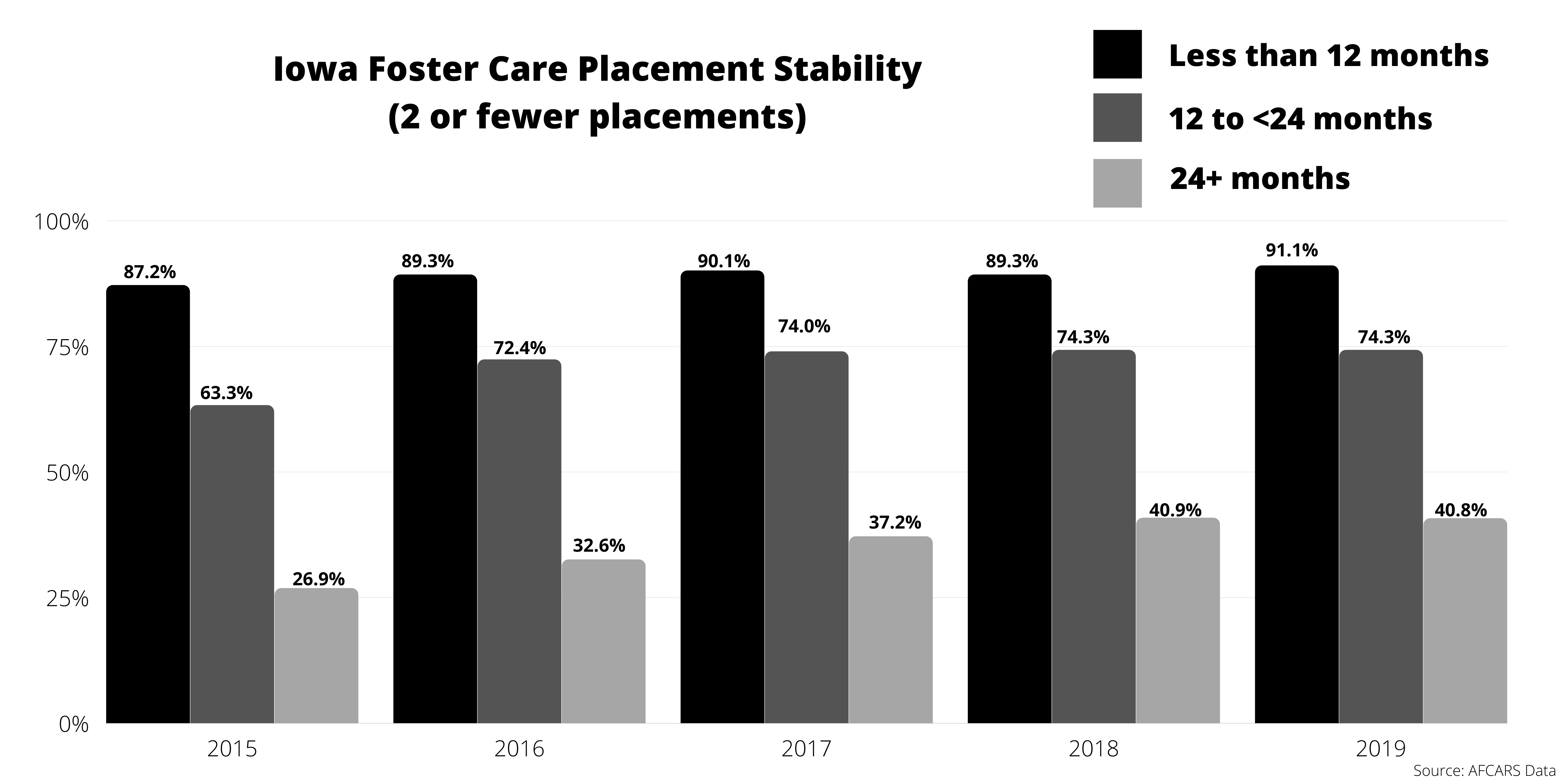

Street Roots also analyzed comparison data for all 50 states, and found Iowa consistently stood out from the pack with 74.3% of its foster youth experiencing two or fewer placements, according to 2019 data compiled by the Administration for Children and Families Children’s Bureau, from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS).

For purposes of comparison, Street Roots focused on foster youths who had been in care for at least 12 months and fewer than 24 months.

Iowa’s 74.3% placement stability trailed only Maine (77.3%,) Rhode Island (76.6%,) and West Virginia (74.5%,) but Iowa’s population is nearly four times that of Maine or Rhode Island.

Iowa also shows improvements in placement stability over time. The state made gains in all three “time in care” categories for kids from 2015 to 2019 — especially for youth in care for more than 24 months. That group’s placement stability (percentage of kids with two or fewer placements) improved from 26.9% to 40.8% (AFCARS, 2015-2019).

Working out the kinks

Group care providers believe there are a lot of benefits to the new contract agreement, including more family involvement in kids’ treatment due to an increase in parent visits and kids being placed closer to home.

But there are issues to resolve.

Koepplin, for example, said the contract’s big expectations came with big costs for group care providers who are paying for transportation related to increased face-to-face visits, staffing for filled and unfilled beds and adjustments to treatment programs.

She wholeheartedly supports new state and federal efforts to restrict residential care to children with the highest level of treatment needs, but “now every kid (in group care) is going to be super high needs, and the rates don’t match what it takes to manage that kind of a unit,” she said.

Group care providers shared their concerns with state administrators and received a bump in their pre-payments for beds in July. Providers say the increase shows state leaders are willing to work with them, but they still need more support.

Providers also believe the state’s new No Eject/No Reject policy needs more exceptions. Providers are lobbying for more sharing of services between group homes for the most difficult-to-treat youth.

“Especially with the mental health needs we’re seeing with Covid, I feel strongly about getting the right kids in the right places,” Koepplin said.

She acknowledged children might not be able to stay close to home, but they may get better treatment with a particular provider.

Harvey agreed there are some extremely complex high-needs kids and exceptions have been made, “but we make it really hard to do that, because we don’t think that’s typically the right thing to do.”

“Kids need families,” Harvey said. “For some of our most traumatized, abused and harmed kids, we seem to think it’s ok for them not to have families. I believe we just have to do better.”

Nash said we could all do better by simply listening to young people in foster care.

“I didn’t have a choice,” she said, about her experience with multiple placements. “My way was not going to happen, and that still irritates me.”

Nash is taking classes at Portland Community College and studying to become a social worker to help young people like herself find stability.

“There should be strategies and actual thoughts about each child — before placing a youth in a placement where they’re not going to thrive,” Nash said.