Editor’s note: As part of Street Roots’ ongoing solutions-based reporting on the foster care system, Street Roots took a deep dive into the national and local data on placement stability and disruptions for young people in foster care. With funding and collaboration from the Solutions Journalism Network, Street Roots searched for positive deviants, or unique programs, showing evidence of success in reducing the number of moves for kids in foster care.

Read the parts one through four of the series here.

Sharon Annett’s eyes are now wide open to what’s really going on behind closed doors.

“I didn’t understand there are people out there mistreating children so badly,” said Sharon Annett. “It’s just horrific the stories you hear about what these little kids have been through.”

Sharon Annett is a treatment foster care parent, meaning she and her husband Jim Annett care for children with the most severe emotional and behavioral problems. The Annetts cared for more than 25 foster kids in the last 20 years.

“A lot of these kids are just misunderstood,” she said. “Adults have not taken the time to really figure them out.”

For decades, Sharon Annett provided foster care through Oregon Community Programs (OCP) in Eugene. If she’s learned anything as a foster parent, it’s that every child is different.

“We see potential in all the kids we take, so we try to tap into it and show them they are worthwhile,” Sharon Annett said.

OCP uses the evidence-based treatment model, Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO) to help stabilize youths in a homelike setting and then prepare them to return to their families.

Researchers at Oregon Social Learning Center (OSLC) in Eugene developed the TFCO model nearly 40 years ago, and it’s now well-known in child welfare circles across the United States and countries around the world, including Australia, Sweden and Norway.

The president of Treatment Foster Care Consultants, Inc., John Aarons, said it’s remarkable the TFCO treatment model spread around the world but still hasn’t caught on in its home state of Oregon, where it’s only offered in the Eugene-Springfield area.

“We’ve spent all this money on sending kids to these group homes where horrible stuff happened; probably not horribly intended, but it was a disaster,” said Aarons. “We need to do better than that.”

But Oregon’s hesitancy to invest in TFCO and other companies’ therapeutic foster care models appears to be decreasing.

Backed with a $2 million funding allotment from the Oregon Legislature, the Oregon Department of Human Services (ODHS) is launching a statewide pilot project to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of expanding treatment foster care in the state. TFCO is one of three treatment models to be implemented by care providers in the 18-month pilot project.

Led by Greater Oregon Behavioral Health, the seven providers in the pilot will treat children struggling with extreme behavioral and emotional needs. Each provider selected a model that best suits their agency. OCP was the only provider in the group to select TFCO, even though OCP already participated in a randomized trial of the TFCO model 20 years ago and continues to use it today.

ODHS anticipates the pilot project will lead to a gain of 59 available beds for kids by late 2023.

“Lessons learned through the pilot will be analyzed in consideration of a long-term strategy for a new permanent type of care,” said Sunny Petit, ODHS press secretary.

Petit mentioned, with results from the pilot, they’ll be looking at implementing the TFCO model on a larger scale in the future.

Evidence points to better outcomes for youth in some settings

Aarons said scientists from OSLC in Eugene developed the TFCO model in the early 1980s following extensive research. In 2002, a group from OSLC created Treatment Foster Care Consultants, Inc. and paired up with OCP to implement the model in a real-world setting.

For 20 years, Oregon Community Programs (OCP) in Eugene has been the first, and only, agency to provide the TFCO model in Oregon. OCP recruited foster families and treated kids using TFCO as researchers conducted randomized trials of the model.

“We needed to demonstrate it could be implemented on a practical basis, not just theoretical basis,” said Ana Day, OCP’s executive director, who oversees three teams running the model in the Eugene-Springfield area.

Aarons said randomized control trials confirmed agencies using this team-supported model in a foster home setting can help prevent the escalation of delinquent or violent behavior in youths, decrease the rate of teen pregnancies and encourage better academic engagement.

“When you look down the road, the youth are so much less likely to struggle with relationships, employment, school and when they have kids of their own,” Aarons said.

For example, Aarons said researchers followed the long-term progress of a group of young women who experienced treatment with the TFCO model as adolescents. Nearly nine years of data showed the 41 women had fewer criminal convictions and a reduced rate of ongoing child welfare involvement as adults, when compared to 44 young women who received treatment as usual in group care.

Structure, routines and the power of positive reinforcement

Annett has seen firsthand the importance of having biological families, guardians or adoptive parents continue to uphold the same structures and routines that the kids are taught in the TFCO model.

She said one of her family’s biggest disappointments with fostering involved a boy who did well in their home and moved on to a pre-adoptive family.

“I wrote books on his routine, what worked and what didn’t work for him, and everything he needed,” Annett said. “I spent hours on the phone with this family.”

She said after 10 months, the family returned the boy.

When another adoptive family eventually came along, Annett said the same thing happened.

“After three weeks, this kid got sent back because they didn’t do what I told them to do,” she said. “It’s frustrating to see all of your work crumble into little pieces, and it’s not the kid’s fault. The adults in their life have let them down.”

Annett said the boy never found a forever family. He aged out of foster care on his own.

