When Micah was first placed in his grandparents’ care at 6 months old, all involved agreed it was in the child’s best interest.

His teenage parents were struggling with heroin addiction, which came to a head when law enforcement responded to an overdose at their Beaverton home in June 2009. Micah was camping with his grandparents that weekend, but police saw his upstairs nursery and told the young married couple that child welfare would be notified.

Not wanting their child to enter foster care, they granted temporary guardianship to his paternal grandfather and step-grandmother, Anthony and Donna Vlahovich.

The four documented the arrangement, notarized by a family member, explained Micah’s mother.

The agreement was that once Micah’s parents got their lives on track, their child would move back into their care. In the meantime, they’d remain in his life with regular visits. (“Micah” is a pseudonym to protect the child’s privacy.)

In the years since, Micah’s mother underwent a gender transformation. Today, his legal name is Lukas Soto, and he identifies as Two Spirit, a person with masculine and feminine qualities in Native culture.

What Soto couldn’t have known at the time was that once Micah was under his in-laws’ guardianship, they would do everything they could to permanently erase him from his child’s life.

IT BEGAN WHEN they petitioned Washington County Circuit Court for legal custody just weeks after Micah came into their care, and it continues to this day as they repeatedly deny Soto visitation with his son – even after repeated court orders granting him parenting time.

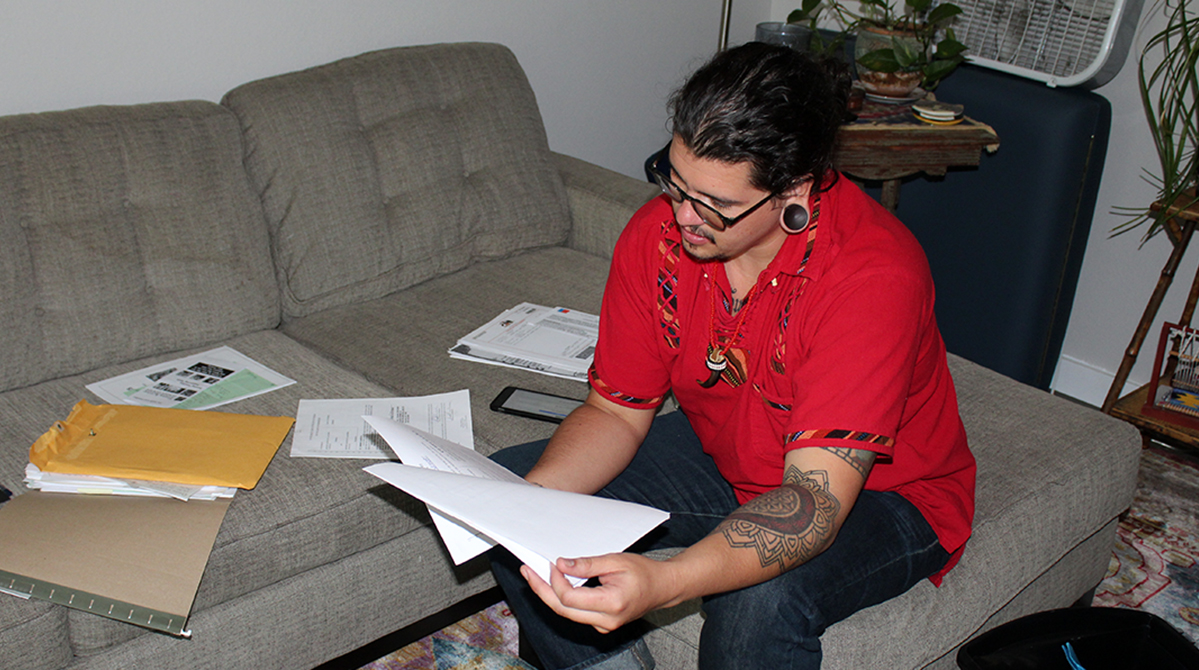

Now 28, Soto’s been clean and sober for six years. He’ll graduate with a degree in sociology from Portland State University this spring, and he has a successful career as a sustainability and racial equity consultant. He’s worked on policy with government agencies and nonprofits, as well as with sustainability directors in other major U.S. cities. He’s taken parenting classes, undergone therapy and made a new life for himself under a more fitting gender. He and Micah’s father have divorced, and Soto now lives in a newly remodeled and well-kept condo near Multnomah Village in Southwest Portland with his girlfriend, who works as a mental health and substance abuse specialist.

But all this isn’t enough to make even the most limited of visits with his son appropriate in the eyes of his former in-laws, the Vlahovichs.

