Although contemporary Indigenous communities are vibrant and diverse, many think of Native Americans in the past tense.

A local Indigenous curator reminds viewers of the enduring presence of Indigenous communities in a new exhibit featuring 14 regional Native artists.

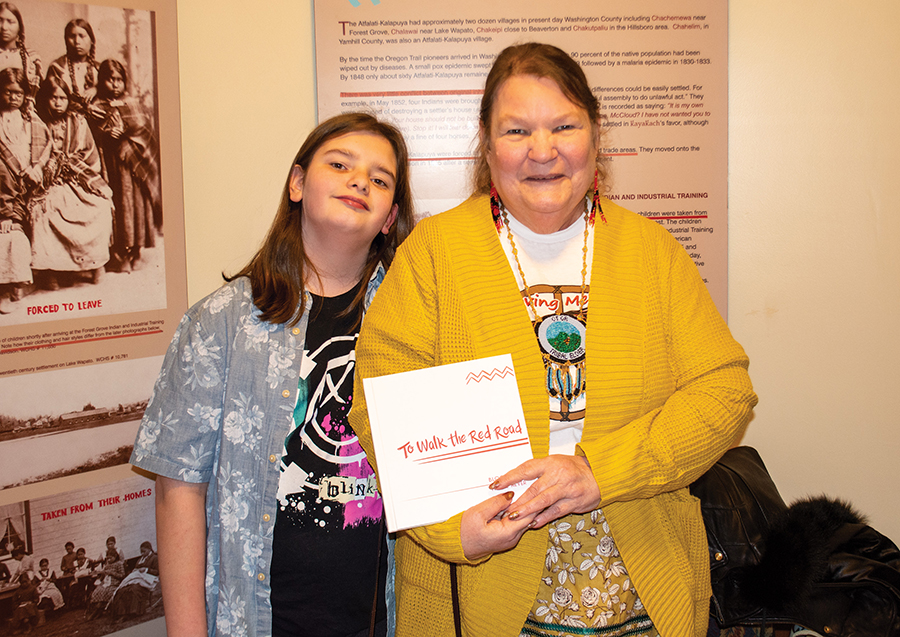

Steph Littlebird, an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, is a multi-talented creative whose exhibit, “This IS Kalapuyan Land,” opened in February at Portland’s Pittock Mansion. Littlebird is both the curator and a contributing artist to the exhibit.

Littlebird, also a painter, graphic designer, illustrator and writer, pushes back against anti-Indigenous racism in her work. Defying stereotypes of Native people, Littlebird's work reminds viewers of contemporary Indigenous communities' rich and continuing presence.

“This IS Kalapuyan Land” is half art, half history. Littlebird debuted the exhibition in 2019 at the Five Oaks Museum in Portland. The exhibit garnered national recognition, appearing on PBS Newshour before being forced to close early in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Five Oaks Museum had a pre-existing display of informational panels detailing Oregon’s history, which Littlebird noticed was rife with inaccuracies. Littlebird collaborated with David G. Lewis, a Grand Ronde historian and preeminent scholar on the history of Oregon’s tribes, to correct inaccurate information about tribes on the panels. The exhibit, now at Pittock Mansion, features modified panels paired with contemporary art by a group of regional Indigenous artists.

The other half of the exhibit is an array of Indigenous art in various forms, from paintings to textiles.

Growing recognition of Littlebird’s talent is leading them to projects with a national presence.

A self-titled “nerd,” Littlebird recently landed a “dream” opportunity after Lucas Films tapped her to illustrate the cover of “Star Wars: Into The Void,” which will re-release in May.

As Street Roots reported in March, Littlebird also recently debuted her first picture book, “My Powerful Hair,” written by Carole Lindstrom, which celebrates the cultural importance of hair in Native communities.

Street Roots sat down with Littlebird to discuss her work.

This interview is edited for length and clarity.

Melanie Henshaw: How does it feel to have your exhibit open at Pittock Mansion?

Steph Littlebird: I'm excited. There's been lots of positive feedback already.

It's just an opportunity for folks who became familiar with the exhibition after it originally closed early due to the pandemic to go and see it in person. Because what's weird about this exhibition is that it actually got more popular after it closed, so it's become this sort of local cultural phenomenon.

I'm just excited for there to be this opportunity that's actually pretty lengthy, from February through July, to be able to get people up there to see it.

Henshaw: How does this iteration of “This IS Kalapuyan Land” differ from the original exhibit?

Littlebird: When we originally created the exhibition, we wanted the artworks that were included to represent the contemporary Indigenous community in Oregon, and that meant not just having Kalapuyan artists but actually having all kinds of Native artists in the region because that's the reality of our community now, is that it is very diverse.

Oregon is one of the largest urban Indian populations in the country. Portland, in particular, has 50,000 Natives or something. I think it's within the top 10 places in the country for Natives.

So it's a very diverse community, and that's kind of how I made the decision for this iteration was to say, ‘We're going to keep going with that as our intention of representing the sort of diversity of our community here in Oregon,’ and that means that there are Kalapuyans, there's Chinook people, there are people from Umatilla and Warm Springs, and representing all of these communities within Oregon that are connected.

