On the concrete floor of a public restroom, inside a parking garage in Portland’s Old Town, a heroin addict took his last breaths. He was overdosing while his “street brother” pounded aggressively on the locked door that stood between them.

“I don’t know if it was stronger or if he did more than usual,” says Raymond Thornton, as he recounts his 40-year-old friend’s untimely death. He had been a couple of blocks away from the SmartPark garage on Northwest Naito Parkway and Davis Street when he heard news of the overdose. When he arrived, he saw an ambulance, “but he was already gone,” Thornton says.

This was one of 60 heroin-related deaths in Multnomah County in 2010. There would be 284 more over the next four years. All deaths where heroin is found present in the bloodstream are categorized as heroin-related deaths by the state medical examiner.

“There’s been a significant increase in heroin use in the last few years in the Portland area,” says Kim Toevs, Multnomah County Health Department harm reduction manager.

In 2014, there were 122 heroin-related deaths in Oregon, 80 of which were in Portland’s tri-county area — three fewer than the year prior, although Multnomah County’s heroin-related deaths were down significantly, from 65 to 54, according to Oregon State Police medical examiner reports.

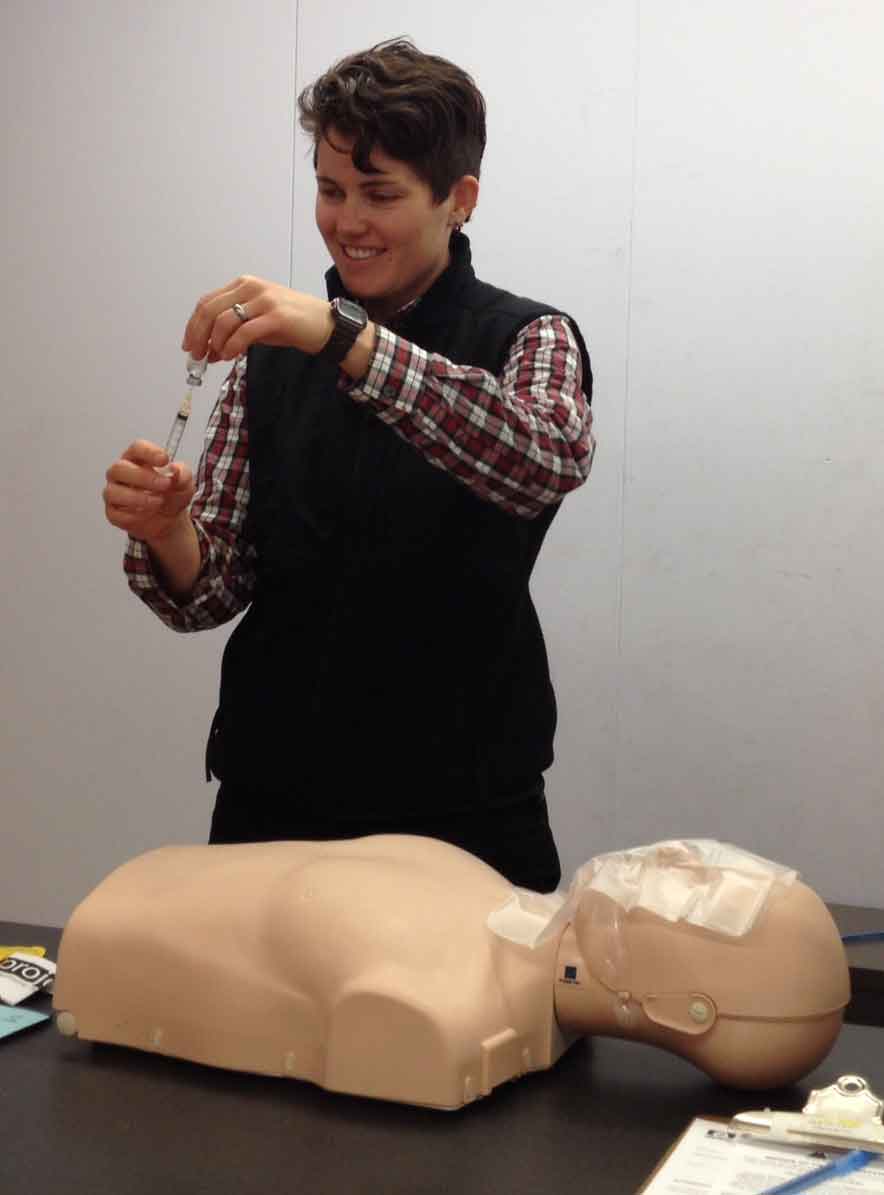

This decrease is a sign Oregon lawmakers’ 2014 move to allow for wider distribution of the overdose-reducing drug naloxone is helping reduce deaths from overdose in places where it’s available to users, Toevs says.

Naloxone is not distributed in Washington County, where heroin-related death rates have increased, or Clackamas County, where they have stayed roughly the same.

Multnomah County’s homeless popluation is hit disproportionately. While homeless individuals make up less than 1 percent of the county’s total population, they accounted for 25 percent of heroin-related deaths in 2014. A total of 57 homeless people died with heroin listed as a contributing or primary factor in their death during the past four years.

Death lurks in the shadows

Injecting unregulated drugs is risky for many reasons. The potency of the dose and nature of contaminants put into the drug by dealers and suppliers is often unknown to the user.

“Cut,” a study on contaminants found in illicit drugs by the Centre for Public Health at Liverpool John Moores University, found many adulterants manufacturers cut into heroin can cause overdose and a host of other adverse health reactions.

FROM OUR ARCHIVES: Drugs aren't the problem, Columbia researcher says

Lindsay Jenkins, Multnomah County Health Department research analyst, said taking a few days off from heroin can lower tolerance levels, increasing the chance of overdose. Being sick or run down or mixing opiates with other drugs also increases the risk of overdose, she says.

