Thirty years ago, a ballot measure went before Oregon voters that has since been referred to as “one of the most comprehensive — and harshest — anti-gay measures put to voters in American history.” Sponsored by right-wing evangelical group the Oregon Citizens Alliance, or OCA, Ballot Measure 9 would amend the state constitution to prohibit "all governments in Oregon" from using money or properties to "promote, encourage or facilitate homosexuality, pedophilia, sadism or masochism." These “behaviors,” the Measure would codify as "abnormal, wrong, unnatural and perverse” and “to be discouraged and avoided."

State legislatures and voters all across the country in the 1990s were enacting new laws restricting the rights of the increasingly visible LGBTQIA+ community. Oregon came close to adopting the most regressive law in the country. During the November 1992 election, Measure 9 was defeated 56.5% to 43.5%. This is the first in a three-part series to tell the stories of some who helped win this victory.

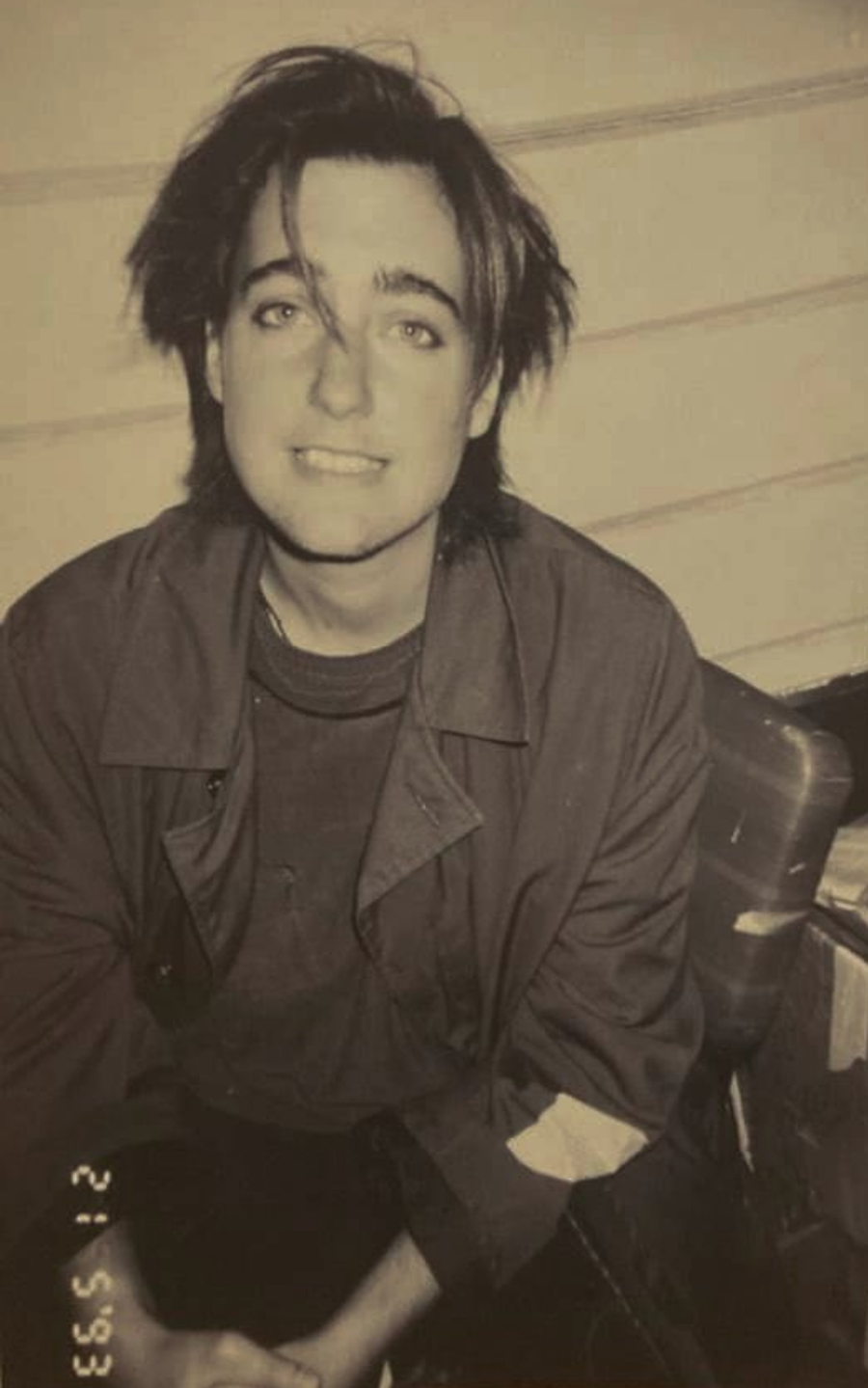

Catherine Stauffer, a queer woman radicalized in the New York City punk scene, was 21 in the fall of 1991 when she first heard about the Oregon Citizens Alliance. Inspired by the work of the Coalition for Human Dignity (CHD), she had gone with the group on a stake out of a neo-Nazi in Sellwood. The CHD started out as a city-sponsored coalition after the murder of Mulugeta Seraw in 1988 by neo-Nazis and became an independent organization when the city backed out due to liability issues. They were known among radicals for their effective tracking, harassment and pre-internet version of doxing of neo-Nazis.

It was after this experience she decided to attend meetings of anti-abortion groups to check them out “from a counter perspective.” At these meetings, she heard more and more about a ballot measure the OCA planned to file to further restrict LGBTQIA+ rights.

“It felt to me that they were getting ready to do something really dangerous,” Stauffer said.

She felt an “energy galvanizing” and intuitively felt they had a plan that might come together.

“They were trying to capitalize on homophobia at a time when we were really vulnerable,” she remembers.

The OCA was led by Scott Lively, a small business owner and transplant from California, and Lon Mabon, an “ex-hippie and Vietnam veteran.” According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the OCA had the backing of Pat Robertson's Christian Coalition, an evangelical group with a national reach pursuing “draconian and far-reaching anti-LGBT measures” on state ballots. In an article for the Oregon Historical Quarterly, “The Rise and Fall of 'No Special Rights,” William Schultz wrote conservative activists, like the OCA, viewed political conflict in war-like terms as the group declared, “we are in a mode of full-scale cultural war now.” Schultz wrote, “an essential part of this process was finding language to convince voters that they already were on the conservative side of these wars, even if they did not yet realize it.”

