In March 2020, at least 676 Oregon households faced the prospect of losing their homes. Each received an eviction notice that month.

COVID-19 had already killed at least 18 people in Oregon and hospitalized another 690. Workplaces were shutting down, and then-Gov. Kate Brown issued the state’s first pandemic stay-at-home order.

Things were falling apart — but there was still rent to be paid.

Eviction moratoriums kept most people in their homes but didn’t protect them from accumulating back rent. A year later, as eviction moratoriums were set to expire, tens of thousands of Oregonians faced back rent they couldn’t afford to pay. An eviction crisis of unprecedented proportions loomed on the horizon.

In response, federal and state funds were piped to landlords and renters. Alongside these efforts, state legislators deployed $150 million to the Landlord Compensation Fund, or LCF, a core program meant to stabilize housing and “provide relief to residential landlords who have been unable to collect tenant rent due to tenant hardships.” Passed in December 2020, now-Gov. Tina Kotek was the bill's chief sponsor. Then-state Rep. Kotek deemed the funds “necessary to protect the public health, safety and welfare.”

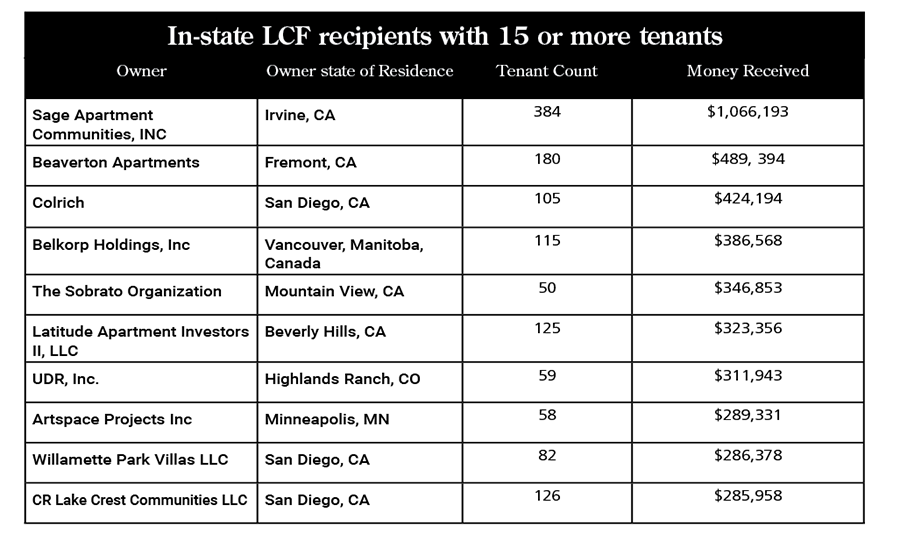

A Street Roots investigation found among landlords with 15 or more tenants who successfully applied for Landlord Compensation Fund money, at least 32% — 92 landlords receiving approximately $13.5 million — were property owners based outside Oregon.

The terms? The state would provide landlords 80% of the unpaid rent they were owed by qualifying tenants from April 1, 2020, to the time of applying. In turn, the state would require landlords to forgive the remaining 20% of unpaid rent.

While preventing an outright eviction crisis at the height of the pandemic was essential, LCF data sheds light on the composition of the real estate industry, which is increasingly consolidated, frequently by out-of-state players with investments nationwide. During this push to stop evictions, the state didn’t enact a system consistently tracking which specific entity received funds — so in many instances, it isn’t clear who received funds or if the funds went out of state.

Data battles

Street Roots faced several challenges in accessing data, originally requesting LCF recipient records in March 2022. Oregon Housing and Community Services, or OHCS, which administered the program, denied the request citing privacy concerns.

After several months of negotiations between Street Roots and OHCS, OHCS agreed to provide records, but only for landlords with 15 or more tenants, again citing privacy concerns. OHCS eventually handed over a batch of data in October 2022.

At that time, Street Roots received a list of what it believed to be 467 LCF recipients that received $57.6 million in funds, per its request. While conducting data analysis, Street Roots found a large number of recipients were property management companies, prompting questions about who received funds the state dispersed to property management companies, since those companies often manage rentals for other owners.

Street Roots later learned OHCS provided data including both landlords and property managers with no distinction between the two.

In a statement to Street Roots, Delia Hernandez, a spokesperson for OHCS, said the legislation — House Bill 4401 — didn’t require a distinction between landlords and property managers, thus the OHCS system didn’t track it.

“The legislation under HB 4401 broadly defined the term ‘landlord’ permitting property manager and owner to be treated interchangeably,” Hernandez told Street Roots in an email. “Per this legislation, qualification for this program did not include owner- or landlord-based requirements. Tax information with ownership was collected as part of program compliance. The program focused on eliminating tenant debt first and foremost, and the entity that controls and has authority over that debt can vary depending on the ownership and management relationship at a property.”