Many youths who participate in the TFCO treatment model experienced more than 10 placement disruptions during their time in foster care, including multiple stints at group treatment homes and psychiatric institutions.

Day said recruiting the right type of foster families is a crucial first step for the TFCO model to succeed. The teams need foster families willing to take in a single, high-needs child for about nine months — and then do it again with the next child.

“We’re looking to build professional foster parents,” Day said.

The Annetts say they are well-known in their small town outside of Eugene for providing care to a constant stream of kids in need. Sharon Annett said she makes sure all youths understand they’re not staying long.

“We came into this with the mindset: this is a job,” Sharon Annett said. “We’re going to wrap our family around this child and love them to pieces; give them support and structure; let them know they’re worth it, and then find a better place for them.”

TFCO consultants say matching kids to appropriate treatment foster families is one of the keys to the model’s success.

“We want kids to be placed with families that look like them and talk like them, and have language skills like them,” Aarons said. “We want to embed in the community.”

Each team under the TFCO model has a leader who oversees up to ten foster families. The team leader coordinates support services with a recruiter, youth skills trainer, youth therapist, family therapist and foster parent advisor.

The team encourages foster parents to provide constant supervision and steer the child away from problem peers. The parents learn to emphasize school work and tackle challenges with positive reinforcements.

“So many of the kids who come into this level of care have experienced a history of a thousand defeats,” Day said. “They’ve heard a lot about they’re not doing well, and they’ve been in trouble in a lot of places.

“So, we have systems that are evidence-based and well-established to make sure they’re getting credit throughout the day for the things they’re doing well.”

While the young people receive positive reinforcement from their foster families and therapist, team members simultaneously work with the children’s families or guardians to develop effective parenting and coping skills. They want families to be ready to take over care when the youths graduate from treatment.

Child welfare group in Illinois expands TFCO model

Lutheran Social Services of Illinois (LSSI,) the state’s largest private child welfare organization, expanded its use of the TFCO treatment model (which it calls treatment foster care) as it completed a five-year pilot project in Illinois in June 2021. LSSI has teams operating in Chicago, Aurora and Rockford, Illinois. LSSI hopes to add another in Peoria, Illinois.

Anne Barclay, who facilitates the model for LSSI, said state child welfare leaders wanted to find an alternative to residential care for foster youth following a searing investigation by the Chicago Tribune which exposed allegations of abuse and neglect at state-contracted group care facilities.

As Street Roots reported in 2019, a similar controversy is playing out in Oregon. Nonprofit groups A Better Childhood and Disability Rights Oregon, and their partners, are suing Oregon on behalf of foster children and demanding a total overhaul of the state’s foster care system.

LSSI selected TFCO for a five-year pilot project involving three teams of kids from 6 to 11 years old. TFCO team leaders and foster families began accepting kids into homes in 2016 and have never looked back.

Barclay said the pilot program was so successful, child welfare leaders elected to continue treatment foster care in the state and even added an additional team in Chicago last year. She said the TFCO model is helping get significantly challenged kids back home with their biological families or other caregivers in Illinois.

