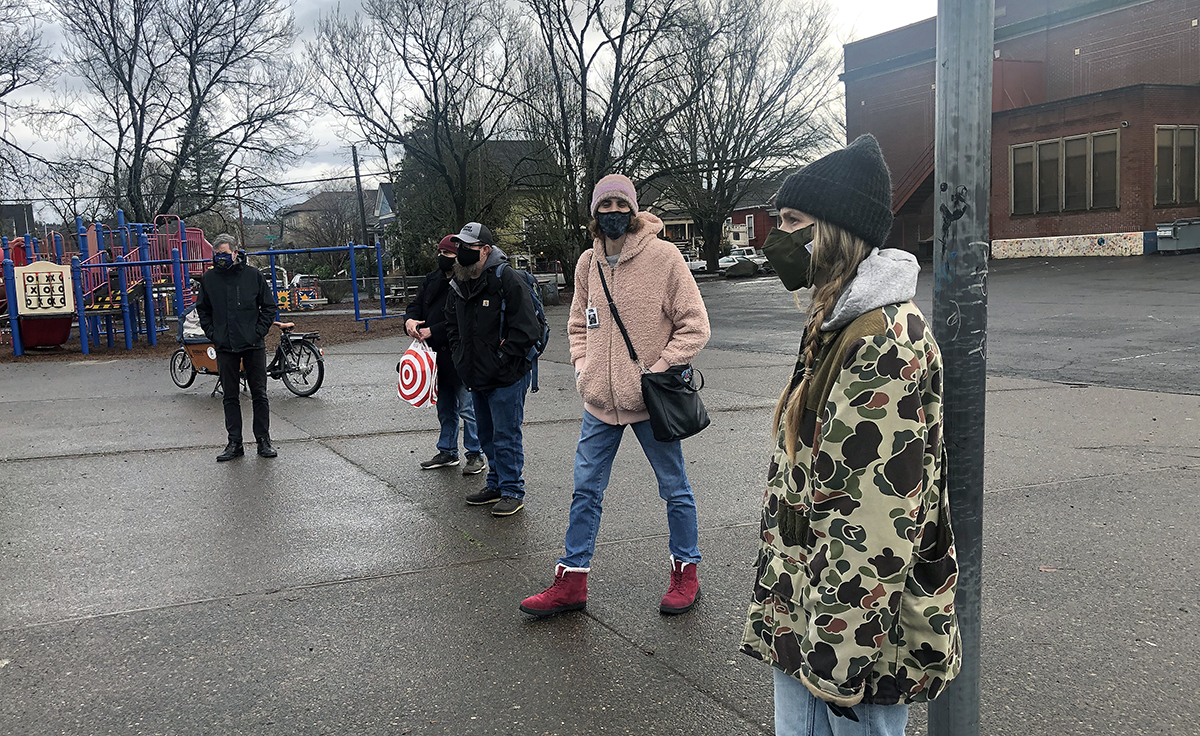

The circle was big. Standing 6 feet apart, neighbors — at first mostly people who are housed, and slowly, more and more unhoused — faced each other in the grassy park at Sunnyside Environmental School in Southeast Portland. As each person walked up to the circle, people stepped back, widening the circle under a clear sky on the day after Christmas. Tents rimmed the park just outside the fence.

There was always room for more.

This circle was suggested by Street Roots Ambassador Program manager Raven Drake after Street Roots board member Jay Parasco invited her to a Sunnyside neighborhood meeting. Emotions were running high among neighbors who saw tents move into their inner Southeast Portland neighborhoods. Some people were suggesting a sanctioned camp village. Some neighbors expressed stress.

Raven listened.

Then she suggested a first step was to come to know more people who were camping. Listen through relationships. She offered to bring Street Roots ambassadors Matt Perkins and Brian Bartel, who could help people engage in conversations across housing status.

This is a story in progress — as all human stories are — and there’s an earlier chapter to this one.