Street Roots reiterated its request for LCF recipient data specifically for property owners and received a list of 284 recipients — almost half the original number of recipients, with a corresponding drop in funds.

However, while analyzing the second data set, Street Roots found discrepancies in tenant counts and funding amounts for property owners included in both data sets — funding amounts in the second data set were only a fraction of the funding amounts in the first data set.

When provided with the discrepancies, an OHCS spokesperson said an error in the data collection process was to blame before supplying yet a third batch of data.

Street Roots used the third data set in this story. However, the state is unable to provide a complete list of recipients with 15 or more tenants — an accounting of which person or company actually received the money — but only a list of successful applicants, some of which are property managers applying on behalf of a property owner.

OHCS’ inability to provide accurate data distinguishing between applicants that received money on their own behalf and applicants that received money on behalf of an owner stems from an initial system that failed to track the ownership status of recipients.

Instead, the system only tracked the applicant, meaning that when property managers secured LCF funds on behalf of landlords, those properties weren’t consistently separated according to ownership — they were aggregated under the property managers, whose management portfolios often include multiple landlords and/or manager-owned properties.

According to OHCS, after the initial push to process applications, OHCS shared grant agreements with local public housing authorities, which then verified ownership or management of the property by the landlord and dispersed the funds.

Because different portions of the application process were handled by different agencies — state and local — OHCS does not have a cohesive set of data separating the two.

In practice, this system means complete data accounting for property management companies wasn't available.

Ultimately, OHCS provided Street Roots with a list of payee addresses and removed property management companies. The resulting list accounts for more than 280 recipients. The remaining records include recipients where the owner of a property was clearly identifiable. While not a comprehensive list, the records are a helpful data sample demonstrating out-of-state ownership and consolidation.

Who received funds?

The bulk of funds distributed through the LCF went to smaller property owners and managers. According to Hernandez, 4,538 landlords with fewer than 15 tenants applied for funding. In total, the LCF dispersed $93.2 million to these recipients to stay evictions.

OHCS did not release funding records for these recipients, citing tenant privacy concerns, it is unclear how many were out of state.

According to OHCS data, of 284 landlords with 15 or more tenants, 92 are based out of state — more than a third. The remaining 194 were based in Oregon.

The state dispensed just over $38 million to these 284 landlords to stop evictions. Of this, $24.5 million went to Oregon-based owners and more than $13.5 million went out of state. These numbers do not account for funds disbursed to out-of-state landlords via property managers.

The majority of out-of-state landlords — 65 — were based in California. Washington state followed with 13 landlords receiving funds. In total, over $10 million went to California-based landlords.

The top recipient of LCF funds was the Irvine, California-based Sage Apartment Communities, Inc., which received over $1.06 million.

At least 19 out-of-state landlords received more than $200,000.

Top 10 out-of-state recipients:

1. Sage Apartment Communities — $1,066,193

Sage Apartment Communities is an investment property group based in Irvine, California, seeking to expand affordable housing in key markets in the United States, according to an article in Globest. According to OpenCorporates, the real estate conglomerate has branches in at least 10 states, including New Jersey, Nevada, California, Texas, Pennsylvania and Hawaii.

2. Beaverton Apartments — $489,394

Secretary of State filings show this Beaverton-located apartment complex is owned by the California-based Radecki Business, LLC, which lists branches in Washington, Oregon and California.

3. Colrich — $424,194

Colrich is a California-based real estate, construction and investment firm. Its parent company, Colrich California Construction, INC, has branches in Oregon, Washington and California.

4. Belkorp Holdings, Inc — $386,568

Headquartered in Canada, Belkorp Holdings is a private equity firm investing in property, capital markets and business operations. It has branches in Delaware, Oregon, Texas and Arizona.

5. The Sobrato Organization — $346,853

The Sobrato Organization is a California-based real estate company that boasts a partnership with Apple for the construction of its Cupertino, California headquarters. In 2019, the company surpassed $10 billion in assets.

6. Latitude Apartment Investors II, LLC — $323,356

Latitude Apartment Investors is a national commercial real estate lender headquartered in Delaware, with branches in California, South Carolina and Colorado. According to OpenCorporates, the company is affiliated with Latitude Management Real Estate Holdings, a private real estate fund manager advertising a track record of closing “$4 billion in equity and debt investments over the past 20 years.”

7. UDR, Inc. — $311,943

The LCF piped more than $300,000 to UDR, Inc.’s California branch. The company is headquartered in Maryland and also has branches in New York, New Hampshire and Washington. According to OpenCorporates, UDR’s parent company is United Dominion Realty, which lists at least five subsidiaries of its own.

8. Artspace Projects, Inc. — $289,331

Artspace Projects is a nonprofit that owns and operates spaces for artists and “creative businesses” that include live/work spaces and studies, commercials spaces and other related spaces. The organization has dozens of properties nationwide and in 2020 reported $22.8 million in net assets. Based in Minneapolis, the organization brands itself as “America's leading nonprofit real estate developer of live/work artist housing, artist studios, arts centers, and arts-friendly businesses.”

