[Read Part I]

Into hell

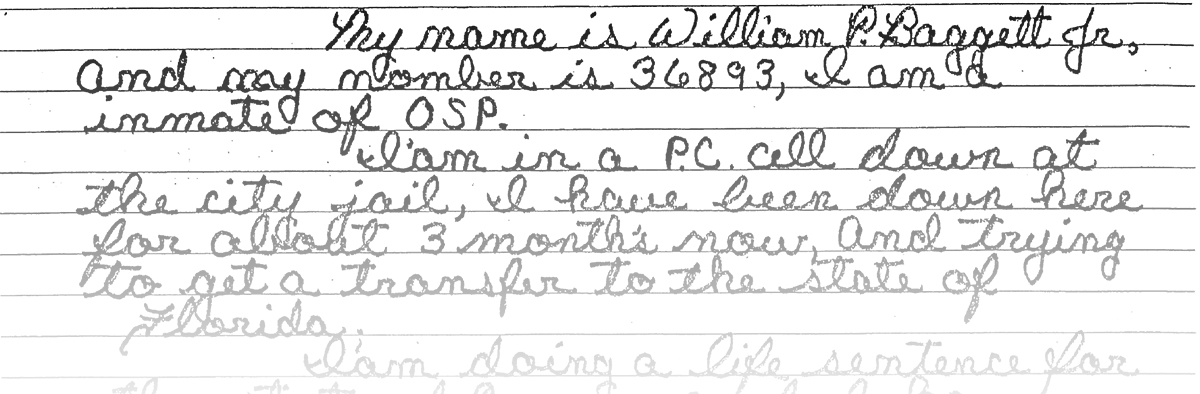

An avid yarn spinner, Billy Baggett often told animated stories about his childhood hijinks and the exploits of his father, whom he glorified. But scratch the surface, and most who knew him would soon see the reality of his upbringing was darker than his well-worn tales let on.

Baggett’s mother, Doris Ann, was just 17 when she gave birth to him in the Deep Southern town of Thomasville, Ga. It was June of 1951, and she named him after his father, the 20-year-old moonshiner she was married to.

The life and death of Billy Baggett

After spending most of his life in prison, Billy Baggett was released into a world he no longer understood, contending with a lifetime of trauma and coming to terms with his imminent death.

Read the full special report.

The young couple soon moved across the state line to Palatka, Fla., where Baggett remembers his father would hide money made from selling his illegal spirits inside the walls of the family’s three-bedroom, 60-foot trailer.

In those days, a gallon of moonshine went for $9.

“It will take your breath away — it’s real strong,” Baggett said. “Daddy used to have this old pickup truck he’d go down to the woods with, and he’d cook off a batch of whiskey, and if it didn’t really taste right, he’d pour it out and put more mash with it and cook it a second time and use it as gas for the truck. It would smoke, but it would run!”

His father, William Baggett Sr., dropped out of school after the ninth grade but found he had a knack for acquiring businesses. He started with a couple of dry cleaners and later added a truck stop and two taverns. Later in life, he’d sell cars.

Baggett fondly remembered piles of gifts under the family Christmas tree each December.

“They say you’re born with silver spoon in your mouth? Not me,” Baggett said on more than one occasion. “I was born with a solid gold spoon in my mouth. They tried to give me everything in the world — and I tried to play Jesse James.”

Baggett said he misbehaved as a kid. He skipped school, drank his father’s booze, stole petty items and sassed authority. Throughout his life, he consistently described his childhood to prison psychologists as one rife with domestic violence.

Earlier this year, from his hospital bed on the third floor of Legacy Good Samaritan Medical Center in Northwest Portland, he relayed a story about the time he watched his mother extinguish a cigarette against the skin of his father’s cheek.

“I thought one day, they were gonna kill each other,” he said.

Before their eventual divorce, his parents brought two more children into the world. Randy Baggett was born when Billy was 5, and their sister, DeAnne Baggett, came along when Billy was 15.

Now DeAnne Harrell, his sister remembers family Christmases differently, with no recollection of extravagant gift giving, though her oldest brother was already institutionalized by the time she was born.

