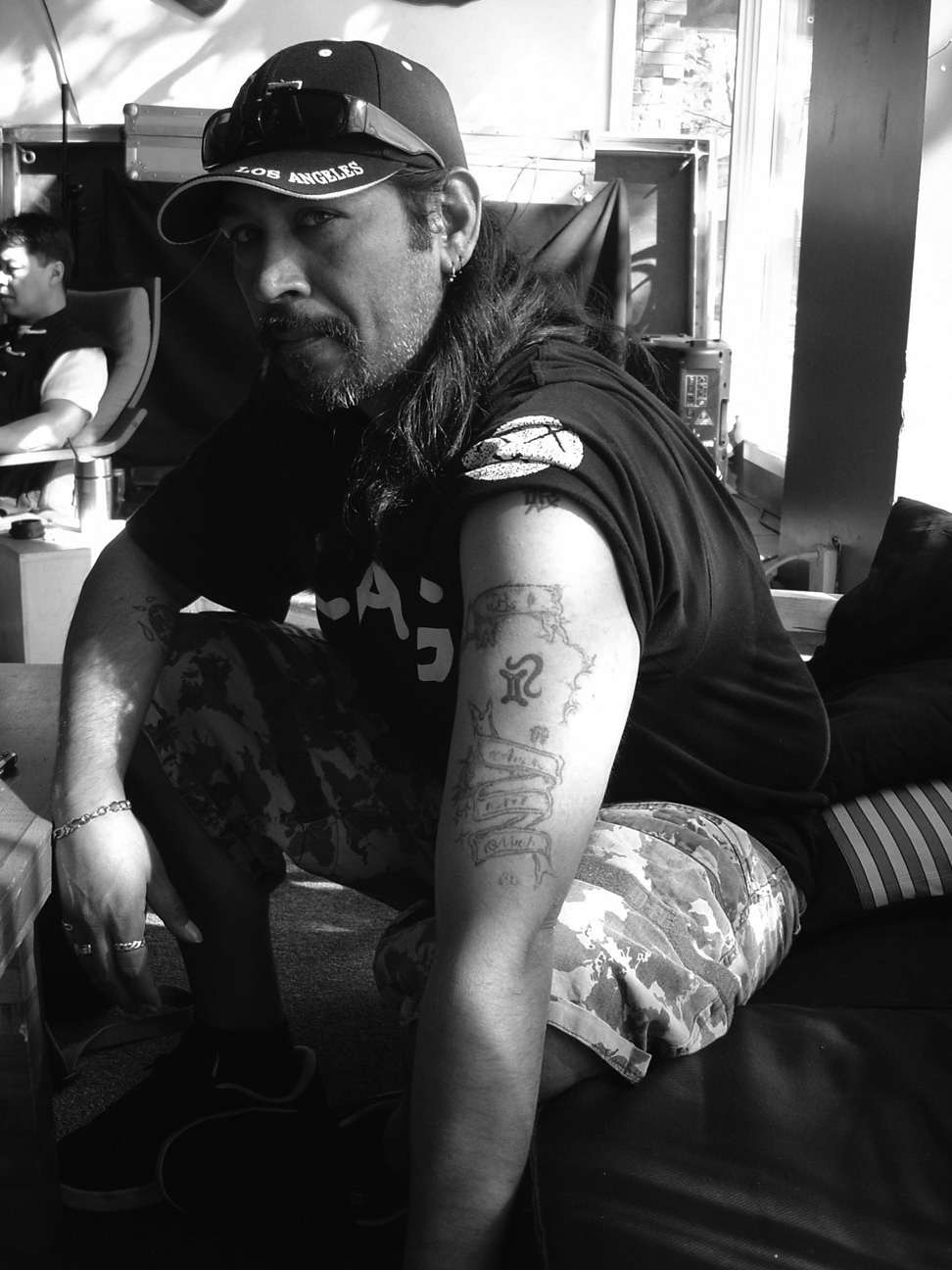

(Art Rios, a member of the Civic Action Group at Sisters Of The Road Cafe, discusses his experiences in and out of prison.)

Matt Gollyhorn remembers it well: sitting uncomfortably on a bench and waiting for the bus — a ride that he had anticipated for almost eight years. The sun reflects off his shiny head, and he stares blankly in front of him. A half empty box of knickknacks sags beside the folds of his undersized sweat suit, and he kicks at gravel with shoes that are two sizes too big. “What am I gonna do now?” He asks aloud, fingering the $220 check in his pocket.

It was all he had to his name after seven and a half years in prison.

According to Jeff Duncan, a research analyst for The Department of Corrections, 52 percent of released offenders in Oregon had no home to go to in 2008. In 2009 alone, says Duncan, 4,461 inmates are scheduled for release. For these individuals, the transition from incarceration into society is difficult, especially for those without family support.

“I had a premonition”

On a spring night in 1999, while he and his older brother waited outside a Portland McDonald’s, Gollyhorn, then 18, had a premonition: he knew that if they went through with their plan they would get caught.

Instead of trusting his instincts, they went ahead and attempted to rob the McDonald’s. They also got caught. Gollyhorn was charged under Oregon’s Measure 11 with three counts of armed robbery, criminal conspiracy and second-degree kidnapping.

Raised in “Felony Flats,” the SE 82nd and Duke area, he recalled growing up around white supremacy and biker bars, and knowing only one black family in the area. He was surrounded by addiction, as well, with both of his parents hooked on narcotics. After being picked on as a young child, Gollyhorn started fighting back. He continued fighting and, consequently, was kicked out of five Portland high schools.