“None of that has mattered,” Soto said, flipping through certificates and awards he’s earned over the years. “They’ve had it in their minds that they are doing the Lord’s work and Jesus put them in (Micah’s) life to protect him.”

But protect him from what? All evidence shows that Lukas poses no threat to Micah. Neither he nor his ex-husband ever abused their child, and Soto has proved his commitment to sobriety.

He also has a lot to offer his son, whom he views as being raised culturally as a white Christian male. He wants to teach him about his Chilean and Native American heritage. Micah is of Mapuche, Navajo and Ojibwe descent, as well as Caucasian. But most of all, he wants his son to know there is another grown-up out there who loves and supports him.

What he’s not trying to do is take custody. At this point, Micah is 10 years old and refers to his grandparents as mom and dad.

“(Micah) has been with them since he was 6 months old, so for me to be like I’m going to uproot this child out of his stability and structure, is asinine,” Soto said. “That’s never been my approach.”

Street Roots listened to hours of court hearings and examined hundreds of pages of court records, emails and other documentation related to this case. What emerged was the saga of a man who, for years, has done everything in his power to have a relationship with his son, but has been blocked at every turn by his son’s guardians.

It became clear the Vlahovichs made up their mind about Soto when he was a teenager struggling with addiction. It’s also clear his gender transformation only served to solidify their belief that he should have no role in their grandson’s life.

But Soto has never signed away his parental rights, nor were they terminated, even though holding on to them means, in recent years, he’s had to pay child support and medical bills for a child his in-laws won’t let him see.

His gender identity is an underlying theme at court hearings, with Micah’s hypothetical ability to “process” visits with his now-male mother consistently called into question by Vlahovichs’ therapist and attorney.

Micah’s grandfather continues to use female pronouns and Soto’s dead name (his name before his gender transition) when referring to him in the courtroom.

Ann Martin, the Vlahovichs’ therapist who for a while worked out of Calvary Baptist Church in Hillsboro, has testified that Micah would have trouble comprehending Soto’s gender and that the disruption of a new adult in Micah’s life would negatively impact him. Martin is a licensed clinical social worker who, when questioned on the stand about her credentials, admitted she has no experience working with transgender issues or child-parent reunification. She was hired to help Micah with behavioral issues.

Today, Micah lives west of Portland in Aloha with the Vlahovichs, who continue to ignore Soto’s pleas – and his statutory rights as Micah’s biological mother.

“My child is within arm’s reach, and there is nothing I can do,” Soto told Street Roots. “There is not a day I don’t miss my son. There is not a day my heart doesn’t hurt. There’s not a day where I am OK.”

THE LOSS OF his son is only the most recent hardship Soto has endured. He grew up poor and was often relied upon to care for a younger sibling with cerebral palsy. Physical, emotional and verbal abuse, along with witnessing his father beat his mother, were constant themes in his childhood. His father, Douglas Houk, is serving a 23-year sentence in Arizona for sexual assault of a teenager.

At age 12, Soto tried to kill himself, overdosing on Tylenol PM. He began drinking and using drugs at 15. Shortly before Micah’s conception, Soto was raped – an experience he said motivated him to sober-up at the time. He said he never used during his pregnancy.

“I was sober the whole time,” he said. “I did all the stuff I was supposed to do – didn’t eat lunch meat, no sushi, no caffeine. I very much tried to do things in the best way possible, and decided getting married was the best thing.”

Two months after Soto turned 18, he faced a new reality as a wife and mother while burdened with an accumulation of unprocessed trauma.

Upon Micah’s birth, Soto was prescribed oxycodone. He already had a history of opiate abuse, and when he could no longer refill the prescriptions, he turned to heroin.

When Micah went to live with his grandparents, Soto checked himself into Hooper Detox and Micah’s father traveled to Arizona to stay with family for a while.

It was three weeks later, while Micah’s father was still in Arizona and Soto was at an in-patient drug rehabilitation program at Providence Portland Medical Center, that Micah’s grandparents petitioned for full custody.

According to court records, both parents were subpoenaed in July 2009, but Soto said he was never hand-delivered a summons. In the end, neither parent contested the petition, and in October, after Micah was in his grandparents’ care for just four months, they were awarded full custody by default.

Soto said he wasn’t aware of the court decision until Micah’s grandfather told him about it. He went to the courthouse in Hillsboro and dug up the records, discovering it was true.

The next month, Soto was arrested for possession of marijuana and heroin and for having a fake ID for getting into bars. He was able to spend Micah’s first birthday with him but was soon after sentenced to Coffee Creek Correctional Institution, where he served 10 months.