Additionally, when intravenous drug users inject in a place hidden from public view, such as in an alley or behind a dumpster, an overdose has the potential to kill them before anyone sees they’re in trouble — or before help can get to them, like Thornton’s friend.

Thornton, an ex-heroin user familiar with life on Portland’s streets, says injecting drugs with other users doesn’t necessarily make it any safer.

“So many times, people shoot up in a group and when someone can’t handle it, they just leave them there,” Thornton says. “They don’t want to get in trouble.”

The Good Samaritan Law that passed during this year’s legislative session is aimed at encouraging people to call 911 in these cases; after Jan. 1, they will be immune from prosecution when doing so.

Heroin users aren’t the only ones injecting drugs.

“The number of visits to syringe exchange sites by people who said meth was their primary drug injected has increased steadily over the last four years,” Jenkins says. However, she says that doesn’t necessarily mean more people are injecting meth. As of 2014, meth addicts accounted for 19 percent of syringe exchange users in the county.

In 2014, meth-related deaths in Oregon reached an all-time high of 166, exceeding heroin-related deaths for the second year in a row. But in Multnomah County, heroin is still a factor in more drug-related deaths than methamphetamine.

A controversial solution

The visibility of Portland’s homeless crisis and drug problem has become a point of contention with business and citizens groups pressuring City Hall to find solutions.

During a recent presentation to Mayor Charlie Hales, the North Park Block Neighbors shared photos of people injecting drugs openly in the park blocks between Northwest Eighth and Park avenues.

Public injection, whether hidden or in plain view, has also contributed to the abundance of dirty needles sprinkled around Portland, reported on repeatedly by KGW earlier this year — from failed cleanup efforts under the Burnside Bridge to needles found near playgrounds.

Many cities outside of the U.S. have discovered an effective but controversial solution that’s proved to significantly reduce the occurrence of many problems associated with injection drug use.

Now, harm-reduction advocates and drug users in several major U.S. cities are campaigning to bring this approach, known as supervised injection, to the United States.

Supervised-injection sites, also known as drug consumption rooms, have been operating in many parts of Europe since the 1980s and in Australia and Canada since the early 2000s. They offer a dedicated space for people to inject illicit drugs, which they have already obtained, under the supervision of trained medical staff who are there to intervene with life-saving measures if anything goes awry. Staff also teaches safer injection methods and offers counseling and a connection to resources when a user is ready to quit.