“My daddy was a mean man. He was mean. And he handled a lot of things with violence,” Harrell recalled. “It was alcohol induced. My parents didn’t do drugs, but they were both alcoholics.”

Baggett Sr. was also an active member of the local Ku Klux Klan, she said.

His youngest son, Randy, suffered from a rare but debilitating immune deficiency disorder, hypogammaglobulinemia — similar to the “bubble boy” disease.

“I really honestly think that probably had something to do with Billy’s problems,” Harrell said, “just because here he was, the oldest child, and Randy was the youngest child (before Harrell was born), and Randy got all the attention from my parents.”

Baggett loved his little brother dearly, and as a child, he tried to protect him from the poking and prodding of doctors by acting as a blockade and throwing fits. This made it difficult for his parents to bring him along to the countless hospital visits. Instead, he’d often be sent to live with relatives for extended periods of time.

The family never expected Randy to live past age 7. He lived to age 26, dying while Baggett was in prison.

“My mom and daddy spent so much time with him that I felt rejected,” Baggett said. “I couldn’t handle that rejection, so I done everything I could to get attention, even if it was wrong, even if I knew I was going to get an ass-whoopin’.”

He said his father beat him mercilessly and often, starting at age 6. “I don’t remember one day I didn’t get my ass tore up with a belt,” he said. “But I deserved every one of them.”

As an adult, Baggett advised parents to never hit their children. “Take away a toy instead,” he’d say. It was something he felt strongly about.

Baggett also said a cousin sexually abused him when he was a child. While it was a story Baggett repeated throughout the years to counselors and psychiatrists, it was an allegation his sister said she doesn’t believe.

“It didn’t happen once; it happened a bunch,” he said. “We’ll keep his name out of it. He’s still alive. I don’t want to hurt him. He grew up and grew out of that. I grew up and grew out of it.”

Records show Baggett ran away from home repeatedly in his adolescence. He began drinking at age 6, heavily at age 13. After running away, he was sent to live at a training school at age 14, then at the Youth Development Center in Georgia for stealing cars, or “joyriding,” as he called it, when he was 15. Both were juvenile correctional facilities.

“I didn’t want to go to school,” he said. “After the first grade, mine was nothing but straight F’s. I wouldn’t go. Drop me off at the front door, I was out the back door.”

He said he never played a game of baseball, basketball or football in his life. “I don’t know how,” he said. “All I wanted to do is play Huckleberry Finn and go swimming and fishing and climbing trees and running from the law.”

He didn’t fit in and felt like something was wrong with him. He was placed in special-education classes. He dropped out of school entirely after the seventh grade.

Later in life, he was assessed as having an IQ of 87 during a psychological evaluation in prison. His sister lamented he had “mental problems.”

“You gotta understand that I was borderline retarded,” Baggett said. “With that mentality and not having an education, I grew up in a make-believe world, thinking everything was right, but it wasn’t.”

In 1968, at age 17, he married Martha Jean Norse in his parents’ living room. Martha was five months pregnant when Baggett was sent to prison the next year, now as an adult, for burglary and car theft. First he went to Lee State Prison, then to the Georgia State Prison in Reidsville. He was sentenced to six years but would serve only three.

While he was locked up, Martha divorced him and remarried. He never would establish a relationship with his only child, a daughter, who did not respond to an interview request from Street Roots. She didn’t respond to a request on Baggett’s behalf to reconnect with him before his death either.

Until the day he died, Baggett said her mother, Martha Jean, was the love of his life, although she completely cut off contact with him decades ago.

One year at Christmas, Baggett called his sister’s house from prison, and she put his daughter on the phone with him. It was the only time they’d speak. He remembers it fondly. He told her he loved her, he said. Overhearing the conversation, Harrell said her niece was cold when talking to the father who’d been in prison all her life. “She told him, ‘You do the crime, you do the time,’” Harrell recalled.

It was during his first prison sentence, in Reidsville in 1969, that Baggett ran into a friend from juvenile detention named John Gardner.

“John was like an adopted brother. Every time my mom and daddy come to see me, they would come see Johnnie, too,” Baggett said.

