It is, and forever will be, one of the greatest questions that spans the sun, moon and planet, for all who’ve become parents, the question: “what do we call this child?”

Before first cradled in my mom’s arms, this great debate had already, in part, been decided by tongues long past my parents’ mouths.

The pair met in the late 1980s, a short time after my mom earned her diploma from Jefferson High School. A young Laverne Yvette Ballard was set to continue her education at the University of Oregon by way of scholarship. Instead, her grandmother demanded she get a job and start paying some bills. So rather than becoming the first in her family to become a collegiate pupil, she found a position selling Kirby vacuums door-to-door, where she met

Douglas Jordan Smith. Douglas was a suit-wearing, fake gold-donning, supposedly smooth-talking California transplant about 9 years her senior, and her supervisor.

They hit it off. For a short time at least.

For much longer in their half-decade or so together, his turmoils became rule over their relationship.

For the respect of my mother’s privacy, I’ll lean into brevity here by simply saying this: my “dad” failed her. Over and over again, before ever failing me.

In spite of this, I found my way into my mom’s womb, setting my parents to carry on in the tradition of all before them to answer that Great Question.

The finer details of their debate aren’t clear to me, but it went something like this:

My dad was best friends with a guy named Mickey. I don’t know much about Mickey, besides him being a company guy at Kirby who Doug admired. I’ve never met Mickey. I don’t even know if he is alive today. But what I do know, is that in the battle of my middle name, Mickey was conceded to my father.

Despite their turmoil, Laverne and Doug were set to become a pair of Smiths by the time I would make my grand entrance. So naturally, in the spirit of tradition, my surname would also be conceded to my father. It is worth noting here, that this union, unlike my last name, never materialized.

But it was in the battle of my first name, the one I answer to daily, the ground was not so much as conceded but rightfully seized by Ms. Ballard.

She carved out some rather simple criteria for the christening of what would be her only child: a name that was uncommon to most, and a name unshared by anyone in our immediate bloodline. After careful consideration, she finally met a crown befitting of her only son, one that would properly armor him for the battlefield of life ahead of him. She chose, Donovan meaning “dark warrior.”