There are close to 100 operating supervised-injection facilities around the world.

Numerous independent, peer-reviewed studies have indicated supervised-injection sites significantly reduce deaths from overdose, increase drug-treatment enrollment among intravenous drug users and decrease rates of public drug use.

Within the first 12 weeks of opening, Vancouver, B.C.’s supervised-injection site, Insite, was independently responsible for near 50 percent reductions in public injections, improper syringe disposal and other injection related litter, according to a study by the Canadian Medical Association.

In another study of Insite, conducted four years later by the University of British Columbia and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, 23 percent of respondents stopped injecting before the study had ended and 57 percent had entered addiction treatment. Seventy-one percent indicated Insite had led to less public injecting.

FROM OUR ARCHIVES: Vancouver injection site a safe place for changing lives

According to a summary of 44 studies on supervised-injection sites put together by Ontario HIV Treatment Network, not only do supervised-injection sites reduce overdose incidence, fatality rates and injection-related disease, they also “lead to reductions in injecting behavior and an increase in the number of clients accessing addiction treatment services.”

It also found these sites “do not lead to any significant disruptions in public order or safety in the neighborhoods where they are located.”

Coming to the U.S. soon?

In August, advocates in New York City are launching a campaign and lobbying effort aimed at establishing what would be the first supervised-injection site in the U.S.

The biggest victory among supervised-injection advocates so far came in 2012 when the New Mexico Legislature approved a feasibility study on establishing a supervised-injection facility, but that effort lost momentum shortly thereafter.

Another campaign has been underway in San Francisco since 2007, and social service agencies and health departments in Boston, Los Angeles, Washington D.C. and other U.S. cities have started talking about the possibility of introducing supervised-injection facilities, as well, according to a representative for Drug Policy Alliance, a national leader in promoting drug policy reform.

“We’re sort of where syringe access was in the early days of needle exchange,” says Laura Thomas, who has been working on the campaign in San Francisco in her role as the deputy director of California’s branch of Drug Policy Alliance.

She says some San Francisco-area politicians, as well as the city attorney, have become supportive of the idea; however, “it’s continued to face the same kind of political barriers and pushback that it’s faced in other areas.”

One of the big issues driving political will to find solutions to public drug use in San Francisco is gentrification. It has brought million-dollar condos to neighborhoods that didn’t have real estate like that before, Thomas says.

“I know Portland is going through a lot of the same thing in different ways,” she says. “Some of these newer residents have expressed a lot of concern about people who are homeless, homeless encampments in the area, things like syringes being found on sidewalks and street corners, and things like that. Even though it’s not necessarily a new issue, it’s new people seeing them and complaining about them.”

She says this dynamic has pushed the issues of syringe disposal and public drug use higher on police and health departments’ agendas.

“In the next few years, we’re going to see some real breakthroughs,” Thomas says. “I think New York is taking the lead right now, but it’s a really pragmatic solution, and it’s got all the evidence behind it.”

FROM OUR ARCHIVES: 'The biggest moral issue about the war on drugs'

A documentary that premiered in Harlem, N.Y., on Aug. 25, “Everywhere But Safe,” highlights the dangers of public injecting and its effect on communities where it’s prevalent. The film’s co-directors, Taeko Frost and Matt Curtis, both work for New York City social service agencies, and they say the film is a way of educating the public and policymakers about the problems public injection poses.

It’s their hope that once people become aware, they will be more likely to support the establishment of a supervised-injection room. The film’s premiere kicked off two months of events aimed at spreading awareness and lobbying elected officials.

Curtis, the policy director at VOCAL NY, says there are no laws against supervised-injection sites in the U.S., “but there are some real questions about the gray areas of this. At the end of the day, it needs to be a place where it’s legal to possess and use drugs.

“At minimum,” he says, “you’d want an exemption of some variety from the drug laws so that a cop couldn’t walk in there and bust somebody.”