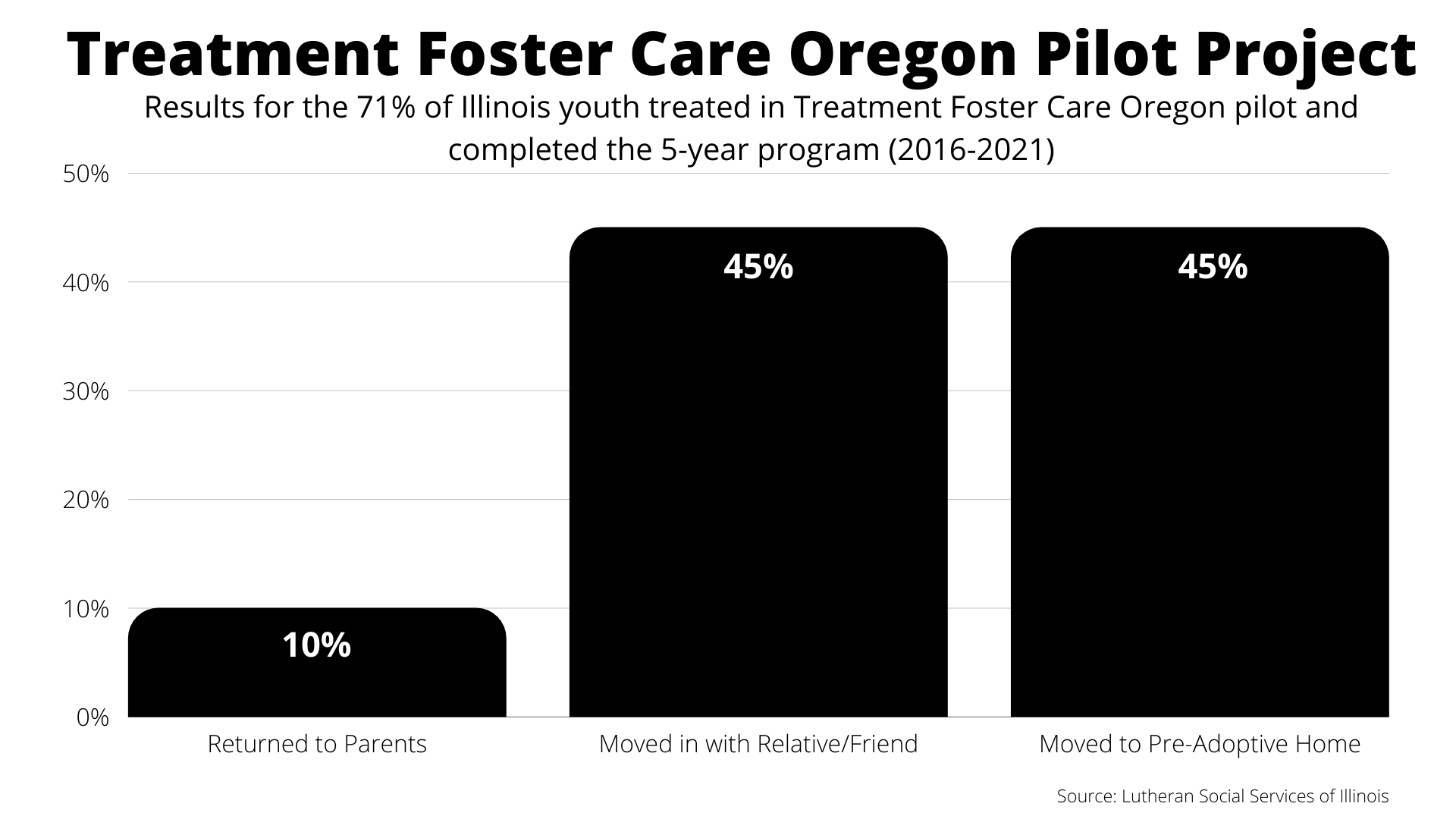

“We found 71% of kids who came into Treatment Foster Care completed the program and were able to step down to their prepared aftercare home,” she said, referring to results from the pilot project using the TFCO model.

Barclay said 10% of the youth who graduated from treatment were able to return to their parents. Another 45% moved in with a relative or known family friend. The final 45% were placed with specially selected, pre-adoptive foster families.

The waiting list for treatment foster care in Illinois has grown to about 10 to 15 youths at any given time for the teams’ 40 slots — which will increase to 50 if LSSI is able to fund the additional team in Peoria, Illinois.

Along with its success, Barclay said the LSSI pilot project was met with some initial pushback by group care providers in Illinois who see the TFCO model and other therapeutic foster care models as direct competition. Also, many child welfare workers were skeptical treatment foster care families could handle youths with such extreme behavioral challenges.

“Some of the kids we took did overwhelm our foster parents, and some overwhelmed the staff,” Barclay said.

Teams overseeing the foster homes determined the TFCO model worked best for kids who had family or another caregiver awaiting their return, making the youth more invested in their treatment.

The teams also faced challenges recruiting additional foster families and team members in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Quarantining impeded word-of-mouth recruiting during lunches or other social gatherings with current foster families.

Barclay said many of their teams are running well under capacity. One team in Rockford, Illinois, only has one foster family serving a single youth; but Barclay said four foster families are currently “in the hopper.”

Even foster families already serving kids are cautious about opening their homes to new youths and multiple team members due to COVID-19 safety concerns.

Recruiting is also a concern in Oregon where Child Welfare has struggled for years to convince people to step forward to serve as foster parents, even for regular foster care.

Aarons said for the TFCO model to expand around the state, Oregon needs more than just foster parents. He said child welfare, mental health services and the juvenile justice department all need to be convinced it’s worth the long-term investment.

He said an analysis from the Washington Institute for Public Policy shows “for every dollar invested in Treatment Foster Care Oregon, there are four dollars saved.”

Day said she’d like to see the TFCO model expanded beyond Lane County so kids wouldn’t have to travel across the state to receive care in the Eugene-Springfield area. She said the state could quadruple the number of treatment foster homes in Oregon, and there would still be kids to fill the beds.

“I’ve seen kids who no one thought were ever going to be able to, go home ... with their mom,” Day said. “That was powerful for me. It’s just setting them up for success and shifting the trajectory, so they really have a chance.”

The Annetts have also experienced many successes. The father of a little girl they cared for when she was 4 years old invited the couple to her 8th-grade graduation. A set of boys they fostered at 4 and 5 years old are now finishing high school. Even a 10-year-old boy who refused to follow the treatment model came back to visit the Annetts 10 years later.

“He thanked us,” Sharon Annett said. “He said it was the best place he ever lived, and he was sorry he didn’t make it work.”

He has since founded a nonprofit to help other children in foster care.

Sharon Annett tells prospective foster and adoptive parents, “You have this idea in your head about how it’s going to be, but it’s not going to be like anything you’ve ever experienced.”

She said it’s never easy to find families willing to stand by these kids.

“We want to make sure the next place they go after us is the final spot.”