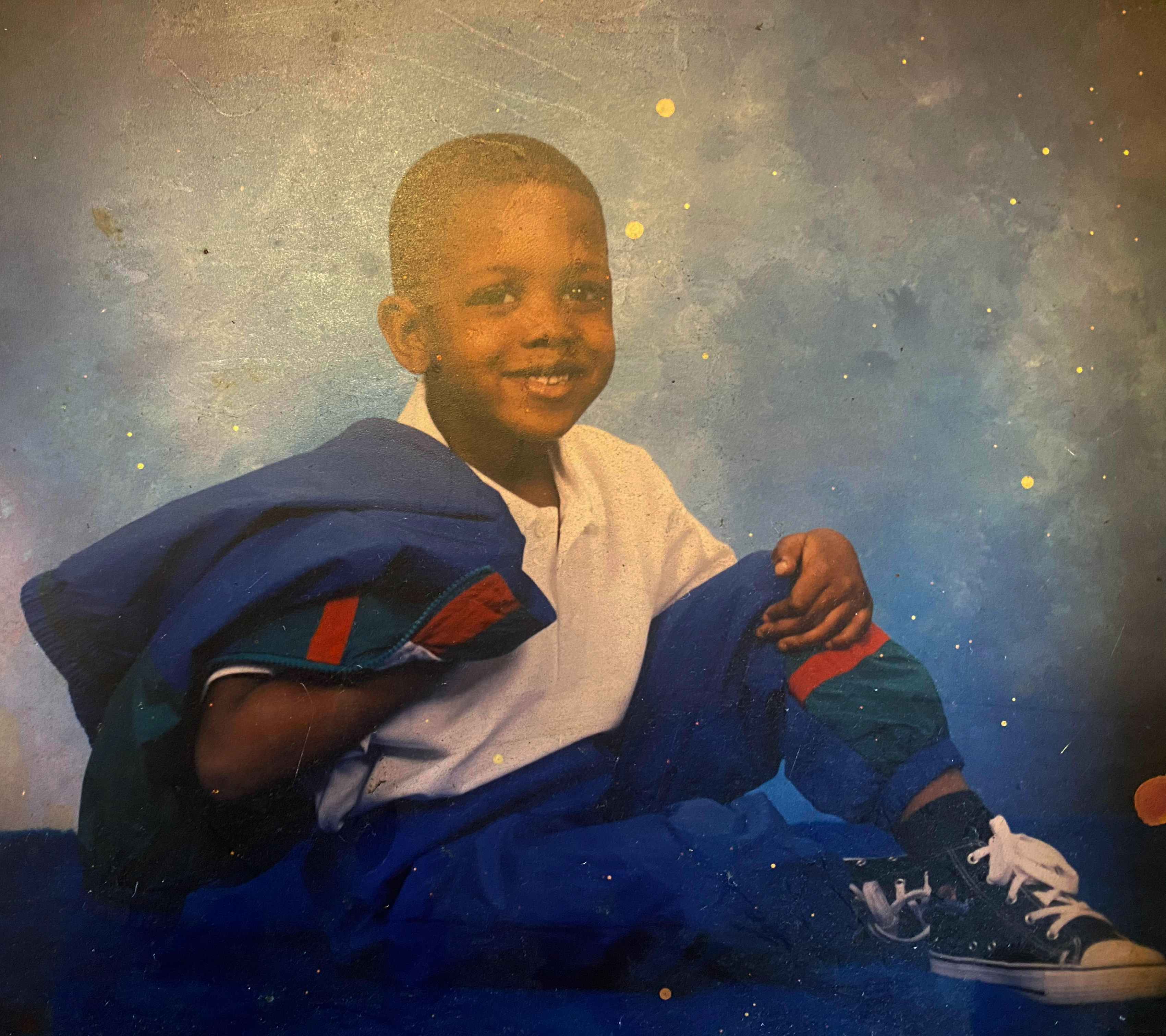

And so, the Great Question had been answered. Oct. 6, 1991, at 3:05 a.m., would meet the birth of Donovan Mickey Smith.

And so it would remain for the 30 years that followed — until now.

As you’ve undoubtedly garnered already, I’m far more favored towards one of my genetic halves than the other. The unfavored’s penchant for what I see as failure is not decoupled from a long line of traditions that have also failed him. He, unlike me, hadn’t even known who his biological father was from the womb through adulthood. It’s how he ended up with the last name Smith, when a local realtor with the last name Williams was likely his other half. He also suffered other harms I wouldn’t learn of until much later in my life, a life that he’s been a ghost of a shadow for, at best, in all my 30 years.

These harms help contextualize his trail of failures. As an adult, I have come to see his previous penchants for vices, violence and lies that veneer his evangelical and unreflective sense of grand valor, through a sort of American tradition. In that way he is average, an average American man. And while here, rests an empathy, it’s in his absolute failure to grasp even the twigs of his failings, never mind their root causes, that stunt my compassions from extending much past our shared DNA.

Despite these frailties, it was an even deeper stirring that would ultimately lead me to break from my name. An ever-dawning sense of how tradition had come to, quite unquestionably, embed itself into their names, mine and so many others that would most lead me most to chisel at my inheritance.

This story started to break light during my collegiate years. My two-year tenure began in the summer of 2010 at Fisk University which took me across the country from Portland to Nashville, Tennessee. Though leaving me without a degree, the experience left me with a greater knowing, and invaluable impressions of my once confined notions of “Blackness,” that have only expanded with the universe since.

I knew the storied bricks of Fisk were worlds removed from my home and schooling before the moment my eyes made contact with the sea of Black pupils that dotted the school’s campus and now 156-year legacy of scholarship.

The melanated, country-laden terrain, while starkly foreign, had an embrace familiar as the cradle despite its strangeness.

No longer was I “one of the Black kids,” but simply one of the others. A child of a proud tradition.

My private schooling in the privileged hills of the Oregon Episcopal School back home, while leaving my brain well-toiled, fertile and ripe with tools to question the world around me, also left me knowing, just as the sun knows the season, that my roots had foregone their necessary tending in those hills. Undoubtedly, it was here that I found great tutelage, mentorship, opportunities and parts of my brain that I flex daily, even now.

All my elementary years had been spent inside the halls of the majority chocolate, though gentrifying, Martin Luther King Jr. school. But somehow I had never been more steadily aware I was Black than at my middle and high school matriculation at OES.

