Interlude

It was over a few grocery-store items that Billy Baggett forfeited another six years of his life.

It was dinnertime in Portland on Aug. 2, 2013, when he attempted to walk out of the Fred Meyer on Burnside Street and Northwest 20th Place with his backpack stuffed full of stolen items: a bottle of B12 vitamins, a package of deli ham, a cold sandwich, pickled pigs’ feet, socks and a couple of DVDs.

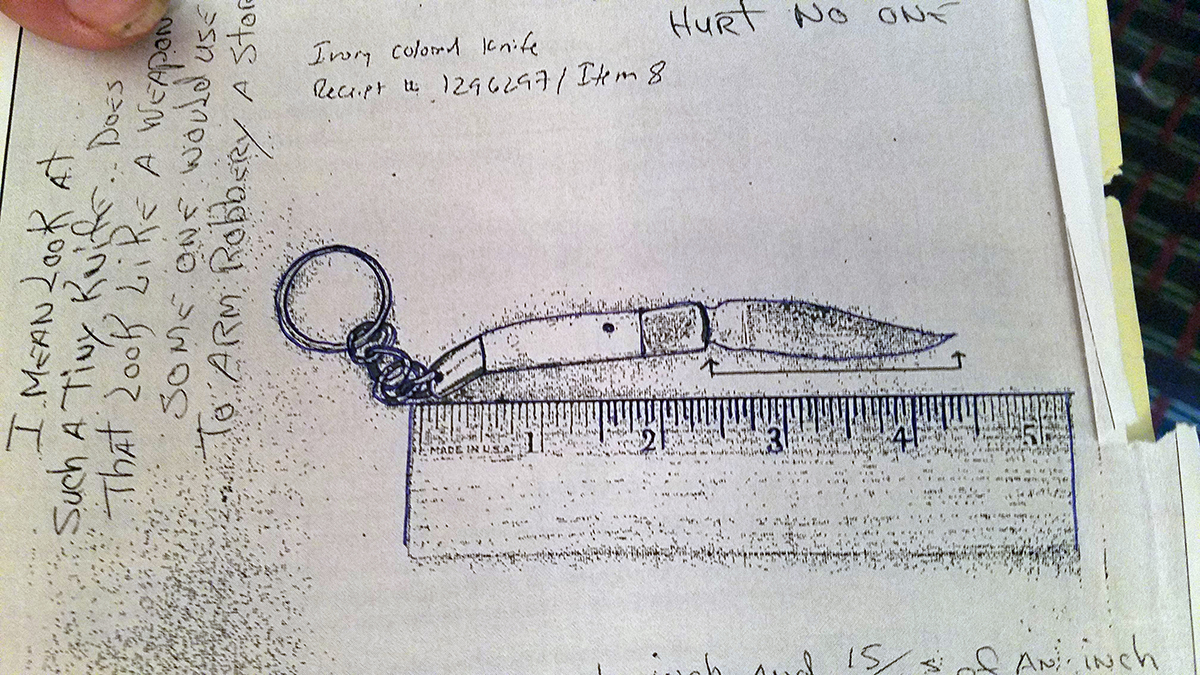

When store security grabbed hold of his pack, he panicked and pulled out a keychain pocket knife with a 2-inch blade. Then, he dropped his bag and ran.

Not knowing what to do, he ducked inside a nearby bar, the Marathon Taverna, and headed to the men’s room, where he lit a cigarette and pondered his situation.

“That’s when I found out,” he recalled jokingly, “that I must have a conscience.”

The life and death of Billy Baggett

After spending most of his life in prison, Billy Baggett was released into a world he no longer understood, contending with a lifetime of trauma and coming to terms with his imminent death.

Read the full special report.

He probably could have gotten away with it, but he returned to the grocery store minutes later to apologize for what he had done. He was promptly arrested.

“I was hoping when I came back to apologize, they would give me a job,” Baggett later said during a police interview.

He was out on parole after serving nearly four consecutive decades in prison, and this was his first misstep.

He hadn’t been able to find steady work since his release from prison, and now, after just 11 months of freedom, he was going back inside. He would have been charged with shoplifting, but when he pulled out the small knife, it elevated his crime from a misdemeanor to a felony.