Groups like the OCA used slogans like “No special rights” to divide other marginalized communities, particularly the Black community. They labeled the LGBTQIA+ community as perverts, pedophiles and worse, claiming they pursued special rights undermining the hard-fought civil rights of the other, more deserving communities.

By the time the OCA filed Measure 9, Stauffer had already decided to infiltrate the group. Her goal was to blend in and gather as much information as she could to pass on to other organizations.

“At first, I really capitalized on being a young woman, who people will just talk at,” she said. “You know, men will see a young woman and … they will just talk and talk, you know, like you’re not actually a person.”

Before Measure 9

Four years earlier, before Measure 9, there was Measure 8, which was sponsored by the OCA in response to the Executive Order issued by then-Gov. Neil Goldschmidt in 1987, banning discrimination based on sexual orientation in the executive branch of state government. Measure 8 passed by a 5.4% margin, barring any state official from prohibiting discrimination against state employees based on sexual orientation. This loss was devastating to the community.

There were many complaints about the “No on 8” campaign, from it not being representative of the LGBTQIA+ community to erasure of queerness.

“‘No on 8’ … was a campaign that came together suddenly … resulting in a highly imperfect campaign structure and truncated community outreach … and then 8 passed,” Scot Nakagawa, an expert on combatting white supremacy in America, said. “And so there was a lot of blaming in the campaign leadership.”

Campaign leadership asked people not to partake publicly in the National Coming Out Day celebrations.

The belief, said Nakagawa, was that “it would trigger voter turnout for the other side … and, of course, that made people really upset.”

This time around, the opposition to the OCA sought to be more inclusive, so the newly forming “No on 9” campaign decided to hold an election for steering committee members. This is how Nakagawa found himself at the only gay bar in Eugene and an elected member of this new committee. Nakagawa was invited and elected because of his many years of effectively tracking and organizing against white nationalists, neo-Nazis and the OCA as cofounder of the CHD. He also had a record of inclusive and unity-building leadership partly demonstrated while organizing the March for Human Dignity — the largest civil rights march in the history of the Pacific Northwest at that time.

In an extensive digital history project, “No on 9 Remembered,” created for the social justice advocacy group Western States Center, Holly Pruett wrote how Nakagawa recalls that election night: “I remember it was dark. The meeting took place in the basement, which doubled as the main dance floor and bar area … the room looked just like you would expect a gay bar to look like in the light of day — a little cobbled together, stained black painted walls. Beyond that, there was the obligatory disco ball and not much else. It was very spare and felt very small, befitting a relatively small and very closeted queer community of that time.”