He recalled that one night, two prison guards came into Baggett’s cell to wake him and escort him to the hospital floor. They mistakenly thought Baggett was related to Gardner, and therefore it was policy to inform him of the news: Gardner had been brutally raped and murdered.

“Five grown men took him in the back of the dormitory, wrapped a guitar string around his throat with a knife in his side, and cut his pants off and raped him and choked him to death,” Baggett said. “I was telling people, if I find out who killed my little brother, I’d kill them. But word got to those same five guys, and one night they rode down on me and they treated me the same way they treated John. They put a guitar string around my neck, and they cut my clothes off.” His eyes began to well with tears, as they often did when he recounted violent experiences. “Three of them took me,” he said.

Baggett recounted this sexual assault during numerous psychological evaluations over the years.

The Georgia Department of Corrections could not verify Gardner’s death, but the state archives indicated there was a prisoner by that name in Reidsville in 1968, who was close to Baggett’s age.

“This entire ordeal stuck with me in my head when I got out,” Baggett said.

He drank heavily, and seeing his ex-wife remarried made it worse.

“I didn’t want to be around another man raising my daughter. It hurt me too bad,” he said. “So I run off to Florida.”

In Florida, Baggett said, he quickly got involved in the cocaine trade, helping to unload shipments arriving on boats in the backwoods of Miami from Colombia.

This line of work eventually turned sour. Back up north in Palatka, he and a man named Horace “Leroy” Griffin were running in the same dope ring but didn’t like each other.

Baggett initially said that one day in April 1974, he was sent to an empty house to keep watch, but when he got there, Griffin’s lifeless body was already lying on the floor of the bedroom. It was a set up, he said.

According to his file, however, he described the Florida killing to prison authorities as: “I blowed a man’s head off with a shotgun because he was going in another room to get his gun.”

His file also indicated he confessed to a Multnomah County sheriff later that summer that he shot Griffin with a 12-gauge shotgun.

Baggett later admitted his recollection of events that day were foggy at best. He said he was on LSD and was drunk. According to reports, he fled the scene with the murder weapon in the dead man’s car.

Harrell said Baggett’s defense attorney, now deceased, told her family at the time that her brother was innocent and wouldn’t serve much time in a plea deal for manslaughter.

“Billy told me he didn’t (murder Griffin), then he told me that he did,” said Harrell. “I honestly don’t think he knows if he did it or not.”

She said her parents were told at one point that her brother had the mentality of a 7-year-old and that he was prone to believing anything he was told.

“That was his personality,” said Harrell. “If you told him he did something, he would believe it, and then from that time on, it was like, ‘Oh yeah, I did that.’”

Following Griffin’s death, Baggett skipped town. But first, he called his father for help. Baggett Sr. sent his son up to Oregon, where he had a couple of cousins he could lay low with for a while. Baggett said he took his time hitchhiking to Oregon, stopping in Mexico to party for a while along the way. He eventually ran out of money and arrived in Oregon that fall.

He’d be in Portland for only three weeks before murdering Jerry Gerads.

It happened outside a country-western bar, Club Venus, where the two men had gotten into an altercation earlier that night. Gerads, 31, was celebrating his upcoming birthday with his twin brother and a few friends. Staff at the bar said he was drunk, dropping money all over the place. According to witness statements, at one point, he got into an altercation with Baggett. Gerads was kicked out of the bar but returned around 2 a.m. looking for the money he’d lost. When Baggett stumbled out of the bar, he saw Gerads in the parking lot.

What happened next remains unclear. Baggett said he was blackout drunk, but he knows he murdered the man.

“We went back behind the club, and to this day I don’t remember how or why. It’s never really has made any sense, but I shot him six times. I still don’t know what happened,” he said.

Baggett said police had several versions of events they tried to get him to confess to. The one that stuck was that Gerads was sleeping in his car and Baggett lured him out and then shot him.

“If there is ever anything beyond anything I ever done in my life, I’m sorry for that right there more than anything there is,” Baggett said. “There is no way I can bring him back. If I could, he could be walking beside me right now, being my best friend. But I got to one day, I got to go before God, and God will tell me what happened. I can’t forgive myself — I hope my family can forgive me — but for me to forgive myself, is impossible.”