Multnomah County prosecutors charged him with two counts of first-degree armed robbery, but in a plea deal, he took a conviction for felony attempted robbery instead. He was sentenced to five years and 10 months. The parole board slapped him with an extra 14 months on top of that for violating parole — all for $98 worth of groceries.

Shortly before his ill-fated shopping trip, Baggett had contemplated how returning to prison might not be his worst option.

Before being paroled the year before, in 2012, he hadn’t stepped foot outside the prison system since 1974.

Back then, Baggett was cruising around Florida in his blue 1968 Plymouth Satellite with a racing engine and gold-flaked paint he had sprayed on the vehicle himself. A flashy dresser, he often wore white patent leather zip-up ankle boots and flares — “like bell bottoms, but not as wide,” he said. He liked to cock his wide-brimmed, black-felt fedora to its side.

He remembered a gallon of gas cost about 39 cents when he pulled up to the pump, listening to Eric Clapton’s “I Shot the Sheriff” or Steely Dan on the radio.

His youth was spent largely between Thomasville, Ga., and Palatka, Fla. — small towns with fewer than 30,000 Southerners and 200 miles between them.

When Baggett decided to head west, he’d already gone through two marriages and had a string of robberies and a prison stint under his belt. Behind him, he left what he described as a blossoming career in the cocaine trade, along with the body of a fellow drug trafficker in Florida. Baggett was just 23 years old.

His recollection of life prior to incarceration was often brimming with over-the-top stories of his criminal exploits. He’d rehash detailed conversations that he’d embellished with time, and his soft blue eyes would gleam as he relived glimpses of his glory days to those who knew him in his final months.

Despite spending most his life in prisons far from home, he never lost his Southern mannerisms. His Georgian drawl was a connection to his former self — the adolescent who had not yet squandered his future.

As a much older man on parole decades later, he was known to prank social workers and medical staff, and he often employed his gentlemanly charms to flirt with nurses and people passing on the streets. He commonly broke the ice with a magic trick or sleight of hand, always starting conversations wherever he saw an opportunity.

But under all the jokes and the tall tales of times spent on the lam ran an undercurrent of trauma and exploitation that Baggett struggled to reckon with as he approached his death.

As a young man, Baggett had been in Oregon for just three weeks before he shot and killed a man outside a Portland nightclub one night in a drunken stupor.

Two convictions in 1974 — first-degree murder for the man in Portland and manslaughter for the drug trafficker in Florida — resulted in 38 straight years of incarceration, taking Baggett into some of the nation’s most brutal federal penitentiaries. He was also transferred among Nevada, Wyoming and Florida state prisons, but he served the majority of his sentences in Oregon.

While Baggett was incarcerated for taking the lives of two men, it did not appear he was a violent man in prison. He was sent to solitary confinement dozens of times over the years as punishment for disrespecting authority and contraband infractions, but he was never cited for assault or fighting. The only person he tried to kill in prison was himself, multiple times.

In 2012, Baggett was paroled at age 62. About a quarter of prisoners in his age group who were released around the same time in Oregon committed another felony within three years of getting out, despite their advanced age. That’s according to data on prisoners older than 60 who were released between 2013 and 2016 from the Oregon Department of Corrections.

Upon leaving prison, Baggett was unfamiliar with “society,” as he always called it. He no longer recognized the world around him. The culture shock Baggett experienced was far from unique.

“Some people, even if they grew up and lived in Portland before their conviction, they come out, and the MAX tracks have been laid, the whole transportation system has changed, technology, as far as phones and ATM machines,” said Brian Valetski, who works with people coming out of prison in his role at the Multnomah County Department of Community Justice.

These challenges are not limited to senior citizens. Valetski said he serves “folks in their 40s and 50s that have lower cognition, mental illness,” who come up against the same issues.

Until last year, the county offered a place where former prisoners could learn basic life skills to help them function in a technologically-driven world and get job training and education. But, due to budget cuts from the state, the county closed the Change Center.