Nakagawa was elected along with long-time African American community leader Kathleen Saadat, founder of the Lesbian Community Project Cathy Siemens, and two Latinx community leaders.

Nakagawa eventually moved from the steering committee and joined the campaign staff as the Director of Statewide Development. The campaign spokesperson in Oregon was Ellen Lowell, a straight grandmother and leader of the Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon, who was put in that role in part to be able to make the arguments of the OCA “look ridiculous.”

“Why does a woman in the religious community who is not a lesbian want to help people who are recruiting children into becoming LGBTQ?” Nakagawa asked rhetorically.

She was instrumental in that her position was there “in order to try to isolate their argument and make the case that … (it was) actually specious,” and was “meant to scare you into taking a certain action that will have a broad and super damaging impact.” The message the campaign emphasized was that it was dangerous because “it (would) change the Oregon constitution in a way that will undermine civil rights for every single group, it will change the meaning of civil rights in the state.”

Measure 9 was “a danger to us all,” was the “No on 9” campaign’s central theme, he said, and it “would change the power balance between the government and any minority group, including evangelical Christians, so the constitution would no longer guarantee basic rights.” “You could dislike queer people, you can hate them, but if you vote for this thing the Oregon constitution will be changed in such a way that changes the power between any minority group and the government and even ideological minorities like evangelical Christians,” he said.

Meanwhile, still infiltrating the OCA, gathering information was easier than Stauffer had feared. With her willingness to work and take notes, she eventually got “offered any position I wanted on their volunteer pyramid,” she said. Originally fearing she would be caught for just appearing queer, Stauffer, she recalls, “got noticed in a way that I wasn’t expecting.”

She would pass information gathered onto various organizing groups. Despite this vital work, Stauffer never felt fully welcome by the campaign. She recalls mostly “college-educated liberals and a lot of lesbian leaders, people interested in assimilation, wanting to give awards at Pride to police officers … anyone who represented any kind of stereotype needed to be shelved … most of the time I had a beard, I was just too gender queer I think, for their liking … Middle-class acceptability was being idealized … because that's kind of what campaigns do.”

In recalling his experience during the campaign, Nakagawa reflected on how complex it all was. For him, the attacks came from all directions. He recalled being stalked and harassed by white voters; his house and car were vandalized, and he received death threats. Nakagawa said he kept the attacks to himself out of concern they would distract folks who were already frightened and had developed a “fortress” type way of thinking.

The hostility and attacks didn’t just come from voters in favor of the draconian Measure 9. Nakagawa was also targeted by groups he felt would be natural allies. Within the campaign, he recalled, “it always felt dangerous … and racist acts occurred, but parts of the campaign disagreed with it and fights occurred … over it.” It came from outside the campaign but within the movement as well, “the Lesbian Avengers, for example, the Women’s Union at PSU,” targeted Nakagawa for “basically being a political traitor.” During the Pride Parade in 1992, some of these folks followed him, and he recalls them pointing at my back yelling ‘shame!’” “And why did it happen to me and not the most powerful white people in the campaign?” he rhetorically asks. “Because they wanted my validation as a person of color, they hated the fact that the campaign had a visible person of color on staff.” According to Nakagawa, being on staff made it harder for them to “make the argument (the ‘No on 9’ campaign) just fucked us over.”

And even from his friends, “so something called ‘No on Hate’ came together that same year, ironically led by people who were friends of mine … that organization could have been complementary, but it ended up becoming oppositional because people had the singular idea of strategizing.” There was a sense among some folks, he says, that there was “only one (way) that was just and moral so it just became this really competitive and awkward situation … and this occurred on both sides, not just the community but among some in the campaign as well.”

Nakagawa was certainly not alone in dealing with the toxicity and attacks. For a long time, communities of color felt marginalized and left out of the broader LGBTQIA+ organizing community. The Asian Pacific Islanders Lesbian and Gays and the “African Americans ‘No on 9’ Campaign” were formed in response to the racism and exclusion prior to and during Measure 9. (These stories will be examined in subsequent Street Roots articles.)

The Attack

After a year of infiltrating the OCA, Stauffer began to feel leaders figured her out, so she started to pull back a little. At about this time, they invited her to the debut screening of their anti-gay campaign propaganda video. While deciding whether to take the risk of going, she recalls, “I just felt like someone was going to attack me … I envisioned someone ripping a chair from beneath me.” But she decided to go anyway, “by like a hair.”