He asked the Vlahovichs repeatedly to bring his son to Coffee Creek to see him. Finally, near the end of his sentence, they did, but only once. Anthony Vlahovich later testified in court that he and his wife decided that taking Micah to visit his mother in prison was not going to be Micah’s “story.” They made the decision then and there that they would not bring the child back to Coffee Creek.

When Soto was released, he reached out to the Vlahovichs to arrange a visit with his son. He was told it was not a good time and that they would let him know when Micah was ready. That time never came.

Soto relapsed six months later and was soon arrested on felony drug charges for a second time. This time he served nine months, with no visits from Micah.

It was around this time that Anthony Vlahovich chastised Soto’s mother for sending him photographs of Soto to share with Micah.

In an email that he sent her in December 2012, just after Micah’s third birthday, he stated he would not show Micah any photos depicting his mother.

“We treat (Micah) as our son and in doing so we are very thoughtful of whom he interacts with. This will never change,” he wrote. “We believe we were chosen by God for us to take care of (Micah).”

Four years later, the Vlahovichs would completely cut Soto’s mother out of Micah’s life as well because she showed her grandson photographs of his mother, according to text messages written by Donna Vlahovich.

Once paroled, Soto began taking hormones, beginning his gender transformation, and he finalized his divorce. He soon relapsed again and spent most of 2013 homeless, using methamphetamine and heroin.

That November, he checked himself into drug treatment for the seventh time in 3½ years. This time, he went to Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest, or NARA, and this time, he would be successful – he hasn’t relapsed since.

According to court records, Soto then reached out to the Vlahovichs to once again request a visit with his then-4-year-old son. According to the Vlahovichs’ original petition for custody, Soto was supposed to have “supervised parenting time in the child’s best interest” until he was drug free. But it had been 2½ years since he was last allowed to see his son, and he was still being denied access despite being clean.

The following August, he went to court with Micah’s father, Anthony Vlahovich Jr., who had filed a motion for parenting time. Vlahovich Jr. was in the Navy and had been visiting Micah a couple of times a year while on leave. Now he was stationed closer and wanted more frequent visits.

During his testimony, Vlahovich Jr. asked the judge that Soto be included in the parenting-time agreement. The judge said Soto needed to file his own motion.

Street Roots left messages with the Vlahovichs and Micah’s father, Vlahovich Jr., requesting interviews for this story, with no response.

In the years since, Vlahovich Jr. has been allowed regular, unsupervised visits with Micah and has established a big brother-like relationship with his son. During the court hearing that day, part of the agreement was Soto couldn’t be present during those visits.

After that, Soto began to hunt for an attorney who would take his case for a price he could afford. A newly sober convicted felon, gaining financial stability didn’t come easily. His search eventually took him to Sydney Fitzpatrick.

One of Fitzpatrick’s colleagues had put out a call through the Oregon State Bar for a family law attorney who would take Soto’s case. “Because nobody would take it. They didn’t think he had a snowball’s chance in hell,” Fitzpatrick said. “And my opinion was there’s an absolute right in the statute, and that I could get Lukas some time with his son.”

She agreed to take his case at a reduced cost.

Soto was granted his first court hearing in September 2015. Fitzpatrick asked Washington County Circuit Court Judge Kirsten Thompson to enforce a plan for supervised parenting time. At this point, it had been four years since Soto had seen his son, who was 6.

Though the length of the separation was no fault of Soto’s, it complicated matters. His attorney asked for a conservative plan involving supervised visits with the goal of working toward reunification.

Donna Vlahovich argued that due to the court proceedings, Micah was scared about his future, and she asked that reunification take place on the child’s terms.

But Judge Thompson affirmed Soto’s parental rights, and stated in her opinion that it was in Micah’s best interest to have a relationship with his biological parent. She ordered that at least one supervised visit take place before March of the following year.

“I was supposed to be having parenting time based on certain things, and it hasn’t been enforced,” Soto was heard telling the judge in an audio recording of the hearing. “How do I know, moving forward that the same thing isn’t going to happen?”

“My expectation and experience has been when people appear in front of me, under oath, that they do it. So I trust,” she replied. “If not, there are enforcement tools, and we’ll set up a review hearing to see what’s happened.”

One year later in September 2016, Soto and the Vlahovichs once again appeared before Thompson’s bench. No visit had taken place despite Soto’s efforts.

A motion for modification to parenting time that Fitzpatrick filed six months earlier had finally made it to the docket. It had been five years since Soto had seen his son.