“It’s really a shame because it really cuts what is available to P.O.s to use to support folks on probation,” said Dave Riley, Baggett’s corrections counselor with Multnomah County. “They have community service, they have electronic monitoring, and they have jail now. They don’t have other groups in-house that they can refer them to.”

The first time Baggett tried to buy a coffee, he handed 65 cents he had in his pocket to a barista at a downtown Starbucks. He was shocked to learn the beverage cost $4. He left without it.

Cars and SUVs driving past him looked like spaceships, he said. The first clunky iterations of the personal computer hadn’t even come to market when Baggett started serving his sentence. He’d never been on the internet or sent an email in his life. It was like walking onto the set of a sci-fi movie.

Baggett had changed, too. The once reckless and often inebriated youth who committed murder in the disco era was now a 62-year-old man trying to start fresh. An entire lifetime inside the walls of prison complexes separated him from his former self.

Inside the penal system, as much as it had brutalized him, Baggett had figured out how to survive, and he knew what to expect. Outside, he felt helpless.

But he was not without help. He was housed in a subsidized apartment inside the Central City Concern’s Henry Building in downtown Portland, and caseworkers assisted him in the long process of attempting to secure Social Security benefits — he never got a check before going back to prison — and they signed him up for Medicaid, which was much needed given his significant health needs.

When he was incarcerated, he picked up heroin and methamphetamine, injecting the drugs for many years; he smoked cigarettes and cannabis for decades; and he ate the notoriously subpar food that’s served to prisoners most his life. He contracted HIV in a Florida prison in 2005. By the time he was released in 2012, it had been more than a decade since he last used hard drugs, but his body was starting to fall apart. His progressive lung disease, COPD, worsened when he picked up smoking again as a free man. But poor health and premature death are common among America’s prisoners.

Research analysis from the Prison Policy Initiative spells out the health impacts of incarceration. It found that with millions of Americans behind bars, mass incarceration has taken five years off the overall average U.S. life expectancy. It also points to nutritionally inadequate prison food and the risks associated with solitary confinement as detrimental to prisoners’ health long after their release.

Further encumbering people released from prison is the isolation that extends from their incarceration into the world outside. This was true for Baggett.

Aside from a cousin who lived in Portland, Larry Baggett, he was alone. Both his parents and his younger brother died while he was incarcerated, leaving him with one remaining sibling, a sister in Thomasville, Ga. She told Street Roots she has no memory of her brother before his imprisonment. Baggett said he asked her once during a phone call if she loved him, and she responded that she barely knew who he was. It broke his heart.

Despite their distance, she had offered to let him come live in a trailer on her property, and for a while, he tried to find a way to get back to Thomasville. But, the travel costs and limitations of his supervision stood firmly in the way of his return. He got discouraged and decided to stay in Portland where he knew his medical needs would be met. He was also against wearing an electronic monitoring device, a requirement if he moved out of state. He served his time, he told his sister. He wanted freedom.

“People with family are far more successful than those without,” Valetski said, noting that despite Baggett’s lack of close familial connections, he was lucky to be released in a metro area. “The rural counties in Oregon have far less resources than we do.”

Baggett had food stamps, but no money, and the fines he owed to the state of Florida, along with the supervision fees he had to pay Multnomah County, weighed heavily on him as they stacked up, according to his counselor’s file notes.

He found that even though he was free, many comforts he’d missed behind bars were still equally out of reach. He craved his favorite food, fried chicken. But even a meal at KFC was above his means. He felt like an outsider, unable to dine at restaurants or pay for a ticket to the movies.

Baggett knew from the outset of his release that he wasn’t in for an easy life. Despite the apartment and food assistance, he felt like he didn’t have the support he needed to be successful in his transition, and he expressed these fears to the people supervising his parole.

A Multnomah County parole officer typed into Baggett’s file that he was “completely OVERWHELMED AND FRIGHTENED (capitalization theirs) due to being incarcerated for 38 yrs.”

It was also noted he didn’t know how to cook or take the bus, and that despite his many ailments, Baggett was denied Social Security disability benefits. He was given some bus passes and a booklet that listed local resources for low-income people. As the months passed, it was entered into Baggett’s file repeatedly that his health was deteriorating and he was feeling increasingly isolated.