Of course, it was visible. It was in yearbook photos across the porcelain that dominated the yearbooks across every decade of the school’s century existence. Audible in my teacher pointing out that I would not have been in that class a short time before while relaying the lessons of Civil Rights. Caught between the grogginess of waking up by 6:30 a.m. to trek from my mom’s first home in Montavilla to catch the city bus, to the school bus to trek to the hills where most of my peers lived on time by 8 a.m. each day.

It was deeper than these things alone though. The Teufels, owners of a local landscaping and nursery business, supplied all the greens for the school’s annual holiday sale, their name and logo plastered everywhere across Yule time. I became friends with their son Jeff. The Von Schleggels were iron-casted onto the wall for their great giving to the school. I was in class with their daughter. The math, science and technology building that birthed some of the greatest minds in the field today, became known as the Drinkward Center the year I started at OES. Their son Chad quietly passed me in the halls daily.

It was in the summer before I was enrolled here, that I learned the lesson of our names, in the high croons of subtext.

Before our first class of the year, all the sixth-grade students and their parents were invited to one of our peers’ homes, just a road away from the sprawling 59-acre campus of OES. Nicer than those I’d been in before.

"And so, I have resolved, the choice of naming, while rooted in a web of truths, is certainly worthy of scrutiny — especially for people of African descent — is ultimately a deeply personal one without any one true redress."

At the time, my mom was still the renter of a small two-bedroom apartment on NE 42nd Avenue and Sumner Street, though unbeknownst to me she was just months from owning her first home, something her parents and siblings had then yet to attain, but I digress.

In their backyard, the adults chatted as some of the boys gathered to shoot hoops.

As I awkwardly chased down a basketball I had no business handling, I had stumbled into a conversation my mom was having with another parent:

“What do you do?” the woman asked.

“I’m a bus driver,” my mom affirmed. Not mentioning the daily overtime she worked to even afford this very conversation.

“Ooooh,” the woman crooned in unfamiliarity.

And somehow, I knew that day the distance between our names and their names. But at Fisk it was different.

It was here that I was met by W.E.B. DuBois. Chiseled in bronze, his great reminder greeted the front of the campus, as a testament to the minds this side of Nashville produces. And though I wasn’t familiar with his pen then, for him to even have such note, the only statue on our centuried campus, I figured he must mean something significant for us. It was at Fisk, that I heard tales of how the Underground Railroad passed through campus centuries before as I waited in line with my mom’s sister Melissa to get my first blue-and-yellow student ID. She, just 10 years older than me, had received an offer letter from Fisk but ended up at the University of Oregon. It was at Fisk that the Civil Rights era was carved onto placards telling of how my first school’s namesake preached at our little chapel posing to them the question “What is A Man?” long before he ever shared with us his Dream.

Sadly, I never became a true Fiskite (that’s Fisk slang for a graduate of the university). By 2012, I’d been disenrolled from the school by way of some shoddy record-keeping. I often wonder what would have become of me had I become a Fiskite, though it seems fate had set me exactly into the path it had wanted. Despite leaving the school degreeless, its engulfing affirmation had quenched something I couldn’t fully articulate then but can now: My roots had been nourished.

Now, home and replenished I was tasked with how to share all my Black thoughts, with little idea of where to land them. While at Fisk, I’d been recruited to the school newspaper to pen a column, dubbed “Donspiracies” to share my thoughts on-campus life. Though I’d only written one piece there (ironically a critique on the school’s record-keeping), I found great joy in sharing my inked-out musings with my peers. After fumbling through some retail jobs, I figured I’d give writing a shot again and try to get a column at one of the state’s only two Black newspapers, The Portland Observer.

I pitched the idea, and while they didn’t need any Donspiracies, they didn’t mind having another reporter at the ready for their small weekly. My first article made it to the front page, and I figured that I may be onto something with this writing thing. I kept writing, refining and discovering that with the power of the pen my curiosities could take me pretty much anywhere. I found love.

It was around this time, the same time that I had picked up the book “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander, that the chains of my name began to ring even louder across my ears and tongue.

Her recount of the 21st-century race to profit by way of incarceration sent me racing to a new understanding of the depths of our Black plunder.