9. Willamette Park Villas LLC — $286,378

Willamette Park Villas LLC is based in San Diego, California.

10. CR Lake Crest Communities LLC — $285,958

CR Lake Crest Communities LLC is headquartered in Delaware with at least one other branch based in Oregon, according to OpenCorporates. The business operates an “Affordable Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Community” in Milwaukie.

Industry consolidation

The consolidation evident in Oregon’s real estate industry is part of a national trend.

A Pew Trust report found investors bought 24% of all single-family houses sold nationwide in 2021. Since 2021, the rate of investor property purchases has remained at approximately 15-16%.

In Portland, investors purchased 12.6% of homes sold in 2021, an increase of 46.3% from 2020, according to data from Redfin.

As Street Roots reported in April 2022, investor purchases accounted for 41% to 67% of all home purchases in Clark County, Washington, depending on ZIP code.

Most out-of-state companies that received LCF funds own housing in multiple states.

Lawmakers deployed LCF funds to protect renters, and didn’t factor who would receive the funds into their decision-making process. Still, the data exposes the increasing consolidation of real estate ownership and the unintended impacts, such as transferring a large amount of Oregon money out of state. Companies with properties in multiple states likely received hundreds of thousands in funding from renter protection programs in various states, making them far more likely to weather the pandemic with profits intact.

The profitability of the housing industry has ultimately hurt renters, said Kim McCarty, executive director of the Community Alliance of Tenants.

“The fact that our housing market has changed so that rental housing has become an investment vehicle,” McCarty said. “And because of that, accelerating the rate of exchanging properties, and accelerating the desire for there to be a profit each time.”

The push for profit is driving up prices and making housing increasingly unaffordable, McCarty said.

“It would help to recognize that housing stability is a very, very important value that we should all take seriously because we want our communities to be stable,” McCarty said.

The pandemic wasn’t as bad for landlords as they feared

While there were initial fears from landlords about losing assets from missing rent, federal and state funds prevented much of this potential loss.

Peter Hepburn, a researcher at Princeton’s Eviction Lab, said that research shows the effects of the pandemic on landlords weren’t as severe as they were feared to be.

“So there have been a number of studies that have looked at rent collection statistics and showing relatively minor declines in rent collection during the pandemic,” Hepburn said. “For the most part, rent was paid up at the same levels as before the pandemic.”

A national study by JP Morgan Chase shows that landlords profited overall during 2020. According to the study, some landlords lost rental revenues, particularly early in the pandemic, but many cut expenses, yielding higher balances.

“Since expenses fell more than rental revenues, and rental revenues recovered more than expenses did in June (2020), overall balances were higher during the pandemic,” the study found.

By June 2020, the income balances for landlords studied were between 25-30% higher than the year before. The study notes the balances alone don’t necessarily indicate long-term financial health because the deferred expenses would still need to be addressed in the long term.

Still, federal and state governments deployed funds at unprecedented levels to suspend evictions.

“A great deal of money went out the door very quickly in 2021,” Hepburn said.

According to Hepburn, specific data on how and who benefitted from these funds isn’t available yet, but various data indicate the real estate and rental industries have weathered the pandemic intact. Alongside programs to protect renters, Hepburn said, “there have been a number of expansions of mortgage foreclosure or mortgage forbearance programs,” helping to stabilize property owners.

“There also hasn't been any meaningful uptick in foreclosures,” Hepburn said. “In fact, foreclosures are at record low levels.”

Meanwhile, rent has skyrocketed. In the late-stage pandemic, rising rents have thrust renters into a more expensive market than ever, said McCarty.

“We're seeing the cost of housing going up like every few months, at an accelerated rate,” McCarty said.

Evictions are happening at an unprecedented rate, McCarty said, a trend contributing to the homelessness crisis.

“The rate of eviction is really high,” McCarty said. “People think that for someone who's evicted, that they're just going to go find another place and it doesn't lead to homelessness. And the data is there to make a direct correlation between eviction and homelessness.”

The core result is that housing is less stable, McCarty said, but at the same time, landlords came through the other side of the pandemic with profits intact.

“On the whole, you know, if you look nationwide, landlords did very, very well, financially,” McCarty said. “I don't see indicators that the rental market was profoundly damaged by the public health emergency.

“What I see is that for the most part, most landlords were made whole. And in a way that was unlike any other industry, you know, where somebody is offering an essential service.”

Street Roots is an award-winning weekly investigative publication covering economic, environmental and social inequity. The newspaper is sold in Portland, Oregon, by people experiencing homelessness and/or extreme poverty as means of earning an income with dignity. Street Roots newspaper operates independently of Street Roots advocacy and is a part of the Street Roots organization. Learn more about Street Roots. Support your community newspaper by making a one-time or recurring gift today.

© 2023 Street Roots. All rights reserved. | To request permission to reuse content, email editor@streetroots.org or call 503-228-5657, ext. 404