“Everywhere I tried to look for a job, they turned me down,” he said. “I was too old, my health was too bad, and I had a prison record, and they didn’t want to hire me. I couldn’t even get a job washing dishes.”

But Baggett knew how to hustle. He began hanging around outside Club Rouge, a strip club a few blocks from where he was living. He ran errands for dancers while they were on shift. He might pick up a pack of cigarettes or other items they requested. He swept the sidewalk in front of the club. Sometimes he’d watch the club owner’s car. It wasn’t close to a paycheck, just $30 or $40 a night, but it gave him a little cash to spend.

“I think as long as Larry was alive, Billy did pretty good,” Baggett’s sister, DeAnne Harrell, said of their cousin who lived in Portland. “But after Larry died, he kinda flipped off the deep end.”

Larry Baggett died in January 2013.

It was during the summer following his cousin’s death that Baggett decided he was willing to risk his freedom for a few groceries. He thought he no longer cared whether he was outside of prison. While the sentiment was fleeting, his impulsiveness meant he’d spend the majority of the time he had left back inside.

In 2019, Baggett was nearing the end of the sentence he earned for robbing Fred Meyer. Now confined to a wheelchair, he spent most of his time on the bottom bunk in his 8-foot by 10-foot cell, watching his 9-inch television. Sometimes he’d illustrate cards that other prisoners would send to their loved ones.

About three years earlier, Dr. Garh Gulick at Snake River Correctional Institution in Eastern Oregon diagnosed him with congestive heart failure.

“He said, ‘You’re not going to live very much longer, but I’m going to turn in a letter to the DOC health department to tell them it would be more humane to allow you to die in society rather than have to die in prison.”

Baggett also had blood clots in his thighs. He had edema — fluid retention in his legs and around his heart — and his kidneys were beginning to fail. While he had managed to keep his HIV at bay, his COPD had entered its final stage, and he often required an oxygen tank. Even the smallest task, such as getting up to use the bathroom, rendered him breathless.

Baggett said his health was so dire that Gulick recommended his early release.

“He said, ‘You’re not going to live very much longer, but I’m going to turn in a letter to the DOC health department to tell them it would be more humane to allow you to die in society rather than have to die in prison,’” Baggett recalled.

He was able to get the 14 months he received for violating parole shaved off his sentence. If not for that, he would have died behind bars.

“Our population is aging in prison, and typically, they’re looking to release them,” said Valetski, who supervised Baggett’s parole officer. “This has been an ongoing issue for many years now.”

That year, Baggett was one of 192 prisoners age 60 or older Oregon Department of Corrections released. A department spokesperson said the agency could not say how many of those prisoners were chronically ill. The same year, 26 prisoners age 60 or older died in custody.

In New York, where older prisoners make up about 20% of the prison population, a bill introduced in the state Senate would afford prisoners age 55 and older who have served 15 years of their sentences a hearing to determine if they can be released to community supervision. The Elder Parole Bill, as it’s known, passed out of the Senate Crime Committee in April 2019.

Determined not to fail at freedom again, Baggett began preparing for his reintroduction to society months in advance. He contacted a charity in Orange, Calif., Wheels of Mercy, which agreed to send him a free motorized scooter he could use once he got out. His COPD made it nearly impossible to wheel himself around in the DOC-provided manual wheelchair. He requested multiple times to be transferred to Columbia River Correctional Facility where he might be offered some transitional assistance, but he changed his mind when he discovered a prisoner he had beef with was housed there.

Most people coming out of prison do not possess Baggett’s resourcefulness, his caseworkers said. In many cases, that means they get less help. But despite all of Baggett’s efforts, the system isn’t designed to meet the needs of aging prisoners with medical issues when they’re released.

The morning of May 31, 2019, as Baggett wheeled out of prison, familiar fears and anxieties returned. Only this time, he faced old feelings of inadequacy while also contending with his mortality.

There is no reentry facility with skilled nursing staff, so Baggett was placed on the third floor of Portland’s Hotel Alder, which serves as reentry housing for older people coming out of prison.

That’s where I first met Baggett in person, just hours after he arrived in Portland following his release.