Robbed of homes, neighborhoods, schools, histories and tongues that had wrapped themselves so deeply into the very English that we were once even robbed of, that our names more often than not, were their names — what a crime.

Donovan Mickey Smith — Irish, Irish and English.

I began interrogating the very roots of my name with a scorn for all that been made of us. The deeper I dug, the greater my fury grew. “Robbed! Robbed! Robbed!” I cried.

Naturally, I sought retribution.

“What’s the most spoken language in Africa?” I demanded of my nearest Google search, not knowing where I’d been stolen from.

I found that it was Swahili and began piecing together a name that returned every piece of our bloodline that had ever been pillaged, ever concealed, ever been vanished!

I leaned into the rhythm of my name first, figuring that, at least, worth salvaging. I searched the web, looking for the perfect lyric that would send the red, black and green racing through my veins belting across the tongues of all who would ever say it. Until, finally, I found it.

To replace Donovan, I had found Asani.

Do-no-van. A-san-i.

And in Mickey, I had found Jalil.

Mick-ey. Ja-lil.

But in my surname, I found imagination.

Smith.

The most common last name in America — the UK, Australia and Canada as well — was mine. The most plain, the most White, the most owned — was mine. Its Old English meaning is “one who works in metals.” This is why you often see it attached to the names of other craftspeople: locksmith, blacksmith, or even wordsmith. Of the 2.5 million American Smiths, nearly a fifth of them are Black according to the Census. ‘Why is it so prevalent amongst us?’, you may ask. Same reason the Williams I “should” have been, Johnson, Jones, Washington and others are so domineering. Our 400-year Holocaust here has often meant taking on the names of the pillaging-class in place of ours. By the time Whiteness became institutional, and “freedom” became the game of law and order, many Blacks had assumed these cotton-bound names as a means of simple survival.

In my redefinition, I decided I could go even beyond the confines of retribution and reclamation that I had entered my assignment with, a decision that would turn to have great staying power.

My love of story has led me into some of my most fulfilling chapters. Seared into my bones lives a desire to uncover, re-examine, question and chisel at the narratives of future.

"But in reflection, I found that it is in this very English diction that I have ever expressed my cries, contentment, recollections and imaginings, including all that are laid out on this page. I know no other."

It’s been in this gift, that of documentary, that I’ve received the greatest challenge and recompense to self, family and the greater common unity.

I saw then, no better way than to break free of all molds, to don in my reimagination, that of my greatest gift, a scribe.

I looked up the name. Contrary to Smith, Scribes (I added the “s” because it sounded cooler) mostly seemed uncharted as a surname save for a handful of folks who’d lived in America in the late 1800s. A name, despite its bearing, that had little claim to it in this American land, leaving in it an opportunity. Not an opportunity to “start anew,” as we’re all just a part of the continuum, but rather “chart anew.”

Scribe is, in fact, another English word. So in some ways, it may seem contradictory to all I had originally set out to retrieve. But in reflection, I found that it is in this very English diction that I have ever expressed my cries, contentment, recollections and imaginings, including all that are laid out on this page. I know no other. The etymology of the word is Latin, as about half the others in English, and all so-called romantic languages are. It means, of course, to write. Or, more formally, according to King Webster “a copier of manuscripts.” And it was here, inside my evolving script, that I saw fit the best fashion to crown myself.

As a witness. A keeper. A griot.

A Scribes.

And so it was, Asani Jalil Scribes.

My mom hated it. Moreover, she hated Asani; not my reasoning, not even my haste. She never had cradled Asani — loved, disciplined, celebrated, stressed over Asani. Her tears poured for Donovan.

This river was not wide enough to stop me though. I rushed to the courthouse, filled out the paperwork, only to find … I was in the wrong damn courthouse. All that retribution I was seeking and imagining I’d done, and I didn’t even take the time to research where I needed to go to make the revolution happen.

I took that as a sign and stood down entirely.

Well, partially.

With time, I finally resolved that while this change was not actually the revolution I thought I had been seeking — the pursuit had at least bore some fruit. I liked how Scribes sounded on my future.

So when that Great Question finally faced me, I, at least, was partially ready.

