The first time I came across vandalized humanitarian supplies in a remote part of the Sonoran Desert, I felt devastated. We’d been hiking all day to place lifesaving caches of water and beans in a corridor along the Arizona-Mexico border where hundreds of migrants die of dehydration and exposure each year.

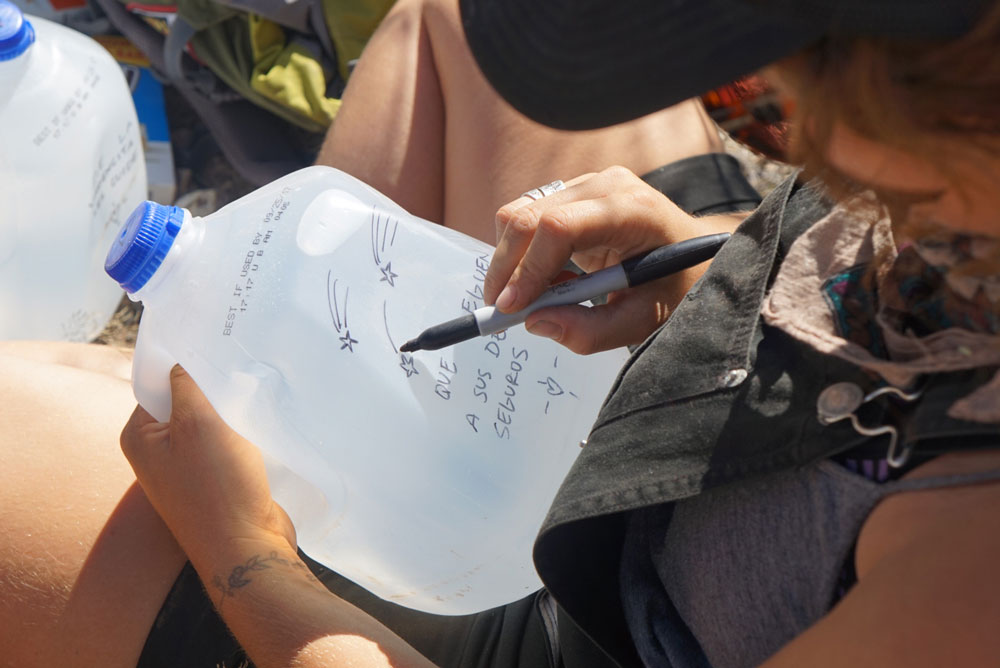

The gallons of water had been angrily slashed and kicked around, and a dozen cans of beans punctured and left to rot and stink. It looked like a tiny massacre site nestled between gnarled mesquite trees. I set down my backpack, heavy with four new gallons, and mourned quietly for this homage to humanity lost. The messages of love and hope we’d written in Spanish on the plastic jugs were cut off by jagged knife wounds – a conflicting message to whoever came across them. The slashed gallons clashed with my rosy, optimistic worldview and reminded me that my organization, No More Deaths, was not the only group acting in this desolate borderzone.

I was two weeks into the month I would spend as a desert aid volunteer with No More Deaths, a Southern Arizona-based humanitarian organization that has provided medical assistance, abuse documentation, legal aid and desert water drops for the past 12 years.

The other, more experienced volunteers on my team hardly paused at the vandalized site. This area was frequented by roving Border Patrol units who, despite efforts to rebrand themselves in a more positive light, are the most likely culprits of humanitarian aid destruction, according to the just-released “The Disappeared Report,” compiled by No More Deaths.

Over the years, the organizations logbooks have recorded hundreds of vandalized caches like this. But for each instance of heartless vandalism, there are several victorious entries of “CTFO!”– shorthand for “Cleared The F--- Out!” – when all of the water appeared to have been used by desert travelers. We wanted to quickly replenish the cache and get moving back toward our waiting pickup truck.

We take the time to write bendigas, or “blessings,” on the jugs of water. “May destinations be reached safely.”

“We’ll always keep putting out water, and not let hateful people and hateful actions prevent us from doing our work,” said Madison, 26, who moved to Tucson to be able to volunteer consistently with No More Deaths. “We don’t let destructive actions prevent us from doing our work. We take the higher road every time. It’s showing fearlessness.”