It’s important that local law enforcement is supportive so “they’re not targeting people outside and profiling people for going into the location and harassing them later,” he says.

A previous effort to establish safe rooms in New York in 2005 “trickled out,” Curtis says.

Frost, director at Washington Heights CORNER Project, which offers a syringe exchange and other harm-reduction services, sees the renewed effort as a reaction to having clients “overdose left and right” at her clinic.

“It’s really challenging to address safer injection, education and overdose effectively when it’s happening behind closed doors — whether it’s here or outside in the community,” she says. “We know that people who are injecting in public places are almost three times as likely to experience overdose in the last year.”

Curtis says another organization involved in the effort, BOOM!Health in the Bronx, surveyed small businesses with public restrooms in areas where public injection rates are high.

“A majority reported that they had encountered people using in their bathrooms, and big minorities reported customer complaints, discarded drug paraphernalia and 911 calls,” he says.

Frost and Curtis say “Everywhere But Safe” will be available to view free of charge at everywherebutsafe.org in late September.

The film was produced with the assistance of Sawbuck Productions, which made a similar film in association with San Francisco Drug Users Union in 2014, “Making a Place Called Safe,” which advocates more directly for the establishment of a supervised-injection site. It’s available for free viewing at vimeo.com.

What about Portland?

In Multnomah County, other harm-reduction methods have proved to be successful. Portland opened one of the first needle exchanges in the nation 25 years ago, helping it avoid the epidemic rates of HIV among intravenous drug users many parts of the country experienced.

FROM OUR ARCHIVES: Second chances: 25 years of Outside In’s needle exchange program

Toevs, at Multnomah County Health Department, says, “It may well be that a next step down the line would be to explore to see if a safe injection site would be appropriate for some subset of the injectors that we have in our county.”

While intravenous drug users are spread throughout the region, she says, “we have some folks injecting in a concentrated area in terms of the downtown homeless community.” It’s those concentrated areas, she says, where safe injection sites have been shown to be useful.

But, she says, “we’re not there quite yet, and I haven’t broached that with other leadership in the area to see if there’s a political willingness because my plate’s been pretty full doing a bunch of other harm-reduction interventions that we do feel like we are getting good traction on.”

She says that because of limited resources, her department doesn’t have the bandwidth to start advocating for a safe-injection site. She says doing so would take resources away from other areas of harm reduction that are having a positive impact, such as the syringe exchange, naloxone distribution programs and the Skin Care Clinic at Bud Clark Commons.

She says her department is also looking into establishing a “one-stop shopping” harm-reduction clinic on the east side of the river where intravenous drug users can obtain clean needles and naloxone and receive health care and education.

Outside In, the first agency in Portland to offer a syringe exchange and the only agency other than the county that continues to do so, declined to comment on supervised-injection sites for this story.

But would anyone use it?

Thornton, who’s been clean for five years, says he’s lost “in the neighborhood of 10” friends to heroin overdose. He believes more than half of those deaths could have been prevented if Portland had a supervised-injection site.

But would Portland’s downtown intravenous drug users take advantage of a place where medical staff would watch over them as they shot up?

“Jason,” a Portland heroin user who asked we not use his real name, says they would.

Jason has been using heroin since he was 14. Now in his early 40s, he says he frequently shoots up in public restrooms and would much rather have a clean, safe place to inject.

“I think the majority of people would,” he says. “It would keep it off the street so the average person doesn’t have to see something like that.”

According to studies of Vancouver’s Insite and the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre, clients reported they preferred to inject at the facility whenever possible.

Paul Ortiz agrees. He once had a friend die of a heroin overdose in his arms, leaving behind a wife and two teenage daughters.

“He was a nice guy, if you could get to know him,” Ortiz says.

Ortiz, who like Thornton is familiar with Portland street life, thinks intravenous drug users would “most definitely” use a supervised-injection site.

“If we can have something where people can inject, where a doctor can be there, that’d be awesome,” he says. “I was hoping they could get one here.”

Read Street Roots editorial: Portland needs safe injection site.

Latest coverage:

Safer Spaces Portland pushes for safe drug consumption site (Nov. 17, 2017)