After shooting Gerads, he attempted to hide the body in a secluded area near the Portland airport under some dirt and weeds, and then he fled, driving straight to Buffalo, N.Y. It didn’t take authorities long to name Baggett as a person of interest, or to apprehend him in Gerads’ car. Multnomah County sheriff’s deputies transported him from New York back to Oregon, and it was on the plane they began to question him about the unsolved killing of Leroy Griffin in Palatka, Fla.

Why, in his old age, Baggett so readily admitted to killing one man but not the other is a mystery.

Baggett was handed a life sentence in Oregon for Gerads’ killing and an additional 15 years in Florida for Griffin’s death. He had been incarcerated for four years at Oregon State Penitentiary when, in 1978, Corrections Sgt. Henry Hal Johnson, the president of the corrections employee union, began to sexually assault him.

According to a report Street Roots obtained from Oregon State Police, Baggett complained to the deputy superintendent at the prison that he had been coerced into performing “the act of fellatio” on Johnson over the course of three months, and he wanted it to stop.

Police set up a listening device inside Johnson’s office so they could catch him. It worked.

“When we entered the room, Sgt. Johnson immediately started fumbling with the front of his pants, keeping his back towards us for several seconds,” stated the lieutenant’s report.

“He approached me, and he tried to force me into participating in homosexual activities. He was a voyeur — he liked to watch,” Baggett recalled. “When I wouldn’t do what he wanted me to do, he started beating the hell out of me, and had another officer beat the hell out of me and lock me up (in solitary) for no reason.”

When prisoners are sent to solitary confinement, they are afforded a disciplinary hearing, but Baggett said Johnson’s tactic was to pull him out of solitary before any such review could take place.

“He would get me out so there ain’t no paperwork, and this went on for some time. And I ended up doing what he wanted me to do. So after a while, he wanted to participate. He wanted to not only watch; he wanted to be involved. He forced me to” — Baggett took a long pause, his voice cracking as he continued — “do oral sex on him, and he forced me to do anal sex on me.”

According to the Oregon State Police report, Johnson was not using physical force, however another prisoner told state police officers that when he refused Johnson, his freedoms were taken away.

According to Johnson’s resignation letter, his departure was voluntary and “of my own free will and under no duress.”

No charges were ever pressed against him. He remained in Silverton and went on to work in the grocery industry before retiring in 2002. He died, leaving behind three children, in 2008.

A news brief that ran in the Statesman Journal following the police investigation into Johnson’s assaults was vague and inaccurate. It identified Johnson by last name and initials only. The paper reported that his resignation followed an isolated incident of sexual activity with one inmate.

Based on the police reports, however, the abuse lasted for months and involved several inmates.

Since the time of Baggett’s assault, Oregon has made it a crime for a corrections officer to engage in sexual activity with a prisoner. The crime, known as “custodial sexual misconduct” is a Class C felony and is punishable with up to five years in prison and a $125,000 fine. Oregon was one of the last states to recognize that prisoners are incapable of truly giving consent.

Baggett wanted the truth about what happened to him to come out. With the majority of his life spent in prison, these events in 1978 were among some of his life’s most pivotal, especially considering the consequences.

Just two weeks after Johnson resigned, Baggett was transferred to the federal penitentiary system — an unusual move for a prisoner in state custody. He contended he was being punished for outing Johnson. The only note about the reason for this move in his file reads: “Mr. Baggett was transferred into federal custody in March 1978 as a result of his having difficulties within the Oregon State Prison System.”

Baggett would spend the next five years of his life in some of the most notorious prisons in America. First stop was the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kan., known for housing some of the nation’s most violent offenders. Word quickly got around that Baggett had been providing a sergeant in Oregon with sexual favors.

“The second day I was there,” Baggett said, “three guys walked in my cell carrying butcher knives. And they said, ‘You’ve got one of two choices: You can become a sissy boy — put on makeup and shaving your legs and turning tricks — or you can die.’