That night, Lively called her out in front of the group of about 200 and physically attacked the young radical.

“(Lively) picked me up off the ground and threw me up against the wall, slammed me to the floor and dragged me out the front church doors and left me in the gutter,” Stauffer said.

After the attack, Stauffer remembers not having much support, certainly not from the campaign. But she pushed on. Stauffer decided to sue Lively and the OCA for assault, hoping it would negatively affect their campaign.

“The lawsuit slowed them down; it stressed them out,” she said. “We asked for like 2,000 discovery materials. That could not have been pleasant.” For Stauffer, it just became a waiting game of sorts after the lawsuit was filed. Not feeling very welcome by the campaign, she instead spent the year taking photos of protests for Just Out, Oregon’s LGBTQIA+ newspaper and painting signs out in front of her house in Southeast Portland, sometimes with the neighborhood kids, folks would pass by and take them home.

The trial was held about a month and change before Election Night. Things had become incredibly tense and scary in Oregon by that point. Tensions were high, fights were breaking out, and then, again, fears were actualized. In the late summer of 1992, queer organizers Hattie Mae Cohens and Brian Mock were murdered by racists in a firebombing in Salem. According to Pruett, “That year, the number of racist skinheads in Salem had nearly tripled over the prior year, from 23 to about 70 members.” (This story deserves a full reckoning as it was clearly documented at the time to Salem police that skinheads were targeting Cohens and Mock. For more, please see Pruett’s story on “No on 9 Remembered.”)

The violence; the murders; the fear of losing all basic rights for queer folks; this was the backdrop to Stauffer’s trial, which she described as “extremely painful and difficult."

“I felt like I was on display for all of Oregon,” Stauffer said. “The OCA’s attorney went out of his way to try to humiliate me. At one point, he made me stand up in the courtroom and turn around so that everyone could assess whether or not I looked gay.”

The bigoted antics within the courtroom weren't the only source of fear for Stauffer.

“The trial was really scary to me because I was afraid to lose, and the campaign was already looking at me like scant,” Stauffer said. “So I was afraid I would do something that would harm our side by losing. But I didn’t lose.”

Scott Lively and the OCA were ordered to pay Stauffer $31,000. However, Stauffer recalls, “the real damage I did to (the OCA) was later.”

On Tuesday, Nov. 3, 1992, Measure 9 lost by 13%. Elation and relief came first for most of those in “the family” and their allies. But many, realizing how close the vote was and in some rural counties, it was actually won, felt just as scared as before the result. They now knew for certain 43.5% of their neighbors — grocery store clerks, mechanics and teachers — all voted they should have no right to basic rights, that it was OK to codify them in Oregon constitutional law alongside pedophiles and those who practice bestiality. While elation and relief certainly happened, the victory was hard to celebrate.

After the defeat of Measure 9, Stauffer started dating Radio Slone from “The Need,” a queer punk band, and says she “had a pretty good life for a chunk of my 20s when I put it out of my mind.” The original lawsuit for Stauffer was never about the money but rather a way to stall the OCA. After the trial and Election Night, she had moved on, but by the end of the 1990s, the OCA had gained steam and was at it again.

“I just woke up one morning and was like ‘wait a second.’ I just had this intuitive sense that because I was a creditor (of the OCA who still owed her the judgment), that I could go after them really ruthlessly,” Stauffer said.

Stauffer had been living in an activist house and met Brent Foster, a radical environmental activist working with the Cascadia Forest Defenders, who was about to graduate from law school. She retained Foster, and they “mapped this out like activists.”

As creditors of the OCA, they started “draining their bank account, getting restraining orders against their (funds), calling them in for judgment debtor hearings and doing it all publicly.”

Lon Mabon, director of the OCA and his wife, Bonnie, the secretary-treasurer directed the organization to return campaign donations because, according to Stauffer, they felt, “God forbid a homosexual gets a hold of one dollar of theirs.” And then Stauffer and Foster, through the discovery materials, caught them illegally transferring funds between their corporate entities to avoid paying Stauffer.

According to Stauffer, Mabon at that point, “kind of just went off the rails” and then “couldn’t find any legal representation and started representing himself.”

“He started serving judges with papers asserting that they weren’t (as officers of the court) valid because they hadn’t taken the correct oath of office,” she said.