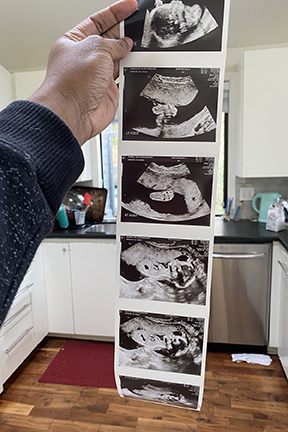

Recently my love Zoe Alexis Piliafas came to me with the greatest news. Our love had produced a little us. A little piece of the stars that we could call our own.

In learning of her pending arrival, I knew that it was finally time. My daughter would know her dad, in full, and she would know him as a Scribes.

In America, language, tradition and tongue are usually some form of gumbo. I have found, for me, it’s more important to honor my mother, and her intent and love of me as her only son by keeping the name she crowned me with, than to make an example of it. Other Dreamers understandably have decided the opposite: Stokely Carmichael found “Black Power” in Kwame Ture, JoAnne Deborah Byron unchained herself as Assata Shakur, Gloria Jean Watkins let her pen ring truths of feminity as bell hooks, Malcolm Little X’d out his last name before completely returning home in his last year on earth as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, and of course, his “blood brother” Cassius Clay had become the People’s Champ as Muhammad Ali.

Plenty of others haven’t.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois hadn’t. King hadn’t. Even Michelle Alexander hasn’t.

And so, I have resolved, the choice of naming, while rooted in a web of truths, is certainly worthy of scrutiny — especially for people of African descent — is ultimately a deeply personal one without any one true redress.

Last summer I took a DNA test. The results unearthed my now eldest-known maternal forebearer, who was born, or at least recorded to be have been born, in October 1865 as Samuel J. Ballard in Panola County, Texas. One can never be too sure of the validity of records of this era when it comes to Negro blood. I also discovered in my DNA results, unsurprisingly, another of my dad’s offspring, bringing his total known count to 13, but I digress.

Upon the discovery of Samuel, I googled alongside my mom, more about his birthplace — her dad, Nerbun, who’d migrated up from Texas in the 1960s had always told her they had strong roots in this place, but rarely expounded much past that. Panola was a slave county. Its name comes from ‘panolo’ — quite literally a Cherokee expression for cotton.

Though the Emancipation Proclamation had come into law two years prior, Samuel had been born about 245 miles from the town of Galveston, TX where enslaved Black folks had finally learned of their rightful freedom just months before his birth (this, of course, brought us Juneteenth). In the year before Texas seceded from the Union, there were 3,117 slaves in Panola County, according to the U.S. Census. That was more than a third of the county’s total population. Records from the last census before his death in 1910 show Samuel largely as a vague vignette — a Black man of the time.

Samuel couldn’t read, unlike me — nor could he write, also unlike me. He was said to be a farmer, on a farm that wasn’t his. Which begs the question, ‘who filled out this form anyway?’ But again, I digress. His mother and father, both namelessly listed, are said to have been born in Alabama and Tennessee. I cannot know for sure if Mr. Ballard was enslaved; I can infer, at the very least, he was not far removed.

It’s in this, that I am left with the wonder of my tie to this American tradition.

Wondering what made Samuel beyond these records. I do not know what became of Samuel’s cries, contentment, recollections and imaginings, what he looked like, nor anything more of what became of his days, save for his supposed death date on Nov. 2, 1918.

But, it’s in Scribes that I feel a Great Knowing. I know who decided it. I know why. I know who the next Scribes will be, and I know that I will shape all that she’ll become.

Solstice Piliafas-Scribes is set to arrive June 22, 2022, just a day after the longest sun of the year. I beam for that the day she shines her light on the world, for all to see.

And I can’t wait to witness all of her.

With love,

Donovan Scribes

Donovan Scribes is an award-winning writer, artist, speaker and producer based in Portland. A fourth-generation Oregonian, his works have appeared in iHeart Radio, Street Roots, The Oregonian and more. He’s facilitated conversations for Literary Arts & Oregon Humanities and currently serves as the 2nd Vice President of the Portland NAACP. He will be hosting a panel, “What’s a Black Name?”in collaboration with Portland State University’s Black Studies Department on a date TBD.

Editor’s note: The author preferred to capitalize the “w” in “White,” which differs from Street Roots style.