“Well, I’m still alive, so what does that tell you I had to do? For almost six years I had to do that.”

Baggett wasn’t a large man, standing about 5 feet 10 inches. He was young; he had thick, long hair on his head but sparse hair on his body; and he was attractive, as noted in a letter from the Multnomah County judge who sentenced him to life in prison.

“Mr. Baggett is a young man of not unattractive appearance,” he wrote. “He has some homosexual tendencies.”

Baggett was transferred among federal penitentiaries — from Leavenworth, to Atlanta, to Memphis, to Cherry Hill, Ind., to Oklahoma and then finally to Lompoc, Calif.

“Everyplace I went, the reputation followed me, and I had to do what I had to do to survive. So, I got involved in that kind of lifestyle,” Baggett said.

Sometimes, he said, it would begin consensually, but often, “it turned into a nightmare.”

“If you see a 20-, 21-year-old boy, no hair, something’s definitely going to happen. That’s how they make them girls. Some guys go in with a two-year sentence, end up with life because they fight back,” he said.

The Aryan Brotherhood approached him on three occasions to offer him protection, he said. He refused each time, knowing that protection came for a price.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act, or PREA, was signed into law in 2003. It took another nine years before corrections facilities were required to give prisoners ways to report sexual assault. Prison rape, however, is far from eliminated. In 2015, more than 1,400 allegations of rape were determined valid, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Just last month, a transgender woman’s lawsuit against the Georgia Department of Corrections for failing to protect her from repeated sexual assaults was widely reported. Ashley Diamond was housed at the same prison in Reidsville, Ga., where Baggett was first gang-raped as a young man serving his first adult prison sentence in 1969.

Oregon’s Snake River Correctional Institution and Two Rivers Correctional Institution, where Baggett would also spend many years of his sentence later in life, were more violent than Oregon State Penitentiary, he said, but none were as brutal as the nation’s federal prisons.

He said he’d never forget the screaming.

“Seeing four or five inmates go into a youngster’s cell to rape him,” he said, “you wanna help, but if you do, they’ll do the same to you. You close your eyes, close your mind. But how do you shut it out? I hear things. I can hear ghosts.”

Prison “wasn’t all bad,” Baggett said. He described good days, too — days that revolved around escapism through intoxication.

He also had a few memorable long-term relationships with other prisoners, men he loved.

First there was “Jackie,” the bank robber from South Carolina. Jackie was dealing heroin inside federal prison. That’s when Baggett began injecting drugs.

Baggett’s father saw track marks on his arms during a visit once in 1979 and asked the warden to lock him up to get him off heroin. After Baggett detoxed, Jackie would only give him meth, which he mainlined. He would use hard drugs for years within the prison system, though he was rarely disciplined for drug use.

Despite his protests, Baggett was transferred back to Oregon State Penitentiary in 1982. The assistant superintendent there had penned a letter to the Federal Bureau of Prisons stating that Oregon was having budgetary issues and could no longer afford to board Baggett in federal prison.

Once back in Oregon, he began a relationship with another prisoner, but that relationship dissolved when both men were transferred from the penitentiary after acting as informants.

But Baggett’s true gender identity and sexuality eluded him throughout his life. “I don’t want to be gay,” he said as he neared his death. “I’m just totally, totally confused.”

In the telling of his story, Baggett was adamant two events be brought to light. The first was the sexual assault at the hands of Sgt. Johnson. The second was another incident at Oregon State Penitentiary in 1985 that Street Roots was unable to fully substantiate.

Something transpired that put Baggett at odds with other inmates around that time and led to his transfer, once again, out of state. This time he was sent to a state prison in Wyoming.

Baggett claimed he uncovered a plot among other prisoners to start a riot that would serve as cover for killing the assistant superintendent, J. C. Keeney. He said he helped prison staff locate two .38 revolvers that had been smuggled into the prison inside of paint canisters for that purpose.

Oregon Department of Corrections has no record of this incident, nor does Oregon State Police. But state police did have a report for a 1984 in-prison drug possession conviction against the same inmate Baggett said had masterminded the assassination plan. It was a conviction that added time to the man’s sentence.