A fellow inmate took him aside when he was first incarcerated and talked to him about figuring out his life. “If it hadn’t been for the one and a half minutes he took out of his time,” says Gollyhorn, “I might not have changed.” Who he was back then, he says, and who he is now are completely different people.

He lost the need to fight, as well as the hatred that he says took so much energy out of him.

Gollyhorn was also able to use his time as best he could. He spent a fair amount of his sentence on a wildland firework crew, where he relearned how to trust, how to appreciate a full day’s work, and how to interact with the outside world.

Nonetheless, re-entering society, he says, was like stepping into a foreign country.

“I’d never paid a bill in my life,” he says. Nor had he used a cell phone or the Internet prior to entering prison. If not for his friends at Sisters of the Road and an ex-con acquaintance who showed him the ropes of Portland’s social services, Gollyhorn might easily have slipped back into a violent lifestyle.

Living For Destiny

The bustling noise of the busy café crowd carries on around Destiny, but the 3-month-old wrapped in a blanket remains oblivious to it, comfortably sleeping in her stroller. The clattering sounds emanating from the counter only 20 feet away do nothing to disturb her, nor does the emotionally charged tale of her mother, Alicia McGinnis, 25, who sits by her.

Destiny has no idea what her mother has gone through the previous 7 years, a time during which McGinnis was incarcerated for 3 1/2 years in Washington for robbery, and then again for 13 months in Oregon’s Coffee Creek Corrections Facility in Wilsonville for first-degree burglary.

Destiny has been well fed and has a roof over her head, something McGinnis is able to provide through Section 8 housing and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families income she receives. These are better days for McGinnis, much different than the many years she spent homeless on and off throughout her life. According to McGinnis, many nights as a child were spent sleeping under the steering wheel in the cab of a truck, her parents, brother and family dog all crammed in beside her.

On another spring night in 1999, McGinnis awoke in a friend’s car to discover that two of her buddies had followed a man from a gas station and had robbed him. According to McGinnis, because she had woken up at the time, it was determined by the police that she was aware of what was transpiring. She was charged as an accessory to robbery and given 3 1/2 years.

“I had just lost custody of my son a couple days before this,” says McGinnis, recalling a situation that she blames in part on her mother, whom she described as a drug addict who regularly caused problems for her and her son. McGinnis remembers her mental state after losing custody of her first child: “I just didn’t care about anything anymore.”

Still, she managed to get her GED while in prison. Her second incarceration came later when she and two other friends entered an abandoned building and stole $35 worth of tools. She was given a 13-month sentence based on being a repeat offender.

“You’re out of luck”

Art Rios, a member of the Civic Action Group at Sisters Of The Road Cafe, discussed his experiences in and out of prison. A native of Sacramento, Calif., his struggles to return to society after serving more than 4 years at San Quenton Penitentiary for stabbing a man included 16 years of homelessness.

Art is passionate about the lack of support for former prisoners, and, especially, the difficulty of coming back to a home that deems you undesirable.

“Unless you have family,” says Rios, “you’re out of luck.” For many criminals, says Rios, even family can be unforgiving.

Speaking bluntly about prison life, Rios unveiled the cyclical criminal patterns of his family.

“There was one year,” he recalled, “where I went to county (jail) 114 times.” When he served his first hard sentence, a six-month stint at Folsom Prison, he joined some of his family members who already were locked up. When he got out of Folsom, however, his remaining family refused to take him in.

Rios takes particular pride in the way California is dealing with the issue of homelessness. Specifically, he mentioned EDAR (Everyone Deserves a Roof), a Los Angeles initiative that provides cart-sized, collapsible shelters, as well as a recent effort in Sacramento, where 10-foot by 10-foot transitional housing units were being built — an attempt to ease prisoners out of living in tiny cells.

Once you’ve been in prison, society “sees you as a violent person with no remorse,” he says.

Transitioning out of prison life was especially difficult for Rios, a recovering addict who has been sober since 2006. Given that many of the resources available for ex-cons are dependent on clean urine samples, it’s no surprise that finding housing and employment is difficult. Post-prison, it took Rios two years to get back on his feet.

“I don’t want to be continually punished”

Even though they are free of the constraints of prison, both Gollyhorn and McGinnis find their lives in a state of flux. Gollyhorn has been evicted from his Hillsboro home and has been staying with McGinnis and Destiny while he waits for a room through Transitions Project Inc. For the first time in his life, he is focused and has plans on going to school for engineering.

His eyes light up when he talks about the possibilities for his future, but it’s the past that seems to solidify where he is at present. “I want my rights back,” he says, noting the extreme difficulties in finding work for a person like himself — someone, in particular, who has been legally designated a “kidnapper” based on one of the charges from his arrest. “I don’t want to be continually punished for a mistake I made.”

Rios spoke of how there should be better housing and drug treatment programs, but that, most importantly, there should be assistance with family reunification. Rios was a primary player in a homelessness protest last year and continues to make appearances at City Hall in the name of equal rights for the homeless and more resources for former prisoners. Ending the cycle of transitioning from prison to the streets and then back into prison will take an entire societal transformation, according to Rios, who said, “Change the attitude. Seriously.”

For all three, though, having a second chance at life is a crucial thing. It is family support, which for all of them includes the community of friends they have at places such as Sisters Of The Road that keeps them going. “If your family can’t look out for you," says Gollyhorn, “who’s gonna?”