Eventually, Mabon got arrested in the courtroom in front of all of Oregon.

“That was just kind of his public undoing,” Stauffer said.

Stauffer remembers his booking image and him in handcuffs were all over Oregon. As an abolitionist, she recalls the feeling of this as bittersweet.

“The idea of Mabon’s public arrest being his political undoing isn’t a narrative that I particularly like, but sometimes we fight with whatever weapons we can get our hands on,” Stauffer said. “Lon Mabon was a symbol of terror to the queer community, and he had to be stopped somehow.”

Over time, the feelings of exclusion from within their own community left deep scars on folks like Stauffer.

“If (a campaign’s) primary purpose,” she continued, “is to raise funds they will always be pandering to our oppression.” However, looking back Stauffer and others have lamented waiting for the campaign to be what they wanted it to be,“It would have been great if we had more community response that wasn’t led by the campaign. That perhaps was a mistake on our part.”

Folks experienced pain from within the movement and from without. This double-edged sword is something all activists feel at some point, and some more than others. Stauffer often spoke about her lingering pain from these wounds from within "the house of a friend," a phrase she often used inspired by Sonia Sanchez's book of the same name, she equally points to how it's all more deeply rooted than that.

“Certainly, the campaign made mistakes, but I think the pain we all carry is systemic,” she said. “When marginalized groups are threatened like we were, I think the outcome is very painful.”

Nakagawa tries to put it all in perspective.

“The base of the (ballot’s) question was, ‘are these people fully human?’ People got to vote on that about us,” Nakagawa said. “And so, of course, they felt terrible, and the campaign behaved in really bad ways. I was part of the internal campaign and the dynamics were really difficult … this was a very flawed campaign.”

But, he emphasized, “we can learn from the flaws.”

Nationally recognized organizations, like Basic Rights Oregon and Rural Organizing Project, as well as the templates from the campaign used nationally, were born out of the hard work and relationships built by the "No on 9" campaign and others.

“(These templates) emerged out of these fraught dynamics,” Nakagawa said. “So, it's a complicated story. People did bad and people did good — me included.”

While individuals and smaller groups had been publicly fighting for LGBTQIA+ rights in Oregon since the 1970s, there had never been such a broad coalition among different communities and across the state as the one forged to defeat Ballot Measure 9. Essentially this coalition, and the campaign at its helm, was in its infancy while facing an extremely hate-filled, violent and vitriolic opposition they’d all never seen before.

“As a community, we were basically babies,” Nakagawa said. “Babies struggle to walk, they fall down, they cry, they shit their pants, they do all these kinds of different embarrassing and troubling things on their journey to learn how to walk.”

Nakagawa said examining the history of the “No on 9” campaign is vital to future organizing successes.

“Now the project is to pull the fragments back together again, but those fragments aren’t just bits, right, they are like pieces of glass,” Nakagawa said. “The edges are sharp. You know you're gonna get hurt in that process. Our job is to pull them back together again in some cohesive way so that the whole includes parts and the various kinds of cracks among us are sealed over in a way that doesn't make those cultural fault lines constantly available for our opponents to exploit.

“It's a bottom-up building process [that] campaigns can not build … nor should we want them to because they would fuck it up. And that’s what happened, right? People wanted (‘No on 9’) to do it but the campaign is the wrong instrument. It's like trying to do surgery with a hammer.”

Catherine Stauffer has since dedicated most of her life to doing support work for other high-risk activists. Borrowing from the Radical Mental Health Model, she is trying to build peer-supported resources for folks to heal from political trauma. Scot Nakagawa went on to work with the National LGBTQ Task Force and is now the co-founder and director of 22nd Century Initiative, a national strategy and action center that is building a movement to resist authoritarianism and preserve the possibility of a more democratic future.

Part Two will look at different communities that fought the OCA. Part Three, written by Rev. Cecil Prescod will take a deeper look at the racism many people of color faced within the movement.

Melissa Lang is a local historian and organizer in Portland.

Street Roots is an award-winning weekly investigative publication covering economic, environmental and social inequity. The newspaper is sold in Portland, Oregon, by people experiencing homelessness and/or extreme poverty as means of earning an income with dignity. Street Roots newspaper operates independently of Street Roots advocacy and is a part of the Street Roots organization. Learn more about Street Roots. Support your community newspaper by making a one-time or recurring gift today.

© 2022 Street Roots. All rights reserved. | To request permission to reuse content, email editor@streetroots.org or call 503-228-5657, ext. 404