There were also several notes about an assassination plot in Baggett’s file. In 1998, an interoffice memo a corrections captain penned stated: “Mr. Doran, Baggett’s Counselor, has confirmed with me that in 1985 an incident did occur where Baggett provided information regarding an assassination conspiracy and drug trafficking.”

The same counselor entered into Baggett’s file that he’d spoken to Baggett’s parents, William Baggett Sr. and Doris Ann Rayburn, about their son. They confirmed his allegations. “There definitely seems to be something went on but no documentation of what or how,” he wrote.

An undated memo from Keeney’s boss, Superintendent Hoyt Cupp, in what appears to be 1984 or early 1985, indicated Baggett was in the prison’s segregated housing unit to protect him from prisoners he owed gambling debts to, and it attributed that information to Baggett’s psychologist. But even then, according to the same document, Cupp noted that Baggett insisted he was in protective custody because he had “informed the authorities at the institution of a gun in another inmate’s possession.”

Street Roots was unable to locate the former corrections counselor, Larry Doran, but did track down Keeney, now retired and living in Arizona.

Keeney said he put in a good word for Baggett with the parole board for his help with the investigation into Sgt. Johnson’s sexual abuse in 1978, but the assassination attempt, he said, never happened. And no guns were ever found at the prison on his watch, he said.

He remembers Baggett as a Southerner, small in stature, who was always stirring up trouble. “He was kind of a pest,” said Keeney. “He knew his way around the system pretty well.”

Baggett’s assassination story, in which many lives are saved, as he tells it, may have served him in some ways as atonement for his earlier crimes. Whether true or not, Baggett seemed to believe it, even requesting that Street Roots secretly record him attempting to get Keeney to discuss the incident with him over the phone.

According to Baggett’s prison records, he was transferred to Wyoming Department of Corrections in 1985 “for his protection as an informant.”

Baggett remained in Wyoming state prison for nearly 14 years, where he appeared to settle into a more productive incarceration. He obtained his GED and completed a mechanical drafting class. He enjoyed watching movies in his cell, listening to music on his stereo, playing chess and making leather crafts for his family, according to Wyoming correctional records.

In 1998, he was transferred back to Oregon. This time he was housed at Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution. That’s when the suicide attempts began.

He was paranoid, constantly fearing he would be killed for being a rat. He was on and off suicide watch every few months.

Photos of a bed sheet hanging from a vent 10 feet off the ground in his cell show how he had tried to hang himself in April 1999. He told prison staff he couldn’t handle his life any longer.

One year and eight days later, he would attempt suicide again while in solitary confinement at Snake River. He was in solitary confinement frequently and sometimes for long periods of time in those days, often for using foul language and disrespecting prison guards. A few times he went for failed drug tests, property damage, sex acts and for disobeying orders. In 1999, he spent a period of three months in solitary confinement and was issued a $200 fine after repeated unwanted sexual advances toward a cellmate.

The repeated isolation over the years took its toll. At times he thought he was losing his mind.

The first Christmas after his father died in 2003, Baggett was once again in solitary confinement, alone with his memories of childhood holidays made merry by his father’s over-the-top toy shopping.

Despite a tumultuous relationship with his parents in his youth, they remained the only constant source of support throughout Baggett’s life.

They traveled from Georgia to visit him regularly in prisons across the country. Three years before he died, Baggett Sr. paid Oregon Department of Corrections more than $5,000 to have his son transferred to Florida, where he would visit him more frequently in his old age.

Two years after his father’s death, Baggett was diagnosed with HIV.

“At first I wanted to kill myself; I couldn’t handle it. But after two or three months went by, I started thinking, it ain’t death I want; I want to live,” he said.

He found Jesus and began attending church services, though he said the lifestyle of prostitution that had defined much of his time behind bars still haunted him. Other prisoners dismissed his diagnosis and pressured him into sexual acts, he said. An indication they likely had the virus, too, he said.

He was baptized in March 2006. His mother died two months later. Six years later, he finished his sentence in Florida but was required to report for parole in Portland — a city he had only vague memories of from the three weeks he spent there leading up to the murder he committed in 1974.