Just before Thanksgiving, the city displaced campers at Laurelhurst Park — what’s commonly described as a camp sweep — illustrating a fact that’s clear after every eviction:

People have to live somewhere.

When they are evicted from their living space, they don’t just disappear. They go somewhere with new traumas.

STREET ROOTS NEWS: After painful sweep of Laurelhurst Park, unhoused residents want a space to exist

The next chapter of the Laurelhurst camp sweeps began blocks away in Sunnyside Park, where many campers relocated. Of course, there are chapters written elsewhere. Some people went to Mt. Scott Community Shelter; some dipped further into hiding. I always think of a man who told me that to avoid displacements, he sometimes sleeps in a tree.

While the Joint Office of Homeless Services coordinates the city of Portland with Multnomah County to connect housing, shelters and services to people in need, the city has a separate program that mostly contracts out these camp sweeps to Rapid Response BioHazard, and the mayor oversees this. The program has a mouthful of a name that would make George Orwell shudder — the Homelessness and Urban Camping Impact Reduction Program, usually shortened to HUCIRP, housed under the Office of Management and Finance.

HUCIRP accumulates its data from reports. It is, to be candid, neighbors reporting on neighbors, a kind of everyday surveillance that has constant repercussions. A complaint-driven system means the city expends energy on thousands of decisions that bend toward destruction.

But it’s important to note that HUCIRP can take on constructive measures, too. This is an office that sites toilets and can offer garbage resources. The impact can be one that’s supportive for unhoused people, and it’s incumbent on all of us to call for that, rather than instigate sweeps, as well as consider the everyday actions we can take in relation to our unhoused neighbors.

DIRECTOR'S DESK: Access to hygiene is a human right, and Portland is stepping up

Perhaps the Sunnyside neighborhood can be a leader in taking actions built from relationships and listening.

Part of what that circle became that day after Christmas was a way to hold space.

Many neighbors came, including John Mayer of Beacon PDX and state Rep. Rob Nosse. One unhoused neighbor walked from her tent to the circle, describing how her biggest need was laundry. Clothes, wet and dirty in the Portland weather, decay into garbage. She suggested a barter system. Perhaps the unhoused neighbors could offer a service such as picking up garbage, she suggested, if housed neighbors could help them get laundry to the neighborhood laundromats? Neighbors began to plan.

As people held space, they learned more. There was, it turned out, a neighbor who already was delivering sandwiches. There was a man in a house across the street who came by and suggested he could bring pallets for all the tents to lift them off the ground. One unhoused neighbor joined the circle on his bike, and explained that campers needed security in numbers — enough people so that, for example, he could leave to try to get a shower without losing his possessions.

It was clear that there were new opportunities arising from these conversations.

Economic segregation means that poverty, although widespread, is not apparent in every neighborhood. It’s harder to be in relation. When camps move into these neighborhoods, these hard truths are clearer.

A Multnomah County report last year showed that more than a third of all residents can’t meet basic needs based on income. If the circle had 100 residents, 34 people would not make enough income to meet their basic needs — and that was pre-COVID-19 data. People need more money, and the things they need to purchase — like housing — must be less expensive.

But the truth is, scenes of homelessness simply make visible the deep injuries of our society and economic system. Homelessness is not separate from the fact billionaires collectively increased their wealth by a trillion dollars during the pandemic. It is not separate that descendants of people who were enslaved or pushed off their land are now locked up by the same system, released to poverty. It’s just not separate that a family who was denied housing wealth earlier in the century is evicted from their housing now, perhaps doubling up with other family members in insufficient housing. Or that others were pushed into homelessness from mortgages designed to fail.

Camps are simply a visible aspect of systemic injustices. Somehow we need to take in the duality: While we grapple with the larger systems that drive severe deprivation, we need to love those who are strangers enough that they are kin, stepping back to build an ever-widening circle.