We brought the slashed bottles with us back to the old four-wheel-drive pickup we’d parked in a sandy wash a few miles away. We unwrapped bean and cheese burritos, slung our empty backpacks into the bed of the truck, and Madison navigated along the darkening dirt roads back to our desert aid station.

Hiking home

Several miles from the small bordertown of Arivaca, Ariz., the No More Deaths aid station is a ramshackle oasis built by volunteers on a shoestring budget. There’s almost no cell service, and aside from a few broken RVs for office space and a geodesic dome that houses the medical clinic, life at “Byrd Camp” is entirely outdoors.

Desert aid station kitchen: propane tanks and ice chests.

Daily chores for the handful of volunteers staying there at any given time involved hauling well water, cooking outdoors over propane burners, harvesting vegetables from a local farm, and purifying and refilling water jugs for the desert. Behind the picnic tables where we share family-style meals, a spray-painted sign reads “Humanitarian Aid Is Never A Crime” – the rallying cry of No More Deaths that had initially attracted me to their work. Medical treatment of patients who have become injured or sick while crossing the desert is legal; all of the aid provided by NMD is legally protected, and the handful of charges that have been filed against volunteers have all been successfully beaten in court – or at least the charges dropped.

'Humanitarian Aid Is Never A Crime'

It’s difficult to exactly track the number of migrant deaths in the desert each year, but the increasing deaths in this corridor are largely credited to the Border Patrol policy of “prevention through deterrence” that pushes migration towards the least hospitable stretches of desert and employs tactics such as “dusting” with helicopters to scatter groups and cause them to lose their way and each other.

A shrine created by years of migrants praying for a safe journey is tucked away into a rocky alcove.

A patient recuperating from a few days of being lost in the desert helped me chop onions for dinner, and we chatted about where he was hoping to go. “Oregon,” he said, surprising me. He had worked construction outside Portland for 15 years before going to stay with his mother while she was dying back in Nicaragua. His family still lived in Oregon, and he had been walking for several days to rejoin them. He and I shared the same awe of the Pacific Northwest and eagerness to return home. It’s impossible to think about the hordes of “rapists” and “criminals,” as characterized by Donald Trump, when you’re singing along to Latin pop and arguing over the best way to make a soup. He left the aid station sometime during the night to continue walking north in the bright moonlight.

Some nights after the dinner plates are cleared, we were left to finish card games and to journal around the table by headlamps. The solar panels and series of car batteries can’t quite keep up with the demand from a refrigerator, a few light bulbs and an array of satellite phones, GPS units and volunteers’ iPhones being charged. In October, the temperature dropped soon after the sun did, and the threat of nighttime hypothermia became an additional danger for migrants.

No More Deaths has always operated in opposition to the dominant narrative about migration flows. The organization has continued to save lives as activists, grounded in the belief that not only is humanitarian aid never a crime, but that there is a moral imperative to challenge the status quo by providing direct aid. The volunteers here have been active on the margins in ways that surprised me, an aid worker who has always functioned within the official system.

With a looming Trump presidency, I fear that much of the social justice advocacy and work done on the margins will become counter-cultural. No More Deaths has always stubbornly stood by their morals in providing lifesaving aid and solidarity in the desert despite harassment from Border Patrol.

I fell asleep in my hammock beneath the arc of the Milky Way, listening to the reassuring coyote howls echo off of the rocky hills. I hoped that whoever else was out there, walking lost under these same stars, would find the water jugs we’d left and know that someone felt that they deserved to live.

Colleen Sinsky is a former retention worker at JOIN and is currently working along the U.S. border with Mexico helping provide relief to immigrants.

No More Deaths

No More Deaths is a humanitarian-aid organization based in Southern Arizona. It formed in 2004 as a coalition of community and faith groups, dedicated to ending death and suffering in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands through civil initiative. The members deliver water, food and medical aid to those crossing through the most deadly areas of the Sonoran Desert; conduct community search and rescue for border crossers in distress; provide phone services to those who have been recently deported to Mexican border cities; and offer legal support for those in the city of Tucson who qualify for DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) or DAPA (Deferred Action for Parents of Americans) status.