He was a heavy-set senior, sparsely covered in crude, black-ink prison tattoos and wearing a striped polo shirt and khakis that were provided to him as he exited the penitentiary; he had no other clothes. Preferring to wear black, the outfit made him feel like a clown, he later said. His long, straight gray hair was tied back in a ponytail at the nape of his neck and extended down past the middle of his back. He wore cheap glasses, the prescription so old they barely helped his vision.

It quickly became apparent, as someone once wrote in his prison file, that he “presented as a polite Southern gentleman.”

He was in good spirits, telling cornball jokes to county staff as he clumsily maneuvered his new scooter.

He was initially quite happy with his room. It was larger than most, to accommodate his wheelchair, and included some shelving, a twin-size bed with one sheet tied in a knot at its end so that it functioned as a fitted mattress cover — just like they do in prison, said Baggett. There was a microwave he didn’t know how to use, a fridge, a table and a chair.

His first day out, the Hotel Alder’s site manager escorted Baggett around downtown as he signed up for health care coverage, an Oregon Trail food benefits card and Social Security payments. He was given a few Goodwill vouchers and bus passes.

His release was on the last day of the month, and it was a Friday. Anyone whose sentence ends on a weekend gets out the Friday before, making Fridays the busiest day of the week for reentry. This creates a headache for social workers, forcing them to scramble to get benefits lined up for their clients before the weekend.

Riley, Baggett’s county-provided corrections counselor, specializes in working with those released with medical and developmental disabilities. He said it was imperative that Billy got his Social Security payments rolling the day he got out.

“You don’t get paid for the first month you get out; you get paid for that next month,” he said. That meant that if Billy didn’t get signed up that day, he would go through the entire month of June without benefits.

After signing packet after packet at the county’s Aging and Disabilities office, the Hotel Alder site manager walked with Billy to get some clothes, dishes and other basic items from Central City Concern’s clothes pantry in Old Town.

Baggett took a couple of used shirts, pants — the only pair in his size — socks and towels, along with an extra pillow, some dishes and a baseball hat. He turned down the offer of second-hand tighty-whities.

He would use his food-stamps card for underwear; now that he was over the age of 65, the Oregon Trail card worked as a debit card, too. He would get $182 a month to spend on food and other items. He also had $42 he’d saved from his time in prison.

His first night at Hotel Alder was quiet. Sleeping in the dark for the first time in many years was unfamiliar.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” Baggett said of his first evening out of prison. “Kinda scared to just come out of the building. I didn’t know where to go. So I pretty much stayed outside the door there, watched the cars go by and the people go by, and stayed in my room. Just that night. The next day I started trying to get around a few blocks, see what stores looked like, looking at different people and all, watching pretty girls go by. But it’s all strange. It’s like an alien world in a lot of ways. All my life, I seen the world through a window called television, and that’s the only thing I know.”

While a doctor at the Multnomah County Health Department gave Baggett a medical marijuana card, he was not allowed to use cannabis while living at the Hotel Alder.

“They get federal funding, and it’s still illegal federally,” Riley explained. “It is frustrating. I would love to see us have another way to do that.” But, he added, cannabis use could be triggering to other residents trying to stay clean and sober.

The Hotel Alder posed other problems. Baggett’s motorized wheelchair made it impossible to close the door of the shared bathroom down the hall from his room, so he had no privacy when using the toilet. He was also unable to bathe himself thoroughly. The bathroom was often unavailable when he needed it, which was frequently because of the water pills he was taking. Several times this put him in the humiliating situation of urinating on himself.

Baggett complained he had trouble sleeping because he couldn’t breathe when he laid down flat. He tried to prop himself up in bed with his two pillows, but it was an inadequate solution.

It became clear over the course of Baggett’s first day out of prison that he was unable to stand without gasping for air and needing oxygen. After he was left alone to get his room in order, I helped him unpack the single garbage bag that contained everything he owned — a couple of old letters, prison paperwork, hygiene items and medical supplies — and made his bed for him. It would be the only time his bed was made while he lived at Hotel Alder.

While the county could house Baggett there for up to six months, he was kicked out after four when he tested positive for THC.