For me, it's just exciting to be able to share these contemporary artists with people because a lot of people see Native people as being in the past or (think) that we don't exist now.

So by incorporating this art made by people living in the local community now, people can see the diversity and see how very much alive the community is. Particularly because the art is only half of the exhibition; the other half is history.

We don't want people to be just thinking about the past but also thinking about how our community has evolved since all of those things have occurred. So it really pairs well with the history and makes people think more about the people living in their community now. Indigenous people are your neighbors, and your friends and artists, all kinds of things, but people don't necessarily realize that. So the art functions in that way of reminding people that we are still here.

Henshaw: How did it feel to work on a project that was already “completed”?

Littlebird: It's kind of surreal to be coming into something that was already made – not the artwork, but the historical exhibition – it was a pre-existing exhibition that the museum made with funding from the Grand Ronde tribe, but the museum actually didn't consult them.

So there were a lot of inaccuracies and errors in the exhibition, and the museum did not take feedback from the tribes about it. Because the exhibition was actually made 15 years prior to my getting to it, it was like this opportunity not only for me to correct errors but also to right the wrongs of this museum and how it interacted with the local Indigenous community in previous times.

Luckily, the museum is being run by different people who are much more community-oriented and open to critique and healing those things. So it was cool; I got to be an authority. Working with a tribal scholar also helped. His name is David Lewis, and he has a doctorate and is our tribal historian. I was working with him to right the wrongs that are written about us throughout the exhibition and also to honor him because he actually did provide the museum with feedback back when they had originally made it, and they did not incorporate it.

So it was a way for me to go back to how they had wronged our tribal historian nearly two decades before and right that, and bring him back in so that those corrections could be made.

For me, it was like righting a bunch of wrongs, correcting errors, both in the panels themselves but also in the way that the institution had dealt with Indigenous communities beforehand.

For me, it felt very powerful, especially because — as evidenced by the way that this museum treated us in the creation of these panels — is that museums, historians (and) anthropologists don't see Native people as the authority on their own histories.

So when we talk about how we have been in the region since before the Missoula floods, we've been told for decades that's a lie, and we didn't know what we were talking about. And recently, scientists caught up and said, ‘Oh, wait, no, they have been here at least that long.’

So we've been gaslit by these institutions, so in a way, for me, it's healing, not just for myself, but for my ancestors who were told they didn't know their own histories. It's a way to rectify those things — so, really powerful, but also a lot of responsibility to get it right.

I mean, our community isn't afraid of calling you out if you fuck something up. Like, I'm fully aware that if I don't honor this project in the right way, I could do harm to my community, all kinds of things, right?

So, it’s very much important for me to get it right and to take the errors that were committed previously and rectify them somehow. Maybe it's never perfect, but trying is important. These institutions also need to learn how to recognize when they've made errors.

Henshaw: How would you describe your style?

Littlebird: Man, it's kind of all over the place. It really depends on where I am.

I actually went to school for painting, and so I'm much more passionate about painting than I am about illustration, but because illustration has sort of become what people have known me for, I’ve just been fully in the illustration world the last year and have barely painted anything.

So I've grown to love it and recognize it's huge for me as a political activist, and so I use it in different ways. But a lot of the work that I make, no matter if it's painted or digital, usually relates to my Indigenous identity. But also, a lot of the work that I share on Instagram is going to be stuff that I want people to learn.

Right now, I've been doing a lot of stuff related to fast food, redoing the Land O'Lakes logo and redoing the McDonald's logo, playing with symbols and making comments about colonialism through graphic work, as I'm a designer as well. I do logo work and things.

It’s a way for me to combine all of these interests that I have. Right now, the digital stuff is really where I get to play with my political voice in a way, to be an activist through my image-making. I'm having a lot of fun with it right now, which is good.

In illustration, it's a lot of work staring at a computer or a tablet screen for hours and hours, but it's fun to make stuff that's inspiring to other people, or that resonates with them, especially right now with like the economy and everything.

I feel like people are restless and unhappy with the way the world is. So I'm using my personal artwork to sort of talk about that restlessness that I see in the millennial generation and also the Gen Z generation. I just see restlessness happening right now, and it's a way for me to contribute to that conversation.

Painting is the place where I really learned how to be an artist and also where I learned to use art as a healing tool. I really believe, first and foremost, art can heal, and that art healed me.

It continues to heal me and has helped me work through so many hard times in my life. So, for me, painting is like meditation, it's all of those things, and it's just a way for me to create a safe space for myself when sometimes the world is not that safe for me or my community.

Littlebird’s work is available on her Instagram (@artnerdforever) and for sale in her Etsy shop. “This IS Kalapuyan Land” is on exhibit at Pittock Mansion through July 23. “Star Wars: Into the Void” debuts in May.

Street Roots is an award-winning weekly investigative publication covering economic, environmental and social inequity. The newspaper is sold in Portland, Oregon, by people experiencing homelessness and/or extreme poverty as means of earning an income with dignity. Street Roots newspaper operates independently of Street Roots advocacy and is a part of the Street Roots organization. Learn more about Street Roots. Support your community newspaper by making a one-time or recurring gift today.

© 2023 Street Roots. All rights reserved. | To request permission to reuse content, email editor@streetroots.org or call 503-228-5657, ext. 404