Fitzpatrick told the judge that Soto had visited with his son’s therapist and attempted to contact the Vlahovichs.

“The (grand)parents are very clear that they are not going to allow him to see his son,” she told the judge.

This time, the Vlahovichs came to court armed with a new reason for Soto to be kept away. Their attorney argued Micah was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and slow processing, and now so much time had passed, these factors created an obstacle to reunification.

It was at this juncture the Vlahovichs’ therapist, Martin, testified to the difficulties Soto’s gender transition would pose considering Micah’s emotional instability.

She also emphasized Micah’s slow processing, but according to Micah’s actual psychological assessment, he has “low-average” processing skills – not as low as Martin and the Vlahovichs’ attorney made it out to be.

The psychiatrists who evaluated him indicated in their report that his scores in this area “demonstrate (Micah’s) current difficulties are not attributed to his reasoning abilities.”

But Martin and the Vlahovich’s attorney, James Cromar, together argued that the child’s processing abilities would make it hard for Micah to be reunified with Soto, and that Soto’s gender identity added complications.

“I’m assuming his idea of what his biological mom is, is no longer who he was envisioning the biological mom to be,” Martin testified.

She also said it wouldn’t harm Micah if he had no relationship at all with Soto.

“I’ve already lost another year,” Soto told the judge. “I was supposed to see him one time for two hours. A whole year has passed, and I don’t get that back. When is the right time?”

Soto also testified that when he met with Martin to discuss his son’s therapy, she told him that Micah was learning about what a boy was and what a girl was.

“I interjected and I said, ‘No, he’s being socialized to believe that,’” Soto said. “We’re at a day and age that we know that it’s not so black and white, and considering the complexity of the issue, the bottom line is, I’m his mom, and despite what I look like externally or my name, or any of that, he’s going to know – and how that gets told to him, I would like to do that in the least damaging way. And I’m receptive to what ever that looks like.”

WHEN IT COMES to parenting, “there is just absolutely no evidence that (gender identity) is relevant in any way,” said Shannon Minter, lead counsel in California’s landmark marriage equality case and legal director at the National Center for Lesbian Rights.

Despite that, Minter said, it’s common for a person’s transgender status to be used against them in custody and parenting disputes.

“You used to see this happen all the time with lesbian, gay and bisexual parents, losing custody,” Minter said. “Those cases rarely happen anymore. The vast majority of family courts understand that a person’s sexual orientation is not relevant to their ability to be a good parent, but we haven’t yet reached that point with transgender parents.”

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has rejected all public and private discrimination based on gender identity in parenting and adoption in an official policy statement adopted in 2009.

“Clinical experience has shown that it’s easiest for young children to understand and adjust. It can be more of a challenge for a teenage child, but even they do fine,” Minter said.

A UCLA School of Law review of 51 studies on transgender parenting found the “vast majority of transgender parents report that their relationships with their children are good or positive, including after ‘coming out’ as transgender or transitioning.”

In Soto’s case, the judge always affirmed his parental rights and upheld a plan for reunification, however conservative.

During the September 2016 hearing, Thompson ordered three supervised visits at a pace of once every three months, to be held in a therapeutic setting. After three successful visits, the frequency could be increased – if Martin, the Vlahovichs’ therapist, agreed it was a good idea.

“If this were a case where there wasn’t such a long period of time and so many other issues, I might have ordered something that was more assertive, more aggressive,” said Thompson. She also suggested the family consider open adoption.

“Sometimes the greatest gift that a biological parent can give to a child is permanence,” she said.

Again, the Vlahovichs ignored the court order, denying Soto visits for another full year.

Because the Vlahovichs weren’t following court orders, there were mechanisms Soto’s attorney could have used to enforce the court’s ruling, such as filing contempt of court and expedited parenting time enforcement motions.

But Fitzpatrick said those tactics aren’t common in every county, and she’s found them to be counterproductive. Therefore, no such motions have been filed, and the Vlahovichs haven’t seen any consequences for their actions.

At a third court hearing in September 2017, Anthony and Donna Vlahovich’s attorney, Cromar, argued that Micah began acting up in school, which they blamed on pressure related to the impending visits with Soto. He also said Soto made no effort to set up a visit.

But Soto’s attorney argued she had the emails and text messages to prove that Soto was diligent in contacting them – they were lying.

“It’s now been six years that Mr. Soto has tried to see his child and has been unable to do so,” she said. “Open adoption seems to be the only thing the Vlahovichs want to speak with my client about.”

Judge Thompson ordered visits begin that December, and every three months that followed.

Finally, a first visit was arranged under the supervision of Judith Swinney, a qualified reunification specialist, at her office.

According to Soto and emails written by Swinney, the visit went well.

Soto asked his son if he knew he was Chilean and Native American – he did. He asked if Micah had ever been to a Pow Wow – he had not. He told Micah that during their next visit, he would teach him how to make a ceremonial drum.

Soto came to that visit three months later with deer hide and other drum supplies, along with a traditional Navajo storybook to share.

“We had a wonderful visit,” said Soto. “He was completely elated; he was smiling. … When he was leaving with Judith, he kept looking back and wouldn’t put down the drum; he was excited to play it.”

But after that, things began to fall apart. Familiar arguments from the Vlahovichs and their therapist resurfaced.

Martin sent an email to Swinney saying Micah was having outbursts following the visits and they should be limited to one hour moving forward. She said during her last therapy session with Micah, he “wasn’t forth coming with what he did with Lukas, which tells me he wasn’t interested in it.”

At a hearing that June, Soto’s attorney reported Swinney was recommending visits be increased to once per month if reunification was going to work – quarterly was not frequent enough to establish a bond. The judge wanted to wait until after the third visit to make a determination.

WHEN IT CAME time for the third visit, a very different little boy arrived.

This time they met at Laurelhurst Park, and Micah seemed sullen and withdrawn.

“It was a completely changed kid. I was like, my baby is not OK, and there is literally nothing that I can do to protect him,” Soto said, his eyes welling up with tears. “Whatever it is that they are putting on him, that they are telling him, to make this happy, bright light be this disconnected sad little boy, there was nothing I could do – I can’t have this reaction,” he said, referring to his display of emotion.

In an email Donna Vlahovich sent to Soto before the visits between him and Micah began, she said Micah “has told me when I put him to bed, he is afraid to be taken away from us by his bio parents (his words) and has a hard time sleeping.” She said he uttered these words after they were making a family tree together. “We haven’t even added you to the tree yet,” she told Soto.

Soto has given Micah no reason to think he’ll be uprooted. He is not pushing for custody – even though it would be well within his rights to do so.

But he refuses to grant the adoption because he believes it would eliminate any chance he has of ever seeing Micah as long as the child is under the Vlahovichs’ roof.

“If my client were not transgendered, I can’t imagine we would be in this position,” Soto’s attorney, Fitzpatrick, told Judge Thompson during one of the many hearings. “He has done everything he can to become a productive, useful member of society, to be a good parent. … Parents have rights in this state and in this country that should not be breached.”

The last court hearing held in this case was one year ago, on Aug. 13, 2018.

The Vlahovichs’ attorney argued that Micah told his therapist he does not want any more visits with Soto but would agree to one hour every three months if an activity were involved.

“I’m concerned we’re not progressing forward very quickly in terms of contact happening more frequently,” said Judge Thompson. “It does not appear that there has been any particular harm done to the child or any violation of the supervised parenting arrangements. The report from Swinney is pretty positive. But the frequency is so limited that it would be difficult, as she indicates, ‘How can (Micah) and Lukas develop, maintain and strengthen a relationship with such limited interaction?’”

Ultimately, she ordered quarterly visits continue and said if Soto wasn’t satisfied, he could file a motion to modify the agreement.

Fitzpatrick said she filed that motion, but the hearing hasn’t been scheduled. Thompson retired, and another judge has not been assigned.

Soto hasn’t seen his son since that last visit, more than one year ago, despite his efforts to continue visitation. In all, he’s seen his son for just four hours during the past 7½ years. But he’s not giving up, despite the futility of previous court hearings.

“It’s going to take a lot more to take me out. If this is the game we’re going to play for the next eight years, then let’s do it, because I’m not backing down,” he said.

He is, however, trying other avenues. He was recently awarded a grant from the Regional Arts and Culture Council for a documentary he’s working on with local filmmaker Evan James Benally Atwood, which he hopes will draw attention to his case.

By now, if the Vlahovichs had complied with court orders, he would be having unsupervised and overnight visits with his son.

“Lukas was establishing a really good relationship with (Micah), and the grandparents just cannot leave it alone. They just won’t,” Fitzpatrick said.

Soto takes solace in the fact he was able to build a drum with his son one day, and leave him with at least a few, albeit brief, happy memories of his mother.

“The three visits I had with him,” Soto said, “I was kind, respectful, engaged and loving. Regardless of what they tell him, I have faith that he will be able to form his own truth.”

Email Senior Staff Reporter Emily Green at emily@streetroots.org. Follow her on